Can’t sell it, can’t borrow against it, can’t develop it

The poverty rate among Native Americans is more than twice the national average and the highest unemployment rate in the U.S. is on reservations. A dearth of well-paid jobs, the remote location of many reservations and inadequate health care all weigh against economic advancement.

Another big obstacle, long recognized but which has to date received little rigorous statistical analysis, is the byzantine way land is titled on the reservations of many of the country’s more than 500 federally recognized tribes. Native Americans have large amounts of land that they can’t borrow against, sell or develop. Imagine you couldn’t inherit the home your parents built or pass your property along to your children. Or tap the equity in your home to add a new kitchen, send your child to college or start a new business.

This is a huge impediment to wealth creation on reservations: In America, primary residences account for 62% of a median homeowner’s total assets and 42% of their wealth, according to the National Association of Homebuilders. Some 72% of white households own their home, but just 55% of Native American and Alaska Native households do, according to Prosperity Now, a Washington, D.C., nonprofit focused on helping low-income families build wealth.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

A working paper by UCLA Anderson’s Christian Dippel, Vassar’s Dustin Frye and Arizona State University’s Bryan Leonard provides a causal estimate of the consequences of these land tenure policies on land utilization and values. Their findings suggest that Native American households are missing out on billions of dollars (in land wealth) because they lack the basic property rights that are critical to development and that are central to most Americans’ wealth.

The roots of the land tenure problem lie in the ill-conceived implementation of historical policies designed to assimilate Native Americans into mainstream society by way of individual land ownership. From 1887, President Grover Cleveland redistributed nearly 41 million acres of tribally owned land to individual tribal members through individual allotments, with the intention of breaking up the reservations and weakening tribal control.

Local BIA Agent Holds Sway

When the federal government “allotted” land titles to individuals, a patent was issued to individuals “in trust.” This allotment could later be transferred to fee simple (full property rights) at the discretion of the local Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) agent. Study co-author Frye is an enrolled member of the Northern Cheyenne tribe, and his grandmother was one of the original allottees. Her allotment was never transferred to fee simple.

Nearly a half century later, in 1934, the federal government abandoned the controversial “allotment” program, leaving the tribes with a checkerboard of tribal lands, allotments held by individual “allotted trust” (under government control) and allotments held by individuals in fee simple.

This checkerboard persists almost unchanged to the present day. Individuals holding trust land can work and use the property but can’t sell and can’t develop it without the approval of the BIA. Since the federal government holds the title to trust land, banks won’t accept it as collateral for loans.

Furthermore, historically, when the owners of trust land died, it was passed to all heirs in “equal undivided interest,” leading to increasingly fractionated ownership. Today, owners of trust land can write wills to prevent fractionation, but in many cases it is too late because ownership fractionation has already occurred, explained Dippel in an interview. He cited one example from a 1987 Supreme Court case involving a 40-acre tract on the Sisseton-Wahpeton Lake Traverse Sioux Reservation in South Dakota. That piece of land, which produced $1,080 in annual income at the time of the ruling, was valued at $8,000. It had 439 owners, one-third of whom received less than 5 cents in annual rent and two-thirds of whom received less than $1. The largest interest holder received less than $82.85 per year, according to court filings. This fractionation of property is a big barrier to development on reservation land, as it introduces huge transaction costs to any productive use of the land.

Satellite Images Reveal Land Use Patterns

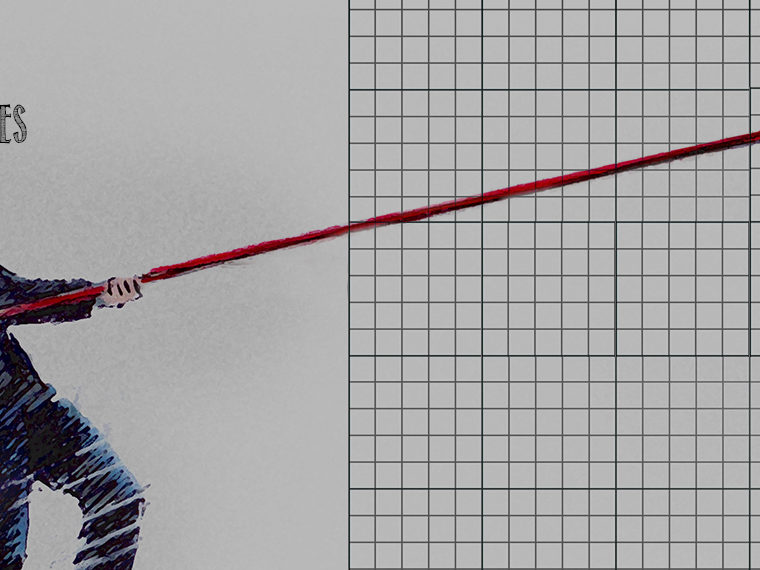

To estimate the economic burden of those transaction costs and of the inability to collateralize land wealth, the researchers used the federal government’s Public Land Survey System (PLSS) to match up specific allotments with Bureau of Land Management (BLM) data that included the owner’s name, the date of an allotment’s issuance and its acreage and geolocation. This was then matched to fine-grained satellite imagery on land utilization. That allowed them to compare the levels of development and cultivation on parcels with full fee-simple property rights with trust parcels that have only use rights, controlling for differences in land quality, elevation and access to water. (The spliced together photos atop this article show, to the left, fee simple land and, to the right, trust-held land.)

To get an apples-to-apples comparison, the researchers leveraged their fine-grained satellite data to home in on comparing land plots under different legal tenures within successively smaller neighborhoods, all the way down to one square mile. The detailed work aims at moving beyond mere correlation to the land policies and actually estimating economic impact caused by the policies.

To get an even better claim to a causal estimate, the authors pursued an instrumental variable (IV) strategy, in which they used the original allottees’ age as well as the identity of the BIA agents in charge of different allotments to explain whether an allotment stayed in trust or was transferred to fee simple. The logic of this is that allottees who had not come of age by 1934 (when the policy ended) were never eligible for transfer to fee simple, and that different individual agents working for the BIA had very different estimated inclinations toward transferring land to fee simple.

Using these techniques, the authors found that reservation lands owned under full property rights have 20% more development and 35% more cultivated acreage than similar lands held in government trust. (Development, in this case, can mean anything from a casino to a barn or simply a family home.)

56 Million Acres

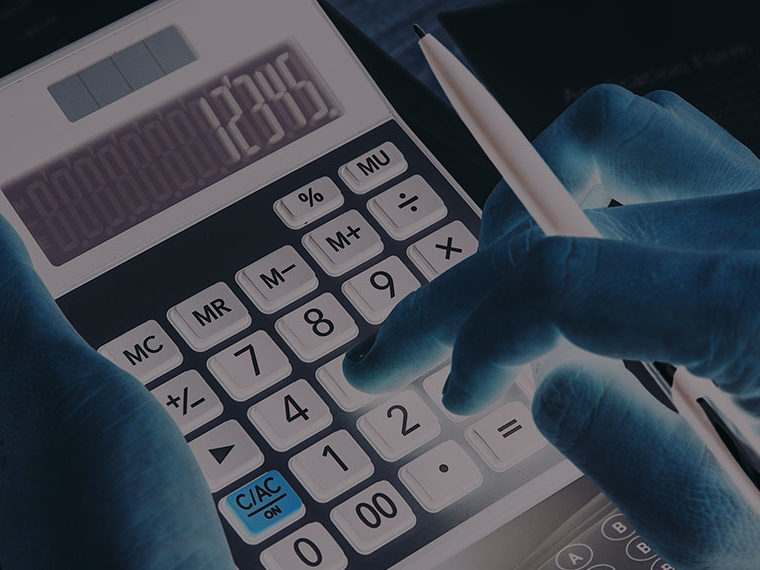

The authors did a “back of the envelope” calculation comparing land with or without full property rights on reservations in Montana, Utah and Washington state (where county assessor data was available). Using assessors’ data for comparable land near the reservations, they estimated that having full property rights would add between $4,000 and $15,000 in value to an acre of land, depending on land prices surrounding a reservation. This amounts to between $500,000 and $1.8 million per 160-acre allotment.

With about 56 million acres of reservation land held in trust by the federal government, that translates into hundreds of billions of dollars in “lost wealth” for tribal members who hold their land without full property rights.

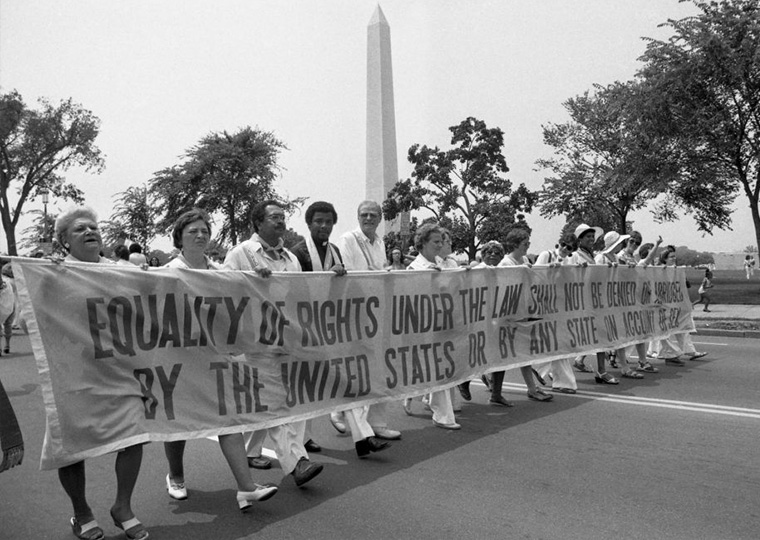

At a time when the Black Lives Matter protests have revived the debate over reparations for African Americans, these findings serve as a reminder of the historical plight of America’s original indigenous populations.

There is, in fact, a deep connection between the study of trust land on reservations, and the reparations debate for Black Americans: The twin problems of fractionated ownership and an inability to collateralize land wealth are shared not only by many indigenous communities throughout the world but are also a major concern in the rural South, where a large proportion of African-American-owned land is tied up in so-called heirs’ property.

Although their historical origins differ, heirs’ property and reservation trust lands both suffer from high transaction costs because of the “fractionated claims” and inability to collateralize, explained Dippel. This has contributed to poor landowners’ losing their property through contested claims of ownership, forced sales and fraud.

A Clue to Black Americans’ Lost Property Value

By providing an estimate of the economic loss arising from the legal impediments on reservation trust land, this study indirectly also provides an approximate estimate of the cost of heirs’ property to Black Americans.

Dippel explained in the interview that legal initiatives are underway to solve both the problem of heirs’ property and trust land. One such effort is the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act, which makes it more difficult to force the sale of property with multiple claimants or acquire the land in a secret sale or at a below-market price. The act, a project of the American Bar Association, has been adopted by 14 states.

Tribal leaders are divided on the benefits of transferring trust land to fee-simple title, because fee-simple land can subsequently be sold to non-tribal members. This carries with it the potential of eroding a tribe’s land base, which naturally raises alarms for tribes that have already lost vast amounts of their territory, which was stolen or lost to speculators or sold off to non-Indians throughout history.

Dippel agreed that while full property rights is “clearly (the) most efficient” form of land ownership and offers the best economic value, tribes also worry about protecting and extending their culture and sovereignty, and returning trust land to tribal control may therefore be a preferred solution for some tribes. But according to Dippel, there is no question that either fee-simple rights or tribal control is “better than the current status quo of having the Bureau of Indian Affairs paternalistically administer it as trust land.”

Fortunately, there is a successful template for indigenous communities in terms of striking a balance between efficiency-maximizing individual property rights and culture-preserving communal rights. Between 1993 and 2006, the Mexican government implemented a massive land reform program known as Procede, which granted indigenous farmers full title to land they had cultivated since the 1930s. But it was the communities themselves, known as ejidos, that decided whether those rights were only transferable within their borders or whether the land could also be given or sold to non-community members. Studies by Alain de Janvry of UC Berkeley and others credit Procede with providing measurable improvements in wealth and economic security for some of Mexico’s poorest farmers.

Featured Faculty

-

Christian Dippel

Assistant Professor of Economics

About the Research

Dippel, C., Frye, D., & Leonard, B. (2020). Property rights without transfer rights: A study of Indian land allotment.