How 934 workers around the globe regard their labor; it doesn’t have to be this way

It is an unwritten rule that any mention of artificial intelligence these days must include the adjective transformative. Open-spigot spending to establish a dominant foothold in this technological capability speaks to its potential to cause a seismic global economic shift.

IDC, a tech-centric research and consulting firm, estimates that the current $235 billion in global AI capital spending will reach more than $630 billion by 2028. A recent Goldman Sachs report expects AI-related annual capital spending to reach more than $1 trillion in the next decade.

The big four tech platforms — Meta, Alphabet, Amazon and Microsoft (a major investor in AI first mover OpenAI, which was recently valued at more than $150 billion) — shelled out a combined $190 billion on capital spending in the 12 months through June, according to the Wall Street Journal, compared with $110 billion for the 12 months through June 2020.

Pulling off the AI revolution requires a whole lot of money to buy the chips capable of processing the advanced tasks demanded by the technology, build more data centers to house all that new data, and purchase mind boggling amounts of electricity to run the algorithms that can automate basic data-centric tasks previously reliant on humans (first-generation traditional AI), as well as perform more complex creative thinking/reasoning (generative AI).

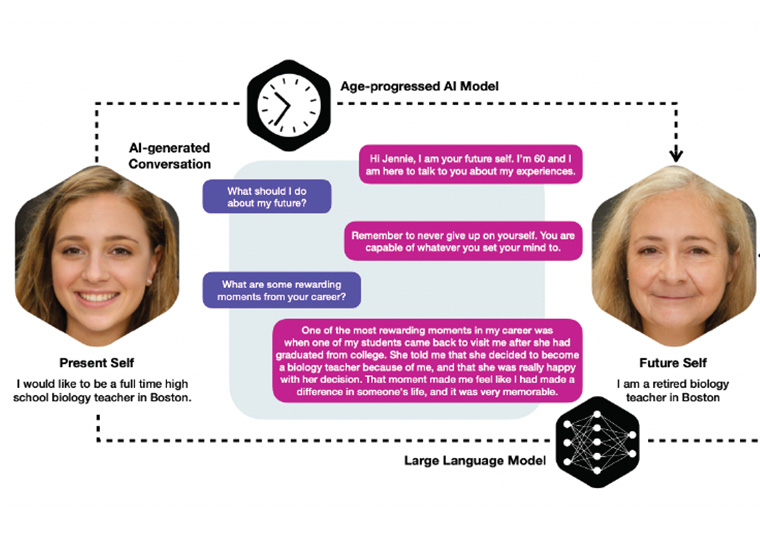

(For the less AI-attuned reader: Traditional AI processes existing data to make predictions. Those “recommended for you” movies and shows on streaming services are classic AI. Generative AI harnesses data to create something entirely new, be it written, spoken or video. If you’ve used apps such as ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, Jasper, Midjourney you’re already a card-carrying member of the generative AI ecosystem.)

Human Capital Makes the AI Go Round

This massive technological advance has rightfully sparked great debate on its potential long-term impact on displacing workers. What’s getting far less attention is the fact that the current state of the AI economy relies on a tremendous amount of human capital.

While it’s a good time to be a cutting-edge AI research scientist or engineer, those highly compensated tech jobs often are dependent on a global army of millions of workers who do the unglamorous work of collecting, cleaning up, annotating and labeling data that is the lifeblood of fancy algorithms.

An AI algorithm or tool needs to be told a chair is a chair, a red light is red, a field of corn is a field of corn. A tumor is a tumor. Text and images must be cleaned up and vetted for accuracy and scrubbed of anything violent or inappropriate. An image may need to be manually highlighted so the AI technology knows where to look for its data point.

“To endow a self-driving car with human-like vision, the AI must be fed millions of images, each labeled with its contents (e.g., pedestrians, stop signs, cyclists). Labeled images can help AI detect potential cancer from diagnostic scans, and voice activated AI assistants such as Amazon’s Alexa can recognize human speech thanks to troves of human-transcribed audio clips. These vast quantities of labeled training data assembled through brute force by human workers provide the “ground truth” from which AI algorithms learn.”

For all its 21st century technological wizardry, AI relies on a digitized supply chain of workers doing basic, invisible work that makes the magic possible. And after an AI app or system is built, more humans are needed to perform quality assurance that both the tool and its underlying data are good to go to market and to continually update the system as new or better data become available.

These so-called ghost workers scrubbing, prepping and reviewing data for the AI economy, and testing algorithms before they are unleashed on the marketplace, are a bit like the field worker picking crops that land at the grocery or restaurant, or the worker on a garment assembly line supplying the fast fashion industry.

A TIME investigation last year reported that workers in Kenya were typically paid less than $2 per hour to scrub offensive content from text to be used in Open AI’s ChatGPT tool. The workers were employed by a third-party firm, Sama, based in San Francisco that employs digital workers in Kenya, Uganda and India.

A letter sent by eight Democratic members of Congress last year to major AI players including the CEOs of Alphabet, Amazon, IBM, Meta, Microsoft, Open AI and Anthropic, laid out “deep concerns” about the working conditions of this upstream network of digital crowdworkers.

“Millions of data workers around the world perform these stressful tasks under constant surveillance, with low wages and no benefits. These conditions not only harm the workers, they also risk the quality of the AI systems — potentially undermining accuracy, introducing bias and jeopardizing data protection,” the legislators wrote. The letter referenced an estimated $1.77 median hourly wage on Mechanical Turk, or MTurk, a popular crowdsourcing marketplace.

While the continuing evolution of AI may replace some of this human labor, the current thinking is that there will still be a significant need for human involvement in processing the data building blocks that AI runs on; AI learning from earlier produced AI-is already raising concerns among some researchers about generic and biased content. Yet the potential abuse of upstream ghost workers — and for that matter how such mistreatment may impair the quality of the downstream algorithms — has yet to translate into any legislative or regulatory correctives.

How Ghost Workers See Their Jobs

Results from a survey of more than 900 crowdsourcing workers on MTurk, forthcoming in Business Horizons, provides insights into how ghost workers themselves size up their work situation.

UCLA Anderson’s Auyon Siddiq, Charles J. Corbett and Martin Gonzalez-Cabello, a Ph.D. student, and Catherine Hu, a UCLA graduate, asked a series of questions to tease out the nitty-gritty of AI ghost work. This included tracking how much time workers spent looking for assignments (a common construct is for employers to publish jobs and pay rates on platforms that workers vie for). The researchers also asked participants the proportion of work they regretted accepting, how often they were allowed to take breaks from their computer work, how engaging the tasks were and how fairly they felt a given platform treated them. The study did not aim to get input from a representative sample of workers on different platforms, but to reach workers active on multiple platforms. Participants named 20 other platforms in addition to MTurk.

More than half the survey participants had a bachelor’s degree, and nearly two-thirds were male. About 60% of participants did this ghost work as a complement to other work, suggesting a gig-worker structure along the lines of picking up some ride-share income on the side. These workers are essentially part-timers, as opposed to full-timers who depend on ghost work for their income. The geographic distribution was pretty much evenly distributed into three buckets: the United States, India and the rest of the world.

One in five participants rated MTurk as “somewhat unfair” or “very unfair.” A lack of meaningful work may be part of the problem. Participants who reported their work was somewhat or very boring were six times more likely to say the platform was unfair compared with participants who reported more engagement with their tasks.

Not surprisingly, the (unpaid) time spent looking for work on a platform is strongly associated with satisfaction. Participants who said they spend more than 30% of their time looking for a gig had a much higher sense of unfairness compared with those who spent less than 30% of their time hunting around.

Despite full-time workers reporting they needed to spend more time on MTurk looking for work (relative to part-timers on the platform), having less break time and feeling more obligated to accept tasks, the full-timers rated the platform more fair than the part-timers.

“This may be due to alternative employment opportunities being worse or nonexistent. Our finding is consistent with the concern that workers who are reliant on crowd work might tolerate even worse working conditions and be prone to exploitation,” the researchers write. Although gig work is often touted as particularly beneficial to the socioeconomically disadvantaged, this suggests the opposite is true: Part-timers, who have more alternative opportunities, can enjoy the flexibility of gig work, but those with no other options have to put up with whatever comes their way.

Not All Ghost Work Is Created Equal

A subset of 165 respondents also worked on the Prolific platform, which was rated as significantly more fair than any other platform.

Given the high rating for Prolific, the researchers explored how that platform compares to the goliath MTurk.

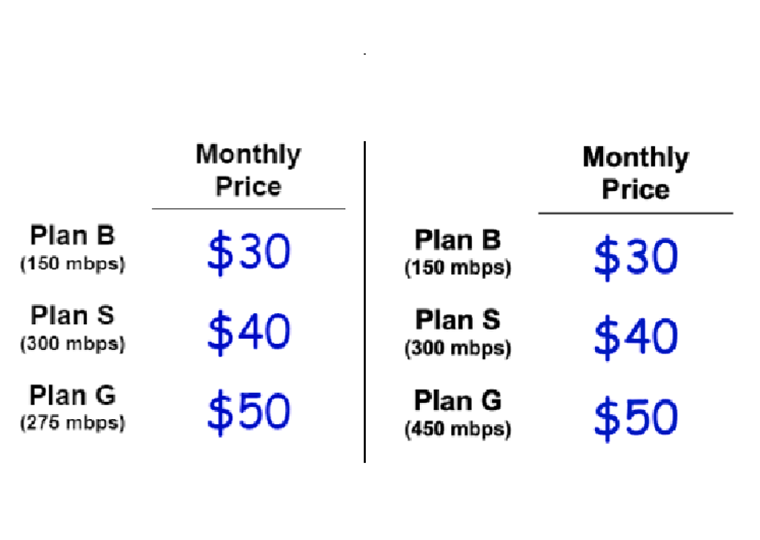

The Prolific model is far smaller by design. It vets potential workers and aims to keep its pool of potential workers in line with its universe of job listings. (MTurk is more a supply-demand free-for-all; any vetting is done by the paying customer.)

For those who can squeeze past those constraints there’s a far better payout. Prolific demands that employers pay a minimum wage of at least $8 an hour; that’s far more than MTurk, which does not get involved with pay rates. Moreover, Prolific funnels more job opportunities to vetted workers who have completed fewer tasks, effectively reducing the time needed for workers to search for work.

Overall, Prolific was deemed a fairer deal than MTurk.

That suggests stakeholders looking to improve the AI ghost work ecosystem could learn a bit from the Prolific model. Moreover, the researchers suggest there may be some learning to be had by studying the world of old-school physical supply chain management. They cite Nike’s hard-earned lesson from the 1990s when it was criticized for relying on sweatshop labor, but initially tried to duck responsibility by pointing out it didn’t own the factories exploiting workers. After much public backlash, Nike leaned into more accountability for work conditions along its supply chain.

Audits are another opportunity for stakeholders in the ghost worker economy. Formal third-party auditing of crowdworking conditions seems like it would be in sync with the “S” part of ESG initiatives.

And more consideration of fair workplace practices just might be good business. As the researchers explain, Prolific appears to produce superior data quality while treating its workers more fairly. “Given that AI relies critically on the accuracy of training data, investing in the well-being of crowd workers could yield better AI technology in the long run,” they write.

Featured Faculty

-

Auyon Siddiq

Assistant Professor of Decisions, Operations and Technology Management

-

Charles J. Corbett

Professor of Operations Management and Sustainability; IBM Chair in Management

-

Martin Gonzalez-Cabello

Decisions, Operations and Technology Management, Ph.D. candidate

-

Catherine Hu

UCLA graduate

About the Research

Gonzalez-Cabello M., Siddiq A., Corbett C.J. & Hu C. (2024). Fairness in crowdwork: Making the human AI supply chain more humane, Business Horizons.