Research tracking Florida siblings helps isolate the impact

U.S.-born students with high exposure to immigrants in their schools scored better on math and reading tests than similar students with low exposure to immigrants, a working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research finds. What’s more, economically disadvantaged and black students received the greatest boost from studying alongside immigrant peers, enjoying a bump in performance twice as large as other native-born students.

Positive factors immigrants bring to school include being relatively better behaved, and thus less disruptive and, in some cases, being academically advanced relative to their U.S.-born classmates.

The study seeks to untangle the impact of the presence of immigrant students on U.S.-born students from statistical factors that have complicated study of the topic to date. Among these are the tendency of some white families to flee schools with high immigrant enrollments; the vastly different levels of English language capability, parental education and economic status found in both immigrant and native populations in the U.S.; and the perception that immigrants exert a negative influence on their classmates fed by the fact that non-U.S.-born students often concentrate in schools with overall lower test scores.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

The working paper, by Northwestern’s David Figlio, UCLA Anderson’s Paola Giuliano, Riccardo Marchingiglio, an economist with the Analysis Group, Umut Özek, principal researcher at the American Institute for Research, and Northwestern’s Paola Sapienza, tries to screen out those complicating factors.

The paper relies on a dataset from Florida that links population-level school records and birth records. This allowed the researchers to focus on siblings who shared the same family characteristics (i.e., parents, economic status, access to teaching support) but who had different levels of exposure to immigrants in their schools. The paper further restricted the sample to U.S.-born students who spoke English at home.

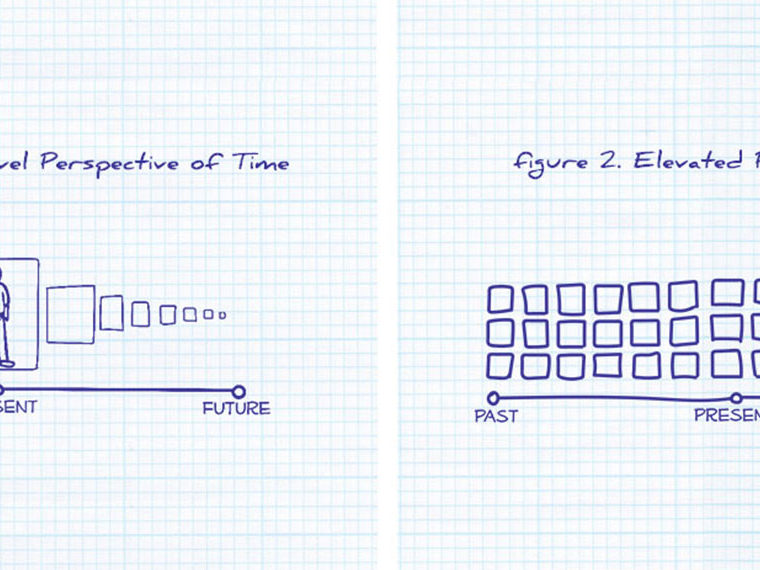

By tracking these sibling sets over time, starting with kindergarten, the researchers were able to link educational performance with the students’ cumulative exposure to immigrants. Interestingly enough, when they looked at all students, they found a “significant — although small in magnitude — negative correlation” between the share of immigrants and the math and reading test scores of their native-born peers. But when they zeroed in on siblings, that relationship between exposure to immigrants and academic performance turned positive. The U.S.-born students with a higher cumulative exposure to immigrants scored better on math and reading tests.

The researchers attribute the differing results to the white flight phenomenon, in which white and affluent students with higher scores leave schools with high immigrant concentrations. By focusing on sibling pairs, the study was able to prevent the school selection problem from skewing their results.

Maternal education is an important predictor of educational performance. In this study, the difference in test scores between students with the highest cumulative exposure to immigrants (90th percentile) and those with the lowest cumulative exposure (10th percentile) corresponded to a significant difference in scores between children whose mother had a high school diploma and children whose mother had not completed high school. In other words, a child who had more immigrant classmates enjoyed an educational boost similar to a child who had a better-educated mother.

Exposure to immigrants was positive for high- and low-performing students, according to the findings. “Remarkably, immigrant students do not negatively affect U.S.-born students, even when (the immigrants’) academic achievement is relatively lower (than their U.S.-born classmates),” according to the study.

In 2015, almost 1 in 4 public school students in the U.S. came from an immigrant household; in some school districts in Texas and Florida immigrants represented more than 70% of the public school population.

Perceptions of the immigrant students’ impact are easily conflated with one’s views on immigration itself. Proponents believe foreign-born students enrich the learning experience by bringing their diverse cultures to the classroom. Critics argue they demand a disproportionate share of resources, hurting the educational performance of U.S.-born children.

One possible explanation for the positive impact, UCLA Anderson’s Giuliano explains in an email exchange, is the “behavioral channel.” Immigrant students, on average, are disciplined less frequently than native-born students, according to the data. Using disciplinary records as a measure of behavior, they found exposure to better-behaved immigrants had a small, but positive effect on academic outcomes of their peers. This suggests U.S.-born students, particularly less advantaged students, might benefit by being exposed to these better-behaved students and being taught in a classroom with fewer disruptions.

Another possible explanation, Giuliano says, is the “relative standing channel,” which suggests the test scores of economically disadvantaged students or black students “improve because they are exposed to immigrants who perform better academically.”

In what ways might the learning environment influence these outcomes? To test this, the researchers compared the educational outcomes in schools where immigrants were more likely to be segregated into special classes, such as remedial English, and schools where immigrants were integrated into regular classes. They found that the test scores of the U.S.-born students were higher in the latter case, providing policymakers with evidence that all students might benefit from integrated classrooms.

Featured Faculty

-

Paola Giuliano

Professor of Economics; Chauncey J. Medberry Chair in Management

About the Research

Figlio, D., Giuliano, P., Marchingiglio, R., Özek, U. and Sapienza, P. (2021). Diversity in schools: immigrants and the educational performance of U.S. born students.