A growing body of research questions the value of the nod, eye contact, ‘mm-hmm’ and ‘uh-huh’

You’re speaking. The person you’re speaking to is giving a signal that they’re listening: looking you in the eye, nodding agreement, a knowing smile, interjecting an “mm-hmm” or “uh-huh.”

Success! You’re being heard.

Maybe not. A burgeoning area of study, with papers co-authored by UCLA Anderson’s Hanne K. Collins, is establishing that speakers who feel heard often are not; that when the spoken-to feign attentiveness, it’s highly effective at misleading a speaker; and that a more active listening mode — volleying back a bit of what you’ve heard, explicitly stating a desire to engage, especially on topics of a sensitive nature – is the path to a more effective sort of conversing.

And in this talky, message-crammed and disputatious world, the stakes are high. Collins and co-authors note: “Conversational listening is a key building block of human social functioning. Information transmission, interpersonal connection, conflict management, happiness — the key foundations of human flourishing — hinge critically on our ability to hear, understand and respond to others.”

A lot of prior research on listening zeroed in on whether the speaker felt heard. Technological advances have led to a more recent direction of study — observing, manipulating and transcribing hundreds of conversations, often on Zoom —which allows researchers to measure in real time both the feeling of being heard and whether someone is actually paying attention. And the result is a powerful listening gap.

The work has led Collins to suggest a remedy to improve the quality of interactions and, thus, of our relationships. “Counterintuitively,” she writes in a review of listening research published in Current Opinion in Psychology, “the very best listening is spoken.” Gestures and “back-channel” utterances (“mm‑hmm”) have a place, but to ensure high-quality listening, Collins says listeners should volley back verbal responses that incorporate some of what they have just heard or read (via text threads, emails, phone calls, etc.).

From Therapy-Speak to Business-Speak

The modern‑day reliance on physical (nodding) and paralinguistic cues (“uh-huh”) to signal listening evolved from ideas introduced in the mid‑20th century by psychologists Carl Rogers and Richard Farson. What came to be known as humanistic psychology encouraged therapists to practice “active listening” that strove to create a nonjudgmental and empathetic space. Physical cues such as nodding, smiling and paraphrasing were encouraged to telegraph attentiveness.

Beginning in the 1970s, a student of Rogers at the University of Chicago, Tom Gordon, wrote bestsellers that introduced active listening as a tool for parents, teachers, and business leaders. Gordon also highlighted the use of nonverbal gestures to signal listening.

By the late 20th century, listening was established as a core business competency in influential books such as In Search of Excellence and The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, and the seminars and training modules they inspired.

Yet what constitutes actual quality listening had not been so thoroughly researched. For decades, most studies explored whether speakers felt heard, often cataloguing their perception of the many nonverbal and paralinguistic cues those spoken-to use to convey their attentiveness. “Are they looking at me?” “Are they nodding?” “Are they leaning forward?” But there has been far less work on whether those cues in fact correlate to actual comprehension.

As early as 1988, linguist Wolfram Bublitz cautioned that habitual back channels like “yeah” and “uh-huh” can be “perfect devices for pretending to listen.”

In a paper published in Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, Collins, Harvard’s Julia Minson, Columbia’s Ariella Kristal and Harvard’s Alison Wood Brooks came along and, across five experiments, upended the utility of nonverbal cues. “It appears that people can (and do) divide their attention during conversation and successfully feign attentiveness,” they write. As a result, speakers often mistakenly feel they are being heard when they aren’t.

This listening gap can have a consequential impact on relationships, as the chasm between feeling heard and actually being heard is where arguments, frustration and disappointment can germinate.

A key feature of this research is its use of Zoom to capture a 360‑degree, real‑time view of what listeners and speakers experience during a live conversation. While past research often relied on third‑party observations or after‑the‑fact debriefs of experiment participants for their feelings about how well they were listening or how well they perceived they were heard, these experiments were able to capture, measure — and manipulate — the experience of both communicator and assigned listener simultaneously, in real time during naturally unfolding conversations.

Wandering Minds, Undetected

Collins, Minson, Kristal and Wood Brooks establish a baseline case that speakers tend to over-assume they are being heard. Two hundred participants were paired off for 25-minute Zoom chats; both parties privately reported at five-minute intervals whether they were listening or whether they thought their partner was listening.

Overall, speakers had a 70% success rate in correctly reading if they were being listened to or not; leaving a substantial 30% of interactions in which speakers read the room wrong. Moreover, in the subset of instances where the listener copped to having a wandering mind, nearly 80% of their speaking partners were simultaneously reporting they felt heard.

The researchers separately paired off 302 participants for five-minute in-person conversations that were also recorded.

The conversations occurred in a room in which commercial videos played on a screen. One participant had their back to the screen, while the other participant was assigned a specific listening condition: Some were instructed to be fully attentive, another subset was told to focus intently on the commercials playing on the video, and a third group was told to be “feigned listeners” who were to watch the videos while doing their best to pretend they were listening.

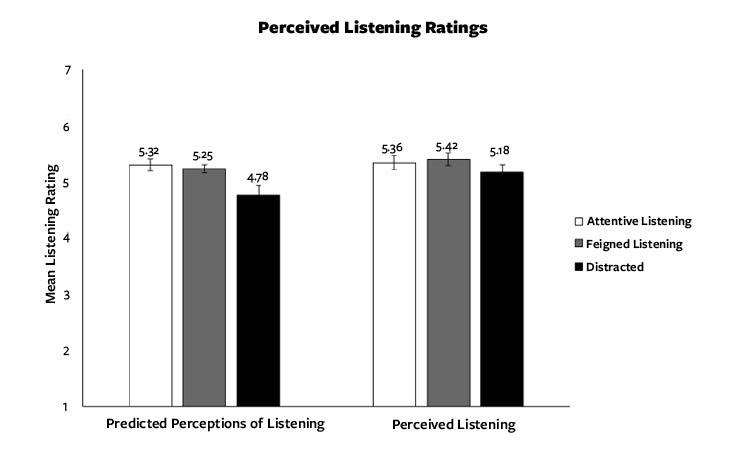

After the five-minute conversation, the manipulated participants rated how they felt their behavior would be perceived by their conversation partner on a scale of 1-6 (the left bar chart below) and the participants with their back to the video screen reported on the same scale their perception of whether they felt listened to. The solid black bars are the tell: Participants who were instructed to put their energy into watching the videos assumed they would be perceived as less attentive (4.78 on the left side compared with 5.32 and 5.25 for the other two conditions), yet their speaking partners (right side) gave generally the same perceived listening rating to those distracted partners (5.18) as they did for the two other groups (5.36 and 5.42).

As part of this study, researchers also had each of the participants who had their backs to the video rate how well they felt heard by their partner and also asked the manipulated partners to self-rate how much they listened. This approach was slightly different than the first spin which focused on how well the listener felt they could skew perceptions of the speaker. The self-reported ratings in this second analysis got more at the question of whether speakers knew they were being punked. Listeners were honest raters of their attentiveness — those in the feigned and distracted conditions indeed reported less rapt attention. But once again, the speakers couldn’t differentiate, reporting similar levels of feeling heard regardless of the level of attentiveness the listeners were assigned or self-reported.

Outside Observers

As a check of sorts, the researchers had another 300 participants recruited on Amazon Mturk watch one-minute Zoom clips from this experiment. The Mturk participants were given tips on how to look out for nonverbal cues such as nodding and smiling, and to rate how often the listener used any of these cues.

Even with that nudging, the third-party read of these recorded conversations was predominantly inaccurate. The Mturk participants correctly guessed the assigned group of a listener 37% of the time, which is close to what random chance guessing would suggest, given the three possible conditions. Overall, listeners were pegged as being attentive 76% of the time, including 75% of the listeners who had been assigned the job of being fully focused on the video.

You’re Cutting Out …

Zoom technology made it possible for the researchers to build an experiment where the ability of the listener to actually hear the speaker was manipulated. More than 300 participants sat down for 10-minute Zoom chats with another participant. The researchers sorted the listeners into four groups and told everyone to convey that they were being a rock star listener. But in reality, the ability to actually hear their conversation partner was manipulated by the researchers.

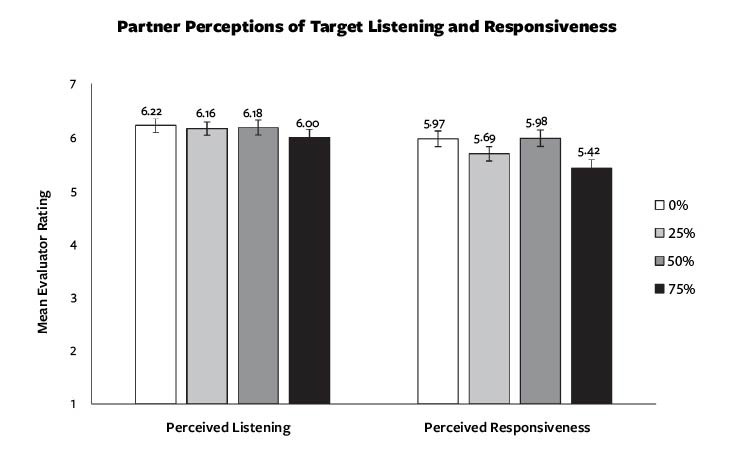

Some of the listeners heard the entire conversation clearly, another group experienced the speaker’s words being garbled 25% of the time, another had 50% garbled and another group of listeners experienced 75% garbling, which effectively made it highly unlikely they could have been an attentive listener. The participants on the other side of the convo were unaware of these garbling manipulations.

As shown in the left graphic below, the speakers/perceivers reported similar levels (on a 1 to 7 scale) of feeling the listener was engaged, regardless of whether the listener could hear 100% of the conversation (6.22) or just 25% of the conversation (6.00). The researchers also had all the speakers/perceivers rate whether they felt the listener was emotionally invested — “My partner made me feel heard” and “My partner made me feel validated” or “I felt that my partner cared about me.” The right graphic below shows that it was only when listeners were struggling with a 75% garbling that speakers/perceivers seemed to be aware there was a drop off in the quality of their partner’s listening.

Gee, Was I Listening?

The fallibility of physical cues to signal quality listening even makes it hard for us to correctly read our own behavior. The researchers had 90 participants listen to one story while they were asked to listen attentively and then they listened to a second story while there was music playing. In that exercise, some participants were told to focus on the lyrics, effectively giving them a multitasking job that would make it hard to be an attentive listener.

A few minutes after completing this exercise the participants viewed 10-second muted clips of themselves in listening mode and were asked to report if a clip was of them during their attentive story or multitasking (music playing) story. Overall, participants misread their own body language 36% of the time and in nearly half of the clips where a participant was multitasking (inattentive), the participant mistakenly reported that the clip was of them listening attentively.

Volley, Don’t Talk Over

With visible cues and grunts proven unreliable, Collins turned to more substantial verbal responses that demonstrate listening and comprehension. Within limits.

Collins’ plea for greater verbal confirmation isn’t a green light to hijack conversations or talk over each other. You still have to give others the space to communicate and listen to what they say. Nonverbal and paralinguistic (“mm‑hmm”) cues are an important part of that. But given that those gestures and utterances can also deliver a false‑positive perception that quality listening has occurred, Collins’ framework suggests the knowing nod, heartfelt eye contact and “mm-hmm” should be complemented with actual conversational feedback:

- Paraphrasing: “Let me make sure I have this right. What happened at school today was…”

- Conversational callbacks: “As you mentioned in your email last week, your team needs more support to complete this project on time.”

- Follow-up questions: “I hear that you’re asking me to do more around the house. What specifically would help?”

Words can also be an effective way to move tricky conversations forward. In a paper published in Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Collins, Harvard’s Michael Yeomans, Francesca Gino and Julia Minson and University of British Columbia’s Frances Chen, studied how language can make people seem more open when talking to someone they disagree with. A key part of the research was training an algorithm to detect specific linguistic cues — “I understand,” “I see your point”— that signals an openness to hearing opposing views.

Across multiple experiments involving nearly 2,500 participants, when a participant used phrases that signaled what the researchers call “conversational receptiveness” there was an increased willingness to engage with people with opposing views. In a related study, they analyzed real conversations between senior government officials discussing controversial policies. Those who used more receptive language were seen by their partners as better teammates and collaborators — even if they didn’t see themselves that way.

The researchers also analyzed conversations among Wikipedia editors, where disagreement about how to work or revise articles is common. They found that when someone kicked off a discussion using more receptive language — acknowledging others’ views, softening disagreement, or showing respect — they were far less likely to be personally attacked later in the thread. In fact, even when they didn’t fully agree, their tone helped keep things civil.

Collins, Georgetown’s Charles A. Dorison, Gino and Minson, in research published in Psychological Science, found across seven studies involving more than 2,600 participants that counterparts with deep partisan chasms — U.S. political beliefs, the Israel-Palestinian conflict — can be persuaded through explicit communication that their counterpart is open to learning.

Contagious Receptivity

The researchers establish that the default state is to assume one’s counterpart is not interested in the other side’s perspective. Moreover, participants tend to ascribe that closed mindedness more to their counterpart, while reporting they would be more open to conversation. Yet when the researchers intervened in multiple experiments by letting counterparts know the other person was indeed open to learning — that is, willing to actively listen — the walls came down a bit. “In both American partisan politics and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, counterparts and their arguments were evaluated more positively when participants believed that their counterpart was eager to learn about their perspective,” they reported

The potential of explicit expression of a willingness to listen and talk as an icebreaker is advanced further in a working paper by Minson, Yeomans, Collins and Dorison. The researchers found that one party stepping up with conversationally receptive language can become a positive contagion. Using an upgraded version of the conversational-receptiveness algorithm, they find that when one party expresses they are open to conversation/learning, the other party volleyed back with their own conversational receptiveness.

Importantly, the researchers teased out that the conversationally receptive response isn’t simply mirroring the same accommodative language used by their partner. The contagion is more indirect in that it spurred the other debater to reply with their own spin on receptive conversational signals. In essence, receptive language seems to inspire both parties to release their shoulders from their ears and listen in a more open and less-charged manner.

You Can Try This at Home

In their paper, Yeomans, Minson, Collins, Chen and Gino offer, based on the algorithm’s learning, four concrete ways to signal conversational receptiveness:

- Use positive affirming statements, not contradicting statements. For example,you should say “X is true” or “X is good,” rather than “Y is not true.”

- Acknowledge the other person’s views. Demonstrate listening by saying things like “I see your point” or “I understand where you are coming from.”

- Use “hedges” to soften your claims. For example, you could say, “X is partly true” or “Y is sometimes the case.”

- Try to find points of agreement. When you disagree, focus on some things you do agree with. For example, “I agree that it’s a difficult situation, which is why X,” rather than “That doesn’t work because Y.”

Regardless of the relationship and the tenor of a specific conversation, the universal takeaway from this advancement in listening research is to speak up. Verbally check in to both signal you’ve paid attention and make sure you are on the same page. As a listener that can be a simple, “So, you’re telling me” or “This is important, I want to make sure I understand.”

And when we’re in speaking mode, Collins’ research suggests we shouldn’t rely on our reading of a partner’s nonverbal cues, as there’s a good chance we will presume we are heard when we are not. Rather, the same verbal check-in applies, “Did what I just say make sense to you?” or “I am interested in your feedback on this, what’s your opinion?”

Featured Faculty

-

Hanne Collins

Assistant Professor of Management and Organizations

About the Research

Collins, H. K. (2022). When listening is spoken. Current Opinion in Psychology, 47, 101402.

Collins, H. K., Minson, J. A., Kristal, A., & Brooks, A. W. (2024). Conveying and detecting listening during live conversation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 153(2), 473.

Collins, H. K., Dorison, C. A., Gino, F., & Minson, J. A. (2022). Underestimating counterparts’ learning goals impairs conflictual conversations. Psychological Science, 33(10), 1732-1752.

Minson, J. A., Yeomans, M., Collins, H. K., Dorison, C. A. (2024). Conversational receptiveness transmits between parties and bridges ideological conflict. J. Personality and Social Psychology.

Collins, H. K. (2024). From Conversation to Connection: The Pragmatics of Conversational Listening. Harvard University.

Collins, H. K., Hagerty, S. F., Quoidbach, J., Norton, M. I., & Brooks, A. W. (2022). Relational diversity in social portfolios predicts well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(43), e2120668119.