The shift lends credibility to medicines vs. trials that exclude people 65 and older

Which diseases get targeted for new drug development in the United States is largely in the hands of pharmaceutical and biotech companies. Given the embedded profit motive, that can skew which therapies are pursued.

When a promising therapy is ready to move into the clinical trial phase, those firms also have free rein on whom they recruit to participate in the test. Historically, private industry has struggled to recruit a diverse population of participants for drug trials. Women, people 65-plus and Black patients are typically underrepresented.

A recent report in Mayo Clinic Proceedings noted that non-Hispanic white Americans of European ancestry comprise more than 90% of enrollees in clinical trials, despite comprising an estimated 60% of the U.S. population. The lack of a diverse trial population can have a profound downstream effect, given that age, race and other demographic markers can impact reaction to a given therapy.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

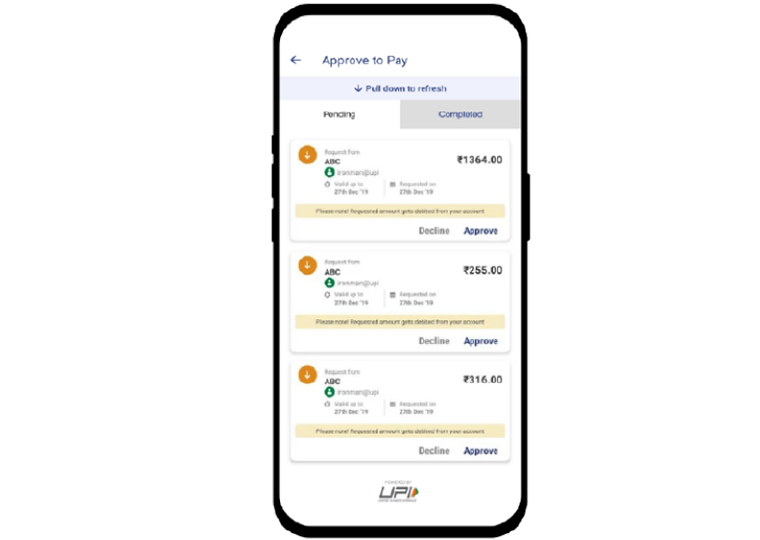

Reticence among potential enrollees is part of the challenge. For some, it may be a wariness of participating in an experiment. But a major hurdle can also be the potential out-of-pocket cost of participation, as drug developers often don’t cover the full tab, and insurance companies are typically not eager to pony up for coverage related to a drug treatment that has no track record.

Older Patients Sign Up

In a working paper that presents a real-world case study, UCLA Anderson’s Jennifer Kao and Ohio State University’s Tamar Oostrom present evidence that when some of the costs of clinical drug trials are shifted off the developers and off the potential trial participants, it triggers a series of related beneficial changes.

Drug developers expand the types of diseases they explore, and recruiting a more diverse group for clinical trials sees significant improvement. That is a crucial development, as studies have shown doctors are more likely to prescribe drugs to a given patient population — be it age or race, for example — when they have clinical data for that very type of patient. Moreover, patients can be more open to a suggested drug therapy when they are presented evidence of its efficacy in people just like them.

Kao and Oostrom focus on Medicare, the single-largest health insurer in the country. Medicare enrollment — age 65 is the standard age for becoming eligible — has grown from 51 million to 60 million over the past decade, and that number will continue to rise in the coming years as the last of the baby boomers age into the program that is already full of older boomers who are living longer.

In 2000, President Bill Clinton issued an executive memorandum that compelled Medicare to cover “routine” costs associated with clinical drug trials. Those routine costs effectively cover the bulk of clinical trial costs for participants.

That policy change gives Kao and Oostrom the ability to explore whether removing this financial barrier impacts the behavior of drug researchers and potential clinical trial participants.

400 Diseases Analyzed

The heart of the database they construct is pulled from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey , the largest ongoing source of detailed health care usage and cost. They identify more than 400 diseases that are associated with the Medicare (65-plus) population and build estimates for the percentage of each disease that afflicts the 65-plus population in the four years before 2000, when Medicare started reimbursing clinical drug trial costs.

That enables them to sort diseases into whether there is a high or low prevalence of Medicare-age patients with a particular disease, and to compare this level of “disease burden” with a global data set that tracks disease burden by a variety of demographics. They then wove detailed clinical trial data for each of the more than 400 diseases into their database.

Kao and Oostrom then set on analyzing the extent to which shifting the financial burden from patients and drug developers onto the federal government (and its taxpayers) impacted the business of drug research and trial participation. As a point of reference, prior research conservatively estimated that the average per patient cost to recruit and retain trial participants ranges from $43,000 for early-stage trials to more than $330,000 for late-stage trials.

Drug developers seem to have an increased interest in exploring treatments for those 65 and older. In the 10 years after Medicare started to reimburse for clinical trial costs, there was an 18% increase in clinical drug trials targeting diseases that the researchers have sorted into the “high Medicare” share bin. (Note: Medicare Part D, which provides reimbursement for prescription drug costs was passed in 2003 and went into effect in 2006; Kao and Ostrom ran additional tests to control for this possible influence on drug development choice and it did not change their core finding.)

Drug developers were also more eager to recruit patients 65 and older into trials. There was a 26% increase in clinical trials that specifically listed patients 65 and older as a recruitment goal; during the same period there was no increase in specific recruitment of younger patients.

Patients 65 and older, potentially responding to being unburdened from the financial cost of participating in a trial, were more eager to sign up. Kao and Oostrom found that 65-plus enrollment increased nearly 60% in drug trials for diseases that disproportionately affect those 65 and older.

Clinical Trials Expand Overall

All of these findings suggest the oft-cited reasons for the difficulties in 65-plus inclusion in research — cognitive decline, preexisting conditions that can muddy results — are not insurmountable obstacles.

Interestingly, there was also a commensurate increase in the number of younger-than-65 trial participants. Apparently, drug developers whose clinical trials were now receiving Medicare financing responded by running larger trials that benefited all age groups.

Kao and Oostrom also tease out a potential downstream effect on how better representation of those 65 and older— in drug development and clinical participation — may impact actual care. Clinical trial results are a key selling point when drug manufacturers pitch their products to doctors. The researchers find that in the decade after the Medicare Memorandum, the average number of per-patient prescriptions for 65-plus patients for diseases common among those 65 and older, increases by 23%. That suggests that doctors, and their patients, may be more comfortable using therapies when there is concrete trial data to base that decision on.

Featured Faculty

-

Jennifer Kao

Assistant Professor of Strategy

About the Research

Kao, J., Oostrom, T. (2023). The Effect of Insurance on Disparities in Trial Enrollment.