The figure is a subset, not covering huge expense of extended patents on high-priced biologics like Humira

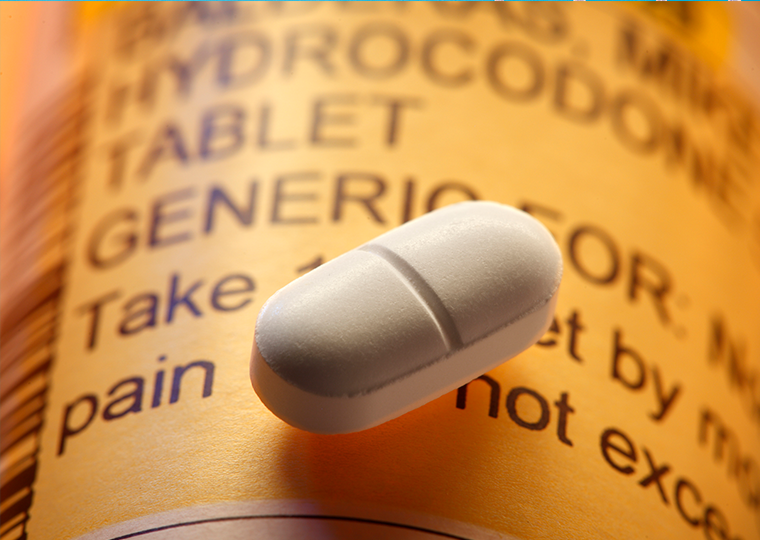

Pharmaceutical companies gain an average three years in monopoly protections on branded drugs by filing multiple secondary patents, throughout and beyond the development process, a study by UCLA Anderson’s Charu Gupta indicates. Unlike primary patents, which apply to a drug’s active ingredient, secondary patents can cover things like how the drug is administered, what disease it will treat and dosing.

These exclusivity extensions cost U.S. patients, insurance companies and other drug buyers about $148.3 million per drug by delaying competition from producing far cheaper generic brands, according to estimates Gupta describes as conservative in a working paper. In a sample of 355 branded drugs, she finds extended monopoly protection raised consumer costs by $52.6 billion.

As big as it seems, that figure covers only a subset of years and of the total drugs that enjoy patent extensions, as explained below.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

Though the topic of patent extensions has been much studied, Gupta’s work offers a causal estimate of how much secondary patents extend the monopoly life of a product, she says.

The findings relate to the controversial practice of strategic patenting, an approach inventors use to extend monopoly rights on a primary patent as long as possible. Called “evergreening” by critics or “life cycle management” by supporters, the strategy is a hot topic among regulators and watchdogs hoping to keep competition healthy, and products more affordable, especially in the pharmaceuticals and tech industries.

Despite years of contention over strategic patenting, Gupta says that there’s limited causal evidence on how well it works to delay competition. Her findings, she says, are pertinent to all sides.

Uncontested Patents Mean Longer Monopolies

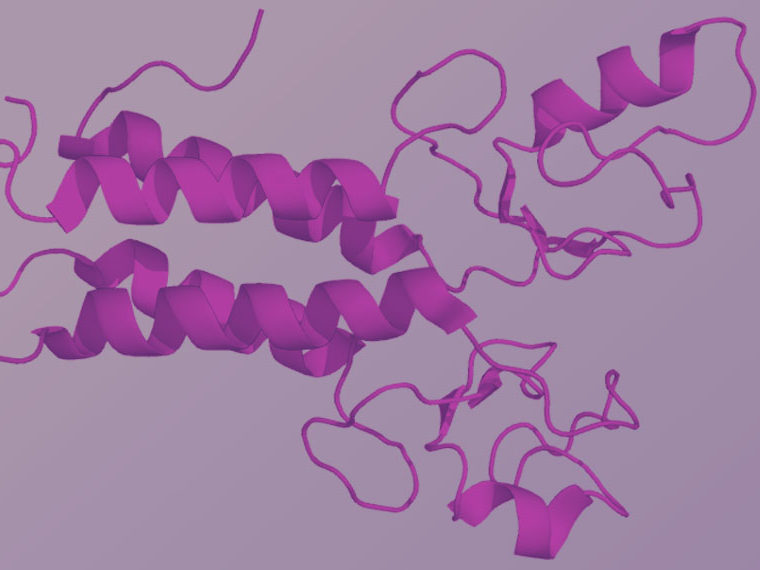

In the $485 billion pharmaceutical industry, the 20-year primary patent on a drug starts with the discovery of a single new molecule that will, if all goes well, become the active ingredient in a new drug. Unlike tech inventions, molecules have specific structures that are easily differentiated.

While tech patents are often successfully challenged by holders of previous patents, primary drug patents are almost always enforced, Gupta explains in a phone interview. The near certainty of at least 20-year monopoly protections made the drug industry a particularly good subject, she says, for isolating effects of secondary patents from those of successful challenges to the core discovery.

Because much of a drug’s 20-year exclusivity period is eaten up by development, testing and regulatory approvals, branded drugs average about 10.9 years on the market with monopoly rights with the primary patent intact.

Gupta finds that secondary patents extend the average selling monopoly to about 13.4 years in her sample, or by about 22%. Generic competitors spend considerable additional time and money developing ways around the secondary restrictions — for example, formulating it into a capsule instead of the protected tablet — or fighting the protections with lawyers.

If all of the secondary patents are enforced, the time from the branded launch to generic protection would extend even further, to 17.6 years, the study finds. But in many cases, Gupta notes, generic manufacturers overcome secondary patent restrictions in litigation, especially on strong-selling brands they really want to copy. Blockbuster drugs saw generic competition much earlier than less popular drugs, the study finds.

One Product, Many Patents

The pharmaceutical industry is often described as a “one patent, one product” industry because drugs generally have only one primary patent, Gupta notes. She goes on to describe an average 3.4 secondary patents on each drug in her study sample.

That seemingly low number — the 10 top selling in the U.S. average 74 granted patents — is due to the exclusion of some popular categories of secondary drug patents in the study’s sample.

Gupta built a working sample of 431 new chemical entities awarded between 1985 and 2010 and the patents that cover them, as listed in the Food and Drug Administration’s Orange Book. (The reference book lists all potentially enforceable patents related to the drug’s active ingredient, its formulation and approved uses.)

Importantly, Gupta notes, patents for drug manufacturing processes and unapproved uses — thousands of existing secondary drug patents — are not allowed in the Orange Book. These types of secondary patents may extend monopolies also, as the high costs of infringement and fighting them dissuade some generic competitors from taking on the original patent holders. Any effects of secondary patents outside of Orange Book parameters will not show up in these study results.

Gupta’s results also exclude effects from patents on biologics, a category of drugs that averages many more patents than the small molecule drugs included in the sample. Partly through what The Wall Street Journal terms “a wall of patents,” for instance, Abbvie extended the life of Humira, the world’s biggest selling drug, in dollar terms. The biopharmaceutical company has racked up more than $200 billion in sales of Humira, which treats rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases.

More Patents, Fewer Drugs?

Encouraging innovation is the key policy reason governments grant patents in any industry. Giving a drug developer temporary monopoly markets is supposed to incentivize pharmaceutical companies to create more life-changing treatments and cures, despite the huge costs and risks of pursuing them.

However, regulatory bodies in the U.S., the European Union and other parts of the world have grown skeptical that these secondary patents further the cause. In September 2023, the Federal Trade Commission put the U.S. industry on notice that it intends to scrutinize Orange Book patents for signs of unfair competition. The agency immediately followed through on the threat with challenges to more than 100 drug patents.

In recent years, the number of new breakthrough medicines has been falling, and some research suggests pharmaceutical companies are increasingly focusing on incremental drug development instead. Are governments unintentionally encouraging this trend by awarding these secondary patents?

“Not necessarily,” says Gupta. Her paper shows that more novel drugs are the ones receiving longer monopoly extensions from secondary patents, reducing concerns that these patents are being awarded for incremental drug development. Further, her estimates suggest that the monopoly extensions contributed to an increase in pharmaceutical R&D, as measured by clinical trials, of between 21% and 69%. However, these benefits to new drug innovation must be balanced against the costs from longer periods of monopoly pricing. This is an important trade-off for policymakers to consider as they design policies related to intellectual property rights and high drug pricing.

Featured Faculty

-

Charu Gupta

Postdoctoral Scholar

About the Research

Gupta, C.N. (2023). One Product, Many Patents: Imperfect Intellectual Property Rights in the Pharmaceutical Industry. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3748158

Gurgula O. (2020). Strategic Patenting by Pharmaceutical Companies – Should Competition Law Intervene? International Review of Intellectual Property and Copyright Law,51(9):1062-1085.

I-MAK (2018). Overpatented, Overpriced: How Excessive Pharmaceutical Patenting Is Extending Monopolies and Driving Up Drug Prices.

Light D.W.,& Lexchin J.R. (2012). Pharmaceutical R&D – What Do We Get for All That Money? BMJ (Overseas and retired doctors ed.), 345(7869), 22-25.

Correa C.M. (2011). Pharmaceutical Innovation, Incremental Patenting and Compulsory Licensing (No. 41). Research Paper.