Raising the crop is a communal project, more so than the work of wheat farmers, who’re less attuned to feelings of others

A test developed more than 20 years ago has enabled researchers to measure one of the key nonverbal forms of communication: the emotion we read into another person’s eyes.

A number of studies have used the Mind in the Eyes test to advance the theory that people who come from more interdependent societies are better eye-emotion interpreters. That makes intuitive sense, as the more you engage with and rely on other people — a collectivist culture versus individualistic — the more you have riding on being able to correctly read other people’s emotions and more opportunity to hone this skill.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

Those studies have focused on country versus country comparisons. In a paper published in Current Research in Ecological and Social Psychology, University of Chicago’s Thomas Talhelm, UCLA Anderson’s Sherry Jueyu Wu, HEUFT Systems Technology’s Chuang Lyu, ShanghaiTech University’s Haotian Zhou and Beijing Normal University’s Xuemin Zhang instead compare populations within a country, namely China. They do so in hopes of ruling out other factors, such as the religious or political differences across countries, that might have skewed previous results.

The researchers find that people with ties to a community that has historically been more reliant on an interdependent economy scored higher on the eye-reading test than participants who hailed from communities with a less interdependent economic structure.

Leveraging Rice Theory

Prior research, including work Talhelm collaborated on, established that rice farmers in China operated in a more interdependent ecosystem than wheat farmers (at least in the period before modern farming techniques arrived in China). Paddy rice fields require flooding. In China, rice farmers have historically relied on an interconnected irrigation network within their community that required coordination not just of the flooding and draining schedule, but of ongoing maintenance of the system. Wheat farming is less labor intensive and a more solitary endeavor.

The researchers used this intra-China difference between rice and wheat to further the study of whether cultural interdependency impacts the ability to correctly interpret eye emotions. The climate requirements of each crop provide an important geographic dividing line: Rice is a southern China crop, and wheat is a northern China crop.

An Emotional Eye Exam

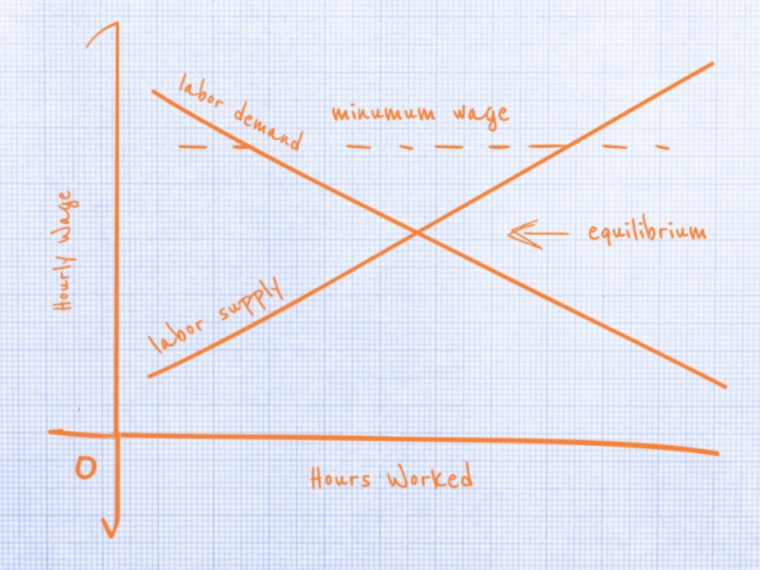

Across two studies, the researchers had a combined 350-plus participants complete the 36-question Mind in the Eye test. In this widely deployed test, participants are shown a cropped photo of a person’s eyes, given four options and then asked to choose the one that best describes the emotion they perceive in those eyes. The original test used photos of Caucasian actors; a later version employs Asian actors.

The correct answers for the two sample questions below are Insisting for the man and Playful for the woman.

An interesting angle to this research is that participants were not farmers but rather college students who were sorted into groupings based on their home region’s historical reliance on rice or wheat farming. The researchers used 1996 China census data that charted the use of cultivated land for different crops; that was a time when Chinese farming had yet to fully convert to more modern farming techniques.

In the first study (235 participants), students who hailed from provinces where less than 20% of the cultivated land was devoted to rice farming correctly answered 22.9 of the 36 questions correctly, on average. Participants from provinces with more than 70% of land used for rice farming had an average correct guess score of 24.9. Those results were controlled for a variety of factors, including gender and regional differences.

The second study focused on participants who were raised (or their parents were raised) in Jiangsu province, which has the added benefit of running right along the rice/wheat climate divide in China. The 104 participants were sorted into the province’s 13 prefectures (think: counties), which the researchers were able to sort based on the historic percentage of cultivated land used for rice farming before modernization.

This granular provincial focus effectively eliminated the potential for regional differences. And it produced an even more pronounced case that interdependency seems to foster more skill at correctly interpreting the emotional energy from another person’s eyes.

In prefectures with less than 50% of cultivated land used for rice farming, participants, on average, guessed right on 20.6 of the questions. In prefectures with at least 70% of land devoted to rice farming, participants on average answered 24.6 questions correctly.

This research adds another factor to what may fuel better eye-reading acumen. Previous studies have shown that women are better than men at eye reading, on average. And that people in lower social classes are better than wealthier people who can buy their way out of all sorts of interactions with other people, from avoiding mass transit to living alone.

“And even though fewer and fewer people in China are farming for a living, cultural differences that trace back to rice farming are living on in modern China,” the authors write.”

Featured Faculty

-

Sherry Jueyu Wu

Assistant Professor of Management and Organizations and Behavioral Decision Making

About the Research

Talhelm, T., Wu., S.J., Lyu, C., Zhou, H. Zhang, X. (2023). People in rice-farming cultures perceive emotions more accurately. Current Research in Ecological and Social Psychology, 100122.