The risk for matching platforms is affected by levels of fees and what’s disclosed about buyer and seller

Imagine booking a vacation rental through Airbnb, only to be contacted by the host and offered a discount to cancel your booking on the platform and rebook directly with the property owner. Would you do it? Many do. In fact, according to research, an estimated 5.4% of Airbnb transactions in Austin, Texas, are taken offline.

Circumventing the online platform has a name — disintermediation, or platform leakage.

You’ve probably already taken part in disintermediation on sites like Booking.com and Cheapoair.com. On these sites, once matched with a hotel or airline it’s easy to leave the platform and book directly — often at a slightly better rate since the commission to the platform is no longer included in the price.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

Disintermediation is a problem for two-sided platforms that match buyers and sellers. Upwork, eBay and Uber are additional examples of such platforms.

Good Information Begets Disintermediation

What seems like a win for both sides that were matched is a revenue loss for the platform that’s bringing them together. It’s one of the threats to the online platform business model, and companies try to prevent it by keeping the contact information of buyers and sellers hidden before the transaction.

Companies are also quick to warn participants that it’s risky to transact outside of their platform. Sowing fear of transacting offline is important as disintermediation has been cited — at least in part — for business failures at some platforms, such as HomeJoy, a home-cleaning platform.

In a working paper, University of Toronto’s Shreyas Sekar and UCLA Anderson’s Auyon Siddiq examine how the quality of information a platform provides to participants can play a role in disintermediation. The researchers suggest that platforms with high-quality information about participants are more vulnerable to disintermediation. Alternative pricing strategies are evaluated, including the unconventional move of raising commission rates.

‘Joe Was a Fabulous Guest and I Would Host Him Again’

It’s easier to ditch the platform when we know and trust the party on the other side of the transaction. That’s why we’re more likely to have tried it on Booking.com, with a branded hotel, than on Airbnb, with some random condo owner.

In the Airbnb example above, the host is unlikely to reach out to a renter who has no history on the platform. But if the platform shows that the prospective renter transacted many times through Airbnb and always received a high rating from property owners, the risk to the host of transacting off the platform would appear lower.

For this reason, the researchers suggest that while providing quality information is generally good for business, it’s only good up to a certain extent. A greater number of buyers and sellers are attracted to doing business on a site that gives them enough information to have confidence in the entity on the other side of the transaction and this can increase the platform’s revenues. But once the platform provides too much information, the risk of disintermediation grows.

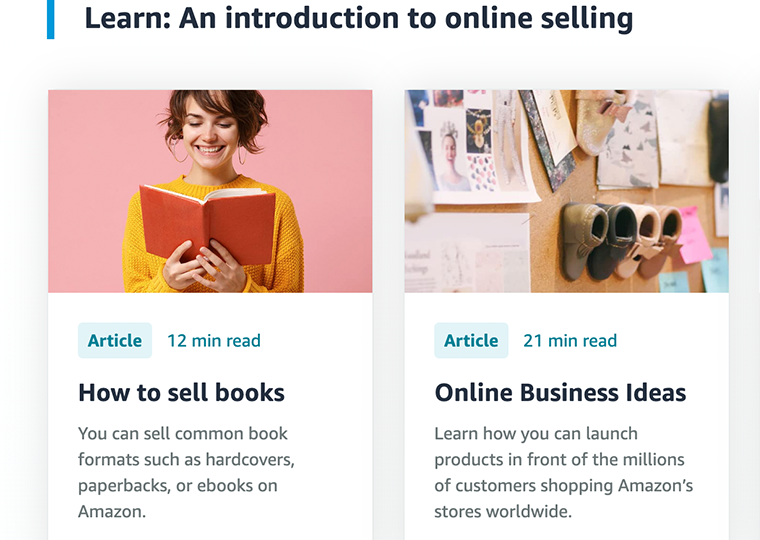

Of course, if the platforms matched users for free, disintermediation wouldn’t be a problem. Theoretically, the platforms take into account the difficulty and cost for sellers to acquire a buyer or client though other channels when setting commission rates.

| Fee Levels on Matching Platforms | |

| Airbnb | 3% paid by hosts, ~14% by guests |

| Uber | 25% of fare goes to company |

| Upwork | 10% paid by freelancers, 5% by clients |

| Amazon | 8%-45% paid by third-party sellers |

| Etsy | 6.5% paid by sellers |

| Booking | Hotels pay 15%, on average |

| Cheapoair | Airlines pay up to $35 per passenger, per flight in economy |

| Expedia | Big brands pay 10%-15%, independent hotels pay 15%-30% |

While the high commissions may encourage the platform’s users to disintermediate, the researchers suggest that the commission rates should be high to bolster revenues exactly because users disintermediate.

Risky Guests Are Costly

Sekar and Siddiq weigh price and trust in their study and only consider first-time transactions, since repeated transactions can increase the likelihood of disintermediation.

A base case where disintermediation doesn’t exist was first considered by the researchers. When there is no disintermediation, they found that as the quality of information increased, sellers’ prices fell. They suggest that the sellers lower their prices because they can eliminate risky buyers who’re costly to serve. As sellers’ prices fall, the lower prices attract more buyers to the platform. Since the platform’s revenue is commission based, falling prices hurt it, but the increase in transactions makes up the difference.

However, once disintermediation enters the mix, information can only rise to a certain extent before the platform’s revenue starts decreasing. Rising trust hurts a platform, such as Airbnb, as users start to disintermediate.

The researchers suggest Airbnb’s, or any other platform’s, optimal move is to increase its commission rates when its information quality reaches a particular point.

This point is dependent on the platform. Charging more to users who value the platform the most can offset revenue losses from disintermediation. In the end, platforms may receive a lot of flak about high commission rates, but the researchers’ work suggests it’s usually the platforms with high commission rates that provide users with the most information and have the highest quality sellers.

The researchers conclude that platforms need to consider their approach to the level of information provided and strategies for pricing when designing their platforms. Providing the right balance can build trust and discourage disintermediation.

Featured Faculty

-

Auyon Siddiq

Assistant Professor of Decisions, Operations and Technology Management