In New York, small and budget hotels — competitors to short-term rentals — raised prices

What business owner hasn’t had this dream: Government steps in and constrains the competitor that has been beating your brains out for years.

That’s what hotels experienced, to varying degrees, when local and state governments belatedly began regulating and taxing Airbnb and the rest of the short-term rental industry (hotels had long been regulated and taxed, of course).

Some background: There are some 5.29 million hotel rooms in the U.S., in recent decades segmented into price and amenity niches to cater to every possible traveler profile. The industry once pretty much had the traveler to itself.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

Enter Airbnb, a 2007 startup gassed up with large capital infusions around 2011. The company’s expansion turbocharged and urbanized an industry established earlier in vacation areas by VRBO and others.

The Path To Disrupting Hotels

By 2014, Airbnb had 10 million guests and more than a half million lodgings ranging from bedrooms, houses and apartments to castles and boats. In 2016, half the travelers surveyed in a Morgan Stanley report had already replaced a hotel room with a short-term vacation rental at least once in the previous 12 months. Hotel leaders consistently played down the threat but were certainly incentivized to pressure lawmakers across the country to rein in the industry.

Hotels might have complained about Airbnb to government officials. But the more compelling complaints, it seems, came from local workers who found their housing costs shooting up as traditional rental homes turned into hospitality suites for visitors. And from homeowners whose neighbors were replaced by rotating groups of not-always-well-behaved vacationers.

Remember, Airbnb did not go around knocking on city hall doors and asking for permission to operate what are essentially mini-hotels all over the country. It attracted hosts and guests and hit the gas pedal, with hotels and neighbors and municipalities left to figure out what happened.

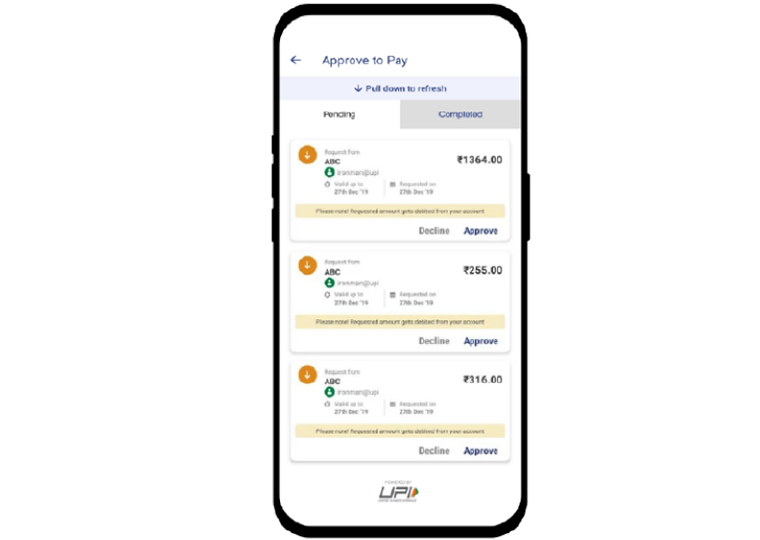

A paper by UCLA Anderson’s Yiyang Zeng, a Ph.D. student, and Mariko Sakakibara, published in Academy of Management Proceedings, uses adoption of Airbnb restrictions in the New York area to gather telling data on hotel competitive behavior. The study looks not at responses to Airbnb’s initial market entry, but at hotel behavior when government regulation began to provide the traditional lodging industry some breathing room.

The study focuses on comparisons of hotels in New York City and adjacent areas of New Jersey between January 2013 and December 2019, a time when short-term rental laws in each state were evolving and varied. For each establishment, an anonymized database provided details such as revenue, occupancy and price. The researchers also were able to sort the hotels by class (such as luxury or budget), size and location.

Government Levels the Playing Field

New York state first barred rentals of less than 30 days for most apartments in 2010, but the ban was widely defied. The state cracked down in 2016 with a hefty and enforced up to $7,500 fine on hosts that advertised an entire unoccupied apartment for rent for less than 30 days. New Jersey didn’t adopt similar laws until 2020, a delay that helped the researchers isolate the effects of legislation from other factors. (In 2023, New York City enacted an even more stringent limitation on short-term rentals, but that regulation is not part of this study.)

Hotels across categories and sizes benefited when laws restricted short-term rentals, according to the study findings. On average, hotels in areas with restrictions on short-term home rentals reported a 3.5% larger revenue increase than in places without restrictions.

Restrictions were especially helpful to hotels with limited resources, a category that includes many budget and smaller establishments, as well as some midscale and remotely located hotels (like near airports), the study finds.

Many of these resource-limited hotels successfully raised revenue by implementing above average price hikes when the new laws went into effect. For example, midscale and economy hotels that made aggressive price hikes raised their revenue by 19.8%, compared with the 7.4% revenue increase in those that made below-average price changes.

Hotels with fewer than 75 rooms gained an average 6.2% in revenue with the strategy. (For context, Zeng and Sakakibara calculate that a hotel with 40 rooms that made the average small establishment price increase gained an additional $144,000 in annual sales.)

Large hotels, including luxury hotels, were much less likely to respond with outsized rate hikes, according to the findings. Their price increases were 15% lower than the average hike in the small hotel group, and they reported lower average revenue gains than the small hotel group.

Featured Faculty

-

Yiyang Zeng

Ph.D. candidate in Strategy

-

Mariko Sakakibara

Sanford and Betty Sigoloff Chair in Corporate Renewal; Professor of Strategy

About the Research

Zeng, Y., & Sakakibara, M. (2023). Incumbents’ Strategic Responses to Gig Disruptors in the Hotel Industry. In Academy of Management Proceedings (Vol. 2023, No. 1, p. 12622). Briarcliff Manor, NY. 10510: Academy of Management.