Aiming high, with some flexibility to trip up along the way, spurs greater success

It’s hard to escape a goals-based life: going to the gym X days per week; saving Y dollars per month for retirement; meeting our weekly/quarterly/annual work deliverables.

Yet reaching goals is anything but easy. At the first sign of falling short, we tend to give up completely. A goal to lose weight is abandoned after an extra stressful day that is soothed by an In-N-Out run or a pint of ice cream. A long-term plan to build up savings bites the dust after one month of overspending. Even office high-performers can be prone to giving up on an assignment once they hit a speedbump.

In a series of multiple experiments spread across two research projects, Wharton’s Marissa Sharif and UCLA Anderson’s Suzanne Shu discovered a goal-setting hack that improves success rates. A plan that aims high but also allows one to trip up along the way is a compelling goal construct that causes people to stick with the goal longer, helps them reboot when they miss a goal milestone and provides a higher likelihood of reaching the goal.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

Their research makes the case for constructing goals with “emergency” cheat days/mulligans/get-out-of-jail-free cards built into the plan.

Pushing Ourselves with Some Give

Sharif and Shu find that a challenging goal with an “emergency reserve” is a Goldilocks approach that is preferable to easy goals, for which the bar is set too low to keep our attention, and to hard goals, for which the increased prospect of failing is a de-motivator.

First, researchers established that people have a preference for an emergency reserve. In one experiment, 100 participants were told their goal was to lose weight, and they were presented three options for a diet plan that used a point system. In the “easy” plan their daily food intake could add up to 32 points. In the “hard” plan they would be allowed 30 points. Option three was a plan that had a goal of eating only 30 points a day, but it also included two “emergency reserve” points; if participants hit 32 points, they would still be considered to have achieved their goal.

Participants gravitated toward the plan with the wiggle room. When given a choice between emergency reserve and the easy plan, 46 percent of participants chose the reserve, versus 29 percent opting for the easy plan. Reserve (46 percent) was also more popular than the hard option (25 percent).

Another experiment told 200 participants they needed to train to take a word-search test. There were three training runs; successfully completing each word search would earn the participant one point. The over-arching goal was to do well enough to qualify to take the test, and there were five different frames for success:

- Easy: Goal is to earn 2 points.

- Range – Easy: Goal is to earn 2 points, but 3 would be even better.

- Hard: Goal is to earn 3 points.

- Range – Hard: Goal is to earn 3 points, but earning 2 is okay.

- Reserve: Goal is to earn 3 points, but you have 1 “emergency reserve” point you can use.

When participants could choose between Reserve and Easy, two thirds went for reserve. When the choice was between Reserve and Hard, 72 percent chose Reserve. In both scenarios, two-thirds of participants felt they would be “significantly more likely” to qualify for the big test if they went with the Reserve plan.

Adding to the argument that flexibility is compelling, the “range” models were popular, too. Participants were evenly split when the choice was Reserve versus Range – Easy. When the choice was Reserve versus Range – Hard, it was Range – Hard (66 percent) that participants chose.

The Cost of Tapping Your Emergency Fund

The preference established, the researchers moved on to results. A key construct in the research is the use of the “emergency” frame. Labeling the built-in flexibility as an “emergency” makes it a more complex decision that can have a psychological cost, or an opportunity cost (if I use it now, I won’t have it for later). Shu and Sharif posited that the emergency reserve motivates people to persist in pursuing a goal, but with the intention of not actually using the reserve.

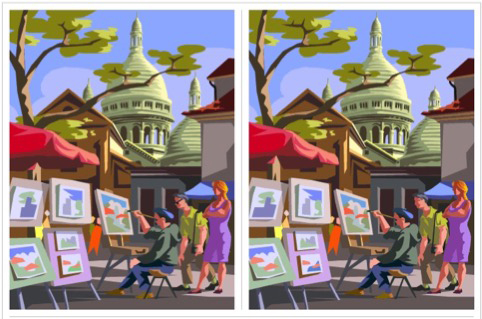

To explore that, they put 601 participants through an experiment that again set up three practice tests as the means to qualify for a bigger test. In this incarnation, the challenge consisted of visual “spot the difference” games, such as in the example below.

Participants were randomly sorted into one of six frames ranging from Easy (earn two points) to Hard (earn all three). In addition to the Reserve frame (goal is three points, but you can use an emergency point if you need it), this experiment also included a bonus point option that worked just like the reserve, but its framing as a “bonus” removed the psychological barrier of the word “emergency.”

The first game was made easy enough for everyone to pass. So they went into Game 2 with one point. For the second game, all participants were told there were 10–12 differences between the two images, but in fact there were only 10. Only the participants in the Hard condition had to pass the second game; everyone else went in knowing that if they failed, they still had Game 3 to meet their goal, or they could tap their emergency/bonus reserve to meet their goal. Yet as the graphic below shows, participants with the flexibility to fail on the second test and use a reserve kept grinding and ended up finding the most differences, on average.

“Participants with emergency reserves persisted more on the second game than even those with a Hard goal, suggesting that those with an Emergency Reserve goal want to resist breaking into their emergency reserve more than those with a Hard goal want to accomplish their goal,” write Sharif and Shu. That’s evidence that “the cost of the reserve” is a key motivating factor in trying to reach a goal.

In a follow-up paper, Shu and Sharif established that the emergency reserve construct compels people to get back to work on a long-term goal after they fail at reaching an interim goal that is part of the process.

In one study, more than 270 college students and staff participated in a month-long step-counting challenge. The week before the test began, participants tracked their daily steps on a walking app and reported it to the researchers (with screen shots to verify results). Each participant was then given a step goal during the ensuing month that was equal to 120 percent of their test week.

Participants were sorted into one of four goals:

- Easy: Reach step goal 5 days per week.

- Hard: Reach step goal 7 days per week.

- Reserve Weekly: Goal is 7 days per week, but you have 2 emergency skips each week (with no rollover).

- Reserve Monthly: Goal is 7 days per week, but you have 8 skips over the month to use at your discretion.

Participants in the Reserve scenarios reached their goals up to 40 percent more than the Easy and Hard groups. And they logged more steps (controlling for their personal daily goals).

Sharif and Shu were most interested in what participants did on the day after missing their daily goal. For each participant, they calculated the percentage of “days after” where they rebounded from the previous day’s failure and met their goal.

The persistence, or grit, was higher for the reserve-weekly participants (55 percent rebound rate) and the reserve-monthly group (47 percent) than for the Hard group (37 percent) and the Easy group (44 percent).

It’s not just that the emergency reserve engenders people to keep at a goal, it also seems to help them retain a positive mindset. In another experiment, 1,200 participants were run through a series of word-search games. In the second game, those with an “emergency reserve” were set up either to succeed or fail, and then the researchers tracked how many additional games those participants would complete. Results were nearly identical for the reserve-fails and the reserve-succeed participants.

“This suggests that emergency reserves are able to transform a sense of failure into a sense of progress, leading to maintained persistence both after a success and after a failure,” write Sharif and Shu.

This research suggests that an artful approach that aims high with some built-in flexibility can lead to more success, whether one is mulling a personal goal or tasked with setting goals for your direct reports.

Featured Faculty

-

Suzanne Shu

Professor Emeritus of Marketing

About the Research

Sharif, M.A., & Shu, S.B. (in press). Nudging persistence after failure through emergency reserves. Organization Behavior and Human Decision Processes. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2019.01.004

Sharif, M.A., & Shu, S.B. (2017). The benefits of emergency reserves: Greater preference and persistence for goals that have slack with a cost. Journal of Marketing Research, 54(3). doi: 10.1509/jmr.15.0231