A strong currency makes U.S. exports harder to sell, even outside of China

As the U.S.-China trade war deepens, American companies are scrambling to replace or supplement at-risk Chinese business with more sales in other countries. But a particularly strong U.S. dollar complicates the efforts.

U.S. dollar value is up sharply since President Trump began imposing large tariffs on Chinese imports in 2018. At the end of September, the U.S. Dollar Index was around 15-year highs, or about 9.5% higher than in January 2018. In other words, U.S. goods cost most foreign buyers considerably more than they did 18 months prior.

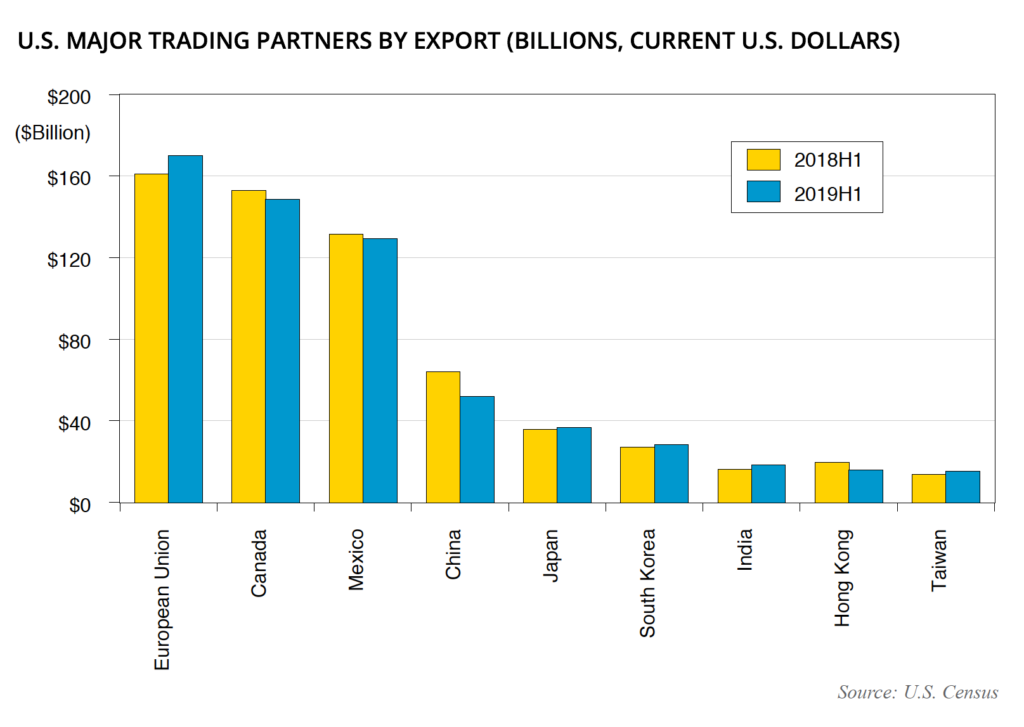

The strong dollar helps explain export figures analyzed in the UCLA Anderson Forecast’s September 2019 outlook. Note the changes in volume with several major trading partners, not just China, since the trade war took hold in early 2018.

While exports to China were some $12 billion lower in the first half of 2019 compared to the same period in 2018, U.S. companies also lost $10 billion in sales to Canada, Mexico and Hong Kong during that time, UCLA Anderson’s William Yu said. U.S. exports to the European Union, which has increasingly turned to the U.S. for oil and related products, rose about $8.8 billion.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

Threats of tariffs have little direct effect on currency markets, Yu explained. Rather, a country’s relatively high interest rates and economic strength typically attract investors.

However, the global economic uncertainty that trade wars induce often lead central banks to react in ways that inadvertently affect foreign exchange markets, even when currency manipulation isn’t the stated goal.

For example, in September 2019, the European Central Bank cut its interest rates and launched a bond-buying program in large part because the U.S.-China trade war has become “a major threat to the global economy,” according to ECB president Mario Draghi. He denied President Trump’s accusation that the ECB was trying to devalue the euro against the dollar.

The U.S. Federal Reserve cut interest rates in July and September 2019, which, theoretically, should have lowered the value of the dollar. But one of the key reasons the Fed cited for making the moves — economic weakness in other nations that could spill over into the U.S. — gives investors reasons to sell other currencies and buy more dollars. The cuts did not weaken the dollar against the currencies of its major trading partners.

Using tariffs to increase business on the home front, or to punish unfair trading partners, is tricky in other ways, too.

As Yu pointed out in the Forecast, many of the products the U.S. imports from Cambodia, Vietnam and Thailand contain a lot of parts that those countries imported from China. The U.S. helped facilitate China’s business by importing much more from these other countries in 2019.

Of course, the roughly 36% decline in exports to China and Hong Kong is the biggest factor in U.S. export weakness in 2019. China’s exports to the U.S. were down about 8% in the first half, but it is exporting more to other Asian countries and to the European Union.

Meanwhile, economists warn that any pain China or the U.S. feels from the trade war is also felt throughout the global economy. Fallout from the dispute will cut cross-border sales for businesses around the world, according to the World Trade Organization. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development gave a similar warning last month. Owing largely to the U.S.-China trade war, the OECD stated, the global economy is set to grow at the slowest pace since the financial crisis in 2008.

Featured Faculty

-

William Yu

Economist, UCLA Anderson Forecast

-

Jerry Nickelsburg

Adjunct Full Professor and Director, UCLA Anderson Forecast

About the Research

Yu, W., & Nickelsburg, J. (2019). The trade war deepens. The UCLA Anderson Forecast for the Nation and California.