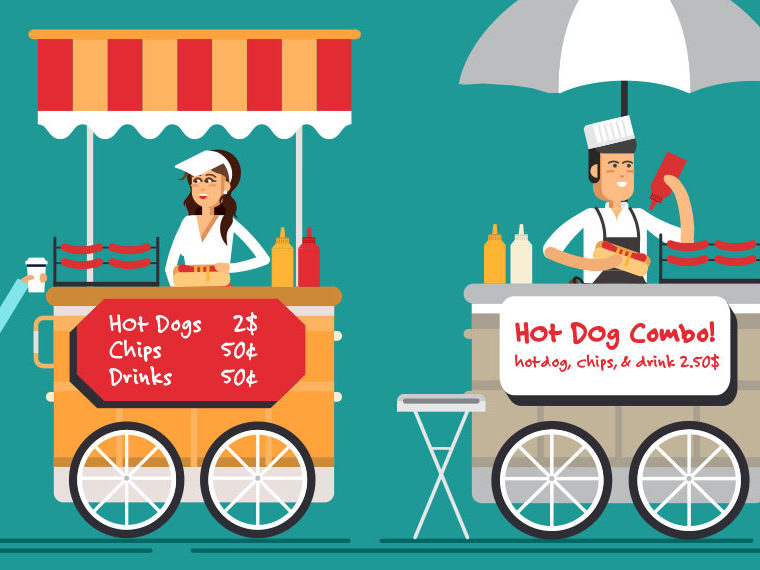

One platform dictates a price at 33% of retail — too steep a discount for many stores

Grocery stores, bakeries and cafés typically end their day with perfectly good food that will end up in a dumpster if it isn’t sold pronto. According to ReFed.org, U.S. retailers in 2023 had 17.2 million tons of food that never got sold.

A few startups are trying to reduce that waste by helping shops unload surplus food to bargain-hunting customers before it spoils.

One of the biggest players is Too Good To Go, a Copenhagen-based company, founded in 2016, that connects consumers with local stores willing to offer deep discounts on items nearing the end of their prime sales window. Too Good to Go operates in 19 countries and claims 175,000 merchants selling goods via the site to more than 100 million users of its app worldwide.

In the U.S., the app operates in more than 30 metro areas, and in mid-2025 Too Good To Go reported diverting about 1 million meals a month from the landfill.

Too Good a Deal?

A working paper by UCLA Anderson’s Alexandra Yizhuo Dong, a Ph.D. student, and Auyon Siddiq and Cornell’s Jingwei Zhang suggests that Too Good To Go could likely keep significantly more food out of the trash by recalibrating the size of the discount it requires sellers to offer consumers.

The researchers studied Too Good to Go’s operations in Manhattan, San Francisco, Boston and Seattle over a 64-day period in spring 2024. Their work suggests the company’s nationwide mandate that all food on the app be sold for just 33% of the retail price is likely keeping more businesses from joining.

They posit that the uniform price edict is a smart feature overall, but allowing stores in some large markets to reduce the discount by as much as half or so could draw many more businesses onto the platform — without chasing away shoppers.

Surprise Bags are Surprisingly Costly to Produce

The app doesn’t advertise specific food items, but rather Surprise Bags, from grocery store categories or restaurants, such that consumers have a general idea of what they might find in the bag. The Surprise Bag format gives the retailer flexibility on what exactly is in the bag. It also means not having to update the app about what’s available that hour or day.

App users reserve bags from nearby stores or eateries and then pick up the food. The researchers tracked operations across 465 shops, giving them a close look at how local conditions affect both supply and demand.

The researchers first estimated what it actually costs a shop in labor and materials to package, prepare and hand off a Surprise Bag, combining Google Places data (ratings, hours, shop type) with U.S. Census data on neighborhood density and income. The estimates exclude the sunk cost of the food that, but for the app, would go into the trash.

The average marginal cost per bag was $10.26 in Manhattan, $10.18 in San Francisco, $13.97 in Boston and $14.13 in Seattle. How could Seattle be costlier to operate in than New York? Costs are lower in dense, transit-friendly markets like Manhattan and San Francisco, where shops and customers are clustered close together. In Boston and Seattle, stores are more spread out, so the same staff effort yields fewer pickups — pushing up the per-bag cost.

Negative Margin

The marginal cost to stores and restaurants was more than double what consumers were paying: $5.42 in Manhattan, $4.95 in San Francisco, $4.79 in Boston and $5.52 in Seattle. That likely keeps many businesses from joining.

So, the researchers explored what might happen to participation — from sellers and consumers — if the mandated discount wasn’t so steep.

The researchers empirically confirm that set pricing — rather than letting every store set its own price — is indeed crucial to a marketplace with a social goal. If Too Good To Go abandoned price control, competition among stores could send pricing down and drive many out and suppress more wanting to join, reducing overall supply and sales by an estimated 58% to 83%, they estimate.

The problem, the researchers argue, is the magnitude of the current discount. They establish that allowing sellers to charge higher prices — meaning consumers get a smaller discount, and sellers earn more per bag — would draw more businesses to the platform and boost overall sales, as consumers will continue to use the app even with the less generous discount.

Their model recommends: in Manhattan, a 32% discount from retail prices; in San Francisco, a 27% discount; in Boston, a 22% discount; in Seattle, a 57% discount. At those levels, seller participation and total sales could triple or even quadruple in Manhattan, Boston and San Francisco. In Seattle, where seller costs and travel times are higher, the researchers would expect smaller but still meaningful gains.

Ratings and Travel Time

The study also looked at what draws customers to particular stores. Ratings mattered more in denser cities like Manhattan and Boston, where people are willing to travel a little farther for quality. In Seattle, where getting around can be slower and more expensive, convenience often won out over reputation. That pattern underscores how local conditions — city layout, travel time and density of shops and shoppers on the platform — shape how well these platforms can work.

The main finding — raising the price cap — offers a broad solution to keep more food out of landfills, but the city-by-city variation in optimal pricing underscores that digital platforms addressing social problems might do better avoiding one-size-fits-all policies.

Featured Faculty

- Alexandra Yizhuo Dong

-

Auyon Siddiq

Assistant Professor of Decisions, Operations and Technology Management

About the Research

Dong, A.Y., Siddiq, A., & Zhang, J. (2025). Empirical Market Design in Surplus Food Marketplaces. Available at SSRN 5648812.