The empirical study of happiness, a growth area at business schools, enters the classroom

Much of the research pumped out by business schools is aimed at making people, the organizations they work for and the overall economy more productive. Along the way, however, quality of life often suffers. Companies take on a hard edge. The competitive nature of work causes people to ignore their own well-being. And even when we do stop, look around and wonder what might make us happy, we often guess wrong.

UCLA Anderson’s Cassie Mogilner Holmes applies the methods of business research to the study of happiness. And after more than a decade of empirical work, she built a course officially titled Applying the Science of Happiness to Life Design, launched in 2019 and continuing in the January 2020 quarter.

A maximum of 40 students per class will keep a log of how they spend their hours, endure a six-hour digital detox, engage in expressions of gratitude, get more sleep and exercise, write their own eulogy and learn how to job craft — that is, to redesign a job to fit one’s own values, strengths and passions. The lessons connect to research by Holmes and others. Among the goals is to help students achieve greater life satisfaction and, just perhaps, become the sort of manager who would help others do so.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

During the initial class in winter 2019, Holmes says, “A bunch of students who were trying to manage their overall anxiety integrated meditation into their days. Many of them found that apps like HeadSpace were useful.”

Jeff Bailey of the Review caught up with Holmes to ask about the evolution of her research and teaching.

How’d you get into researching happiness? Did you encounter institutional resistance and, if so, how’d you overcome that?

I first got into this as a Ph.D. student in marketing, measuring people’s satisfaction with their choices — magazines, wine. Though fun, wanting a bit more satisfaction from my own choice of study, I began investigating people’s happiness with their more far-reaching decisions involving time. That started my line of research.

I haven’t come up with too much resistance, largely because I was able to show how it relates to marketers as they attempt to emotionally connect with their consumers. Also, there’s relevance from an organizational standpoint, how to recruit and retain talent.

Some of my economics-trained colleagues might question whether you can measure happiness. My response is, of course you can. Just ask people how they’re feeling.

With respect to offering a class, there was a little bit of resistance among the curriculum committee — a need to demonstrate rigor. That was easy to address, because my class is completely based on empirical research. And there is no question that the content is valuable for our students beyond landing a job or even their first year on the job, but for their careers and lives overall.

Reading your work, it seems many of us are going about the pursuit of happiness all wrong. Why is that?

When pursuing happiness, people tie money into that pursuit. If only I had a little more… The problem is, more and more money doesn’t lead to greater happiness; money is related to happiness only to the extent that it helps you meet your basic needs.

Over time, though, we get used to things, including our income level. This is called hedonic adaptation. We get used to what we have and think we’ll be happier if only we had a little more. When researchers have asked employees what salary would make them happy, the answer is always more than the person currently makes.

Social comparison is another factor: how we’re doing compared to those around us. How am I doing financially? How fancy is my car? How big is my house? As we become more successful, we’re surrounded by people who are also doing well for themselves. Our comparison group shifts up with us, and there’s always someone who is doing better on some dimension.

But the resource that is so tightly linked to happiness is time. That’s what I’ve focused on. We can continue to find joy in the wonders and the mundane that fill our day-to-day. We all have 24 hours in our day. The question is how to think about and spend time to make us happy and satisfied.

What are the lessons you’ve learned about time? And how does one apply them?

Shifting our attention from money towards time makes us more deliberate in how we spend time, compelling us to invest in happy and satisfying ways.

With respect to variety amongst our activities, the time frame matters. We should infuse our weeks and months and years with variety. But when we try to squish too much variety into the day, it makes us less happy. We feel scattered and like we’ve accomplished less, and a decreased sense of productivity hurts happiness.

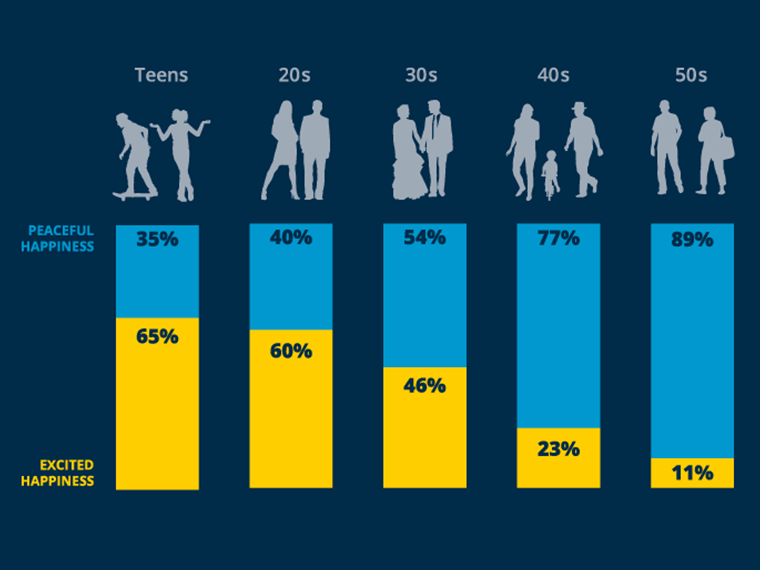

Where we are in our life matters — the amount of time left. Excitement vs. contentment. Ordinary things make us happier as we get older.

Looking into our time off, how much and how we make the most of it? Framing a weekend, say, as a vacation makes us happier. There’s a lot of value in personal time. It’s not just a break between the stuff that matters (i.e., work). It constitutes a meaningful chunk of our life. Plus, it translates into well-being and that translates into well-being at work.

Valuing time over money runs counter to the stereotype of jobs that newly minted MBAs typically occupy — and to the starting-salary question that figures prominently into business school rankings — working long hours for top pay. Is an adjustment in priorities due?

My research — and what I’m teaching — is a focus on the time you spend at work rather than the salary you’ll be earning as the metric of long-term success. We spend the majority of our waking hours at work, so we don’t want that just to be a means to an end. How we spend our workdays, even if it involves long hours, has to be in line with what we care about. Money is one factor, but shouldn’t be the primary one.

Students who take my course are trying to figure out what job to accept or how to optimize their time on the job they’ve selected. They start to realize that it’s not just a job, but the next phase of their life. So, people become more thoughtful about alignment with their individual values.

The syllabus for your class explains that individual happiness is good for larger organizations, societies, profits, even. Reminds one of the diversity-is-good-for-business arguments. Has it become time, even at a business school, for diversity and happiness to stand alone as worthwhile goals, rather than needing to boost business results?

Yes. We are educating students who’re going to have an impact both in the business world and society more broadly. We need to make sure that, as they enter the next phase of their career, and their life, we cultivate their well-being. To the extent we can, they’re less likely to burn out, and more likely to lead in a way that fosters well-being among other individuals in their organization. That said, I do think, it being a business school, it’s important to relate to the success of business. The happiness among constituents of a business does that.

You put students through a digital detox, have them keep logs of how they spend their time, have them engage in expressions of gratitude and kindness, tell them to get more sleep and exercise, write their own eulogy, and learn how to job craft. Take us through these and the impact on happiness.

Some of these have an impact in your day-to-day life, and some on your life more broadly. Both are important. We have to get the crazy hectic stress out of our weeks, but we also have to build a career and life that is satisfying.

Time tracking leads students to realize how precious their hours are. Then they become more thoughtful and purposeful in how they spend them. It is immediately apparent all the ways they waste their time, which gets quickly corrected. Ugh, that’s a waste of time, I don’t want to have to write that down!

Digital detox: What if people need to reach me? They realized early into those six hours how amazing it was to disconnect from the realm of social media, and to connect with what they’re doing and the people they’re with.

Sleep and exercise: We all know these are important, but we don’t create time for them. By having sleep be an assignment, people do it and it becomes so darn evident that being well rested makes them feel so much better, concentrate, and ultimately be more productive. Same with exercise. It makes the time we have more productive.

Eulogy and job crafting propel a broader purpose with work and life. Note that this all ladders back, because identifying one’s purpose informs day-to-day decisions about how to spend time.

Featured Faculty

-

Cassie Mogilner Holmes

Professor of Marketing and Behavioral Decision Making; Donnalisa ’86 and Bill Barnum Endowed Term Chair in Management

About the Research