Seen as a backstop to small- and midsized banks, the program, allowing insurance in multiples of $250,000, alters banking’s risk calculus

The typical American household doesn’t have to think much about the safety of money sitting at their bank or credit union. Federal deposit insurance automatically provides customers a generous $250,000 of protection per bank if anything goes wrong.

Yet the 2023 failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, which threatened to set off a broader banking crisis, made plain that plenty of banks have boatloads of customers — individuals, businesses, public entities — with deposits that exceed the $250,000 per-account/per bank insurance coverage limit. At the end of 2022, nearly 45% of total U.S. deposits were uninsured. At both Silicon Valley and Signature, more than 90% of deposits exceeded the insurance limit.

When news got out that both banks had investment-related balance sheet problems, many customers quickly withdrew their (unprotected) money, accelerating the banks’ collapse.

The government’s initial position when it took over both banks was that uninsured deposits wouldn’t be covered. Yet within 48 hours, as concerns grew of a wider run on U.S. bank deposits, regulators announced that all uninsured deposits would be covered.

Banking’s Moral Hazard

The decision to guarantee all deposits potentially undermines the market discipline that insurance limits are meant to impose and led the FDIC to size up its insurance fund more critically. The FDIC estimated that blanket coverage, as a stated policy, would require increasing the size of the fund by at least 70% from its current level ($129.2 billion as of June 30, 2024).

Beyond the added cost to banks (and bank customers, indirectly) to pay higher assessments into the fund, policy stakeholders also worry that blanket insurance could lead to excessive risk taking, a situation known as moral hazard.

Banks unconcerned about the potential flight of uninsured deposits might offer less customer-friendly terms. Moreover, if banks know their deposits are backstopped by the government, they might take more risk in loans and other assets.

In the aftermath of the 2023 regional banking crisis, a quiet financial innovation is gaining attention as a potential game-changer in the way we think about banking stability. It’s called “reciprocal deposits,” and though it may sound like a niche product for sophisticated investors, it could ultimately reshape the entire landscape of U.S. deposit insurance.

A working paper examines the growth of this deposit program to explore how blanket — or, at least, far heftier — insurance impacts bank and bank customer behavior. During the recent bank crisis, University of Michigan’s Edward T. Kim, UCLA Anderson’s Shohini Kundu and Michigan’s Amiyatosh Purnanandam find causal evidence that banks that made use of the FDIC’s “reciprocal deposits” mechanism, which enables them to effectively deliver insurance coverage well beyond $250,000, had stickier customers during the turmoil, offered less advantageous deals to customers and invested bank assets in somewhat longer-term bond positions.

Reciprocal deposits allow banks to insure large deposits beyond the $250,000 FDIC limit. Banks in this network break up their large deposits into smaller amounts, each within the insurance limit of $250,000, and place them with other banks in a reciprocal manner. In other words, participating banks effectively help insure a piece of each other’s large deposits so that they stay within the FDIC’s insurance limit.

Unlike the traditional deposit insurance system, reciprocal deposits incorporate a built-in mechanism of market discipline: Depositors can choose which banks to include or exclude from receiving their reciprocal deposits. This feature makes reciprocal deposits a fundamentally different alternative to standard deposit insurance by merging regulator-provided coverage with market-driven oversight. While these two tools have typically been seen as separate, and at times conflicting, methods for managing the behavior of banks and depositors, the combination of both in reciprocal deposits offers a novel approach. “One key motivation for our research is to assess the costs and benefits of this system, as countries worldwide explore alternative models for deposit insurance,” the authors write.

How Reciprocal Deposits Work

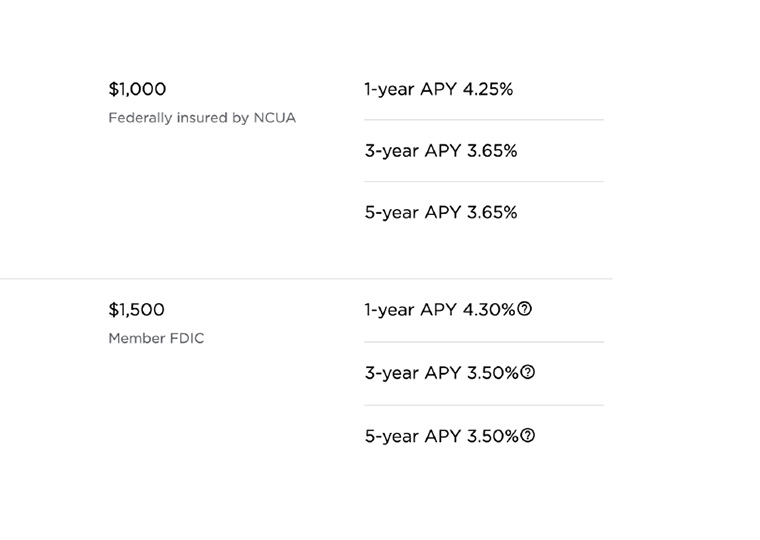

For nearly 20 years, the FDIC has permitted banks that participate in the “reciprocal deposit” mechanism to effectively insure customer accounts beyond $250,000 by spreading any excess money to other participating banks. Uptake was muted until 2018, when the FDIC tweaked the program to make it more cost-effective and regulatory-friendly for banks.

Too-big-to-fail banks implicitly don’t need to sweat high levels of uninsured deposits on their balance sheet as they also implicitly know they are in line for a federal bailout if things get hairy. But as the graphic below shows, smaller and midsize banks that don’t have that luxury have since 2018 increasingly used reciprocal deposits as a way to keep high-deposit customers.

The researchers focus on small and midsize banks from 2011 (when the current explicit $250,000 insurance coverage went into effect) through the end of 2023. Their universe includes more than 1,500 “network” banks that use reciprocal deposits and more than 3,000 that don’t.

Banks that delivered high-deposit customers insurance coverage through the reciprocal network saw a bigger jump in insured deposits and total deposits than nonnetwork banks during the tumultuous period from 2022’s fourth quarter to the same period in 2023. The gray shaded area demarcates when Silicon Valley Bank failed.

Not only is that a significant positive for maintaining bank and system stability during market turmoil, the researchers note that this could help level the playing field between smaller operators and behemoth banks. Currently, large-deposit customers are incentivized to spread their business across multiple banks; too-big-to-fail banks are the big winners from this dynamic. If a customer is assured that a single bank can provide comprehensive deposit insurance through the reciprocal network, they are less likely to feel the need to spread their money across multiple banks or favor large, dominant institutions.

Asset Risk at Banks on the Reciprocal Deposits Network

Banks offering reciprocal deposits leverage the increased stickiness of their deposits to their advantage. The researchers report that the interest rate on certificates of deposit of at least $10,000 was on average 11 basis points lower in 2023 among network banks than nonnetwork banks.

Network banks also took more interest rate risk with their investment portfolios, increasing their holdings of longer maturity bonds by nearly 4%. The median average maturity of bonds for network banks in this study was 9.25 years compared with 7.72 years for nonnetwork banks.

“While we do not evaluate whether this increase in interest rate risk is efficient, the heightened level of risk itself is a critical consideration in banking regulation,” the authors write.

Featured Faculty

-

Shohini Kundu

Assistant Professor of Finance

- Amiyatosh Purnanandam

About the Research

Kim, E.T., Kundu, S., & Purnanandam, A. (2024). The Economics of Network-Based Deposit Insurance.