A well-intentioned best practice, gender matching might not be optimal

Homophily — the habit of seeking out connections with people with similar traits — is a central tenet of mentorship. Unlike hiring, lending or renting, where using race or gender is illegal, it’s considered a feature, not a bug, of mentorship.

More than 8 in 10 working women recently surveyed said having a female mentor was important. Staying in one’s gender lane is also often baked into formal programs. A survey of highly rated U.S. colleges and universities found that nearly all offered a mentorship program for women in STEM fields, and in those programs, matching women with women is very common.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

Research by the University of Chicago’s Yana Gallen and UCLA Anderson’s Melanie Wasserman confirms that women are prone to seek out female mentors. But the heart of their research exposes that women seeking out women mentors is not because of some core belief that it is somehow advantageous. Rather, it seems to be a default deployed in the absence of more meaningful criteria from which to choose a mentor.

When Gallen and Wasserman filled the informational vacuum with quality ratings of mentors, female undergrads no longer showed any preference for a female mentor.

Gender Is Just What’s Available

The researchers found gender homophily at play in an analysis of how more than 3,300 undergraduate students used an online mentor-matching service to connect with alumni for the purpose of getting career advice. Female students were 36% more likely to seek out female mentors than male mentors.

Gallen and Wasserman note an upfront “cost” to that choice, as female mentors are 12% less likely than male mentors to respond to messages sent from female students.

Gallen and Wasserman recruited more than 830 UCLA students for an experiment designed to explore what might be driving women’s preference for women mentors.

Participants were presented with 30 pairs of potential mentors and asked to choose a preferred mentor from each pair. Each hypothetical mentor was identified with a name that “unambiguously conveys gender,” their profession, how much time they might have to connect, the year they graduated and whether they were a first-generation college graduate.

Some participants were fed star ratings from a past mentee across three variables: how knowledgeable the mentor was about job opportunities, how easy to talk to/friendly the mentor was and whether the mentor gave personalized advice.

When students (male and female) didn’t have quality ratings to assess, both genders had a strong tendency to choose a mentor within one’s profession. Yet the researchers found that female students alone exhibited a preference for female mentors. Female students were willing to pass on a mentor in their preferred occupation 28% of the time to instead connect with a female mentor outside of their field. Male students made that trade-off just 5% of the time.

Filling the Information Void

Once students had quality ratings to base their choice on, that information drove decision making for both male and female participants. But its impact is strongest on women, who without that information are prone to use gender as a choice crutch.

With access to quality ratings, the researchers found female students’ willingness to give up occupational match to obtain a female mentor “indistinguishable from zero.”

This experiment also seems to suggest that sexual harassment worries do not drive women’s tendency to choose female mentors. The researchers found that the gender of the past mentee who provided the quality rating did not matter to participants. That is, female participants valued ratings from female and male mentees equally (as did male participants).

“Female students do not require another woman to vouch for a mentor prior to mentor selection, as would be the case if female students preferred female mentors due to the fear of sexual harassment by male mentors,” they write.

Further analysis makes a case that the use of gender as a sorting tool among female students was merely a matter of convenience, not conviction.

Half of the women in this experiment said mentor gender was important, compared with 10% of men. Among the women who said gender mattered, 85% ascribed it to the fact that women are friendlier/easier to talk to. Fewer than 10% said it was because women were a better pipeline for job opportunities.

But once women were given additional (and more consequential) information on which to base their selection, “female students would rather have a mentor of a different gender than sacrifice mentor quality,” Gallen and Wasserman conclude.

Well-intentioned stakeholders running early career mentorship matching programs might want to ditch the gender focus and reorient the process to focus on mentor quality. That benefits everyone, but might be especially helpful in encouraging women to get the best possible help to navigate a working world where women are underrepresented in upper management.

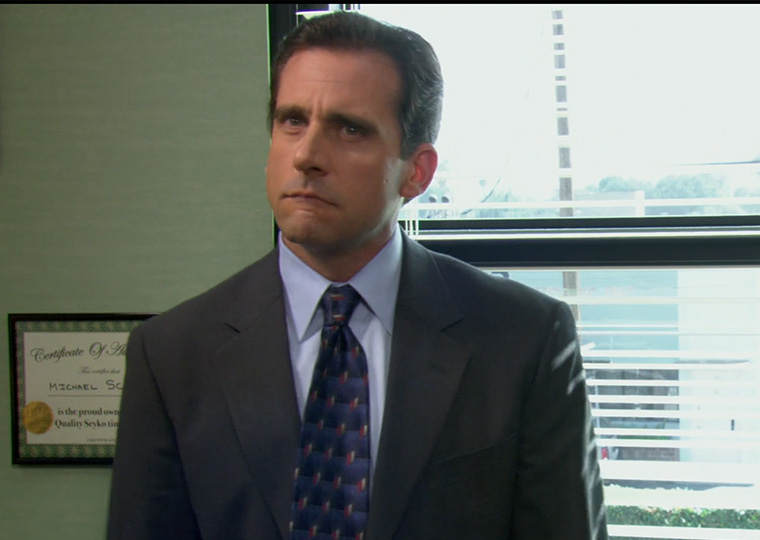

Featured Faculty

-

Melanie Wasserman

Assistant Professor of Economics

About the Research

Gallen, Y., Wasserman, M. (2022). Does Information Affect Homophily?