Study suggests husbands, unlike wives, don’t retain information spouses pass along

The idea that men don’t listen to their wives is a well-worn trope, and one that doesn’t seem to die: The very of-the-moment comedian Nate Bargatze complains on stage that he can’t possibly have ignored his wife Laura’s words as often as she claims.

Tuning out one’s better half isn’t generally treated as a big problem in otherwise healthy relationships. Economic theory assumes that husbands and wives purposely pool information — they seriously consider each other’s wisdom — on issues that affect their shared goal of strengthening the household.

But a working paper suggests that Mrs. Bargatze might know of what she speaks. In heterosexual couples, women incorporate pertinent information from their spouses, according to the researchers’ observations. Men do not.

Assessing Barriers to Info Flow in Households

Across-the-board sexism, as in a disregard for anything a woman says, did not appear to be a factor in the dismissive way the husbands treated data their wives conveyed, University of Heidelberg’s Dietmar Fehr, UCLA Anderson’s Ricardo Perez-Truglia and George Mason University’s Johanna Mollerstrom write. Husbands heard, and later acted on, that information when it came directly to them from the study’s female researchers. But when wives received the same information directly from researchers and passed it on to their husbands, the husbands did not appear to remember it a year later.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

The study does not rely on the kinds of surveys or laboratory experiments more commonly used in this field. Instead, researchers conducted a carefully designed field experiment involving about 1,000 German households that included heterosexual couples. (Some subjects weren’t part of a married couple.) In 2017 and 2018, they held individual, private conversations with all adult members of the households.

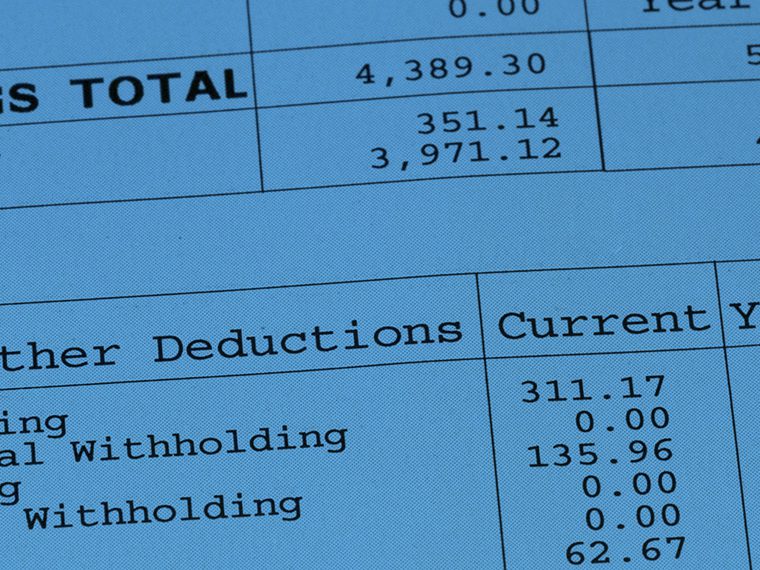

In the first meetings, each household member was asked to estimate where their own household income fell in national and global rankings, on a scale from zero (lowest) to 100 (highest). They were told they could earn real money if they guessed correctly.

In those first meetings, the researchers flipped a virtual coin to decide whether to provide the household member with information on their true income ranks. As a result, the true rankings were given to only one spouse in some households, both in some or neither in others. The researcher gave no instructions about whether or not to share this information, and they did not tell the subjects there would be follow-up interviews. They didn’t attempt, as some studies do, to track conversations within the household.

A year later, researchers returned to repeat the incentivized question. Afterward, they asked if the correct answer had been shared between spouses in the previous year — the information sharers were about as likely to be wives as husbands.

Based on previous studies about memory, researchers did not expect many subjects to recall the correct ranking exactly a year later, regardless of how they received the data. Information retention was measured by how many points closer the subject got to the correct answer in the follow-up.

The Source of Retention

When subjects heard the correct ranking directly from a researcher, they made significantly more accurate estimates in the second interview, whether or not they were married. Men and women each updated their answers to close the gap between their first estimates and the correct number by about 20%.

Notably, wives also made that kind of progress when their husbands received the information from the researchers.

But husbands appeared to learn nothing from information their wives received. Instead, they relied on their own previous beliefs. Unless a researcher had personally told them the correct rank, their estimates in the following year barely changed.

“Specifically, when only the husband receives the information, it influences the wife’s beliefs; however, when only the wife receives the information, it does not affect the husband’s beliefs,” the researchers write.

The researchers looked, unsuccessfully, for factors other than marriage itself that might have led the husbands to reject, consciously or not, facts presented by their wives. For example, maybe men’s views carried more weight in these discussions among couples, since most of them contributed more to the household income than their wives. But men who made less than their wives were no more likely to remember (or perhaps accept) what their wives told them about rank, according to the data.

Featured Faculty

-

Ricardo Perez-Truglia

Professor of Economics; Justice Elwood Lui Endowed Term Chair in Management

About the Research

Fehr, D., Perez-Truglia, R. and Mollerstrom, J. (2024). Listen to Her: Gender Differences in Information Diffusion Within the Household. Journal of Public Economics, 239, 105213.