Equity volatility can encourage — or dampen — investment, depending on a firm’s bond spread

Economists have long observed that the broader economy is more closely linked to the bond market than to the stock market.

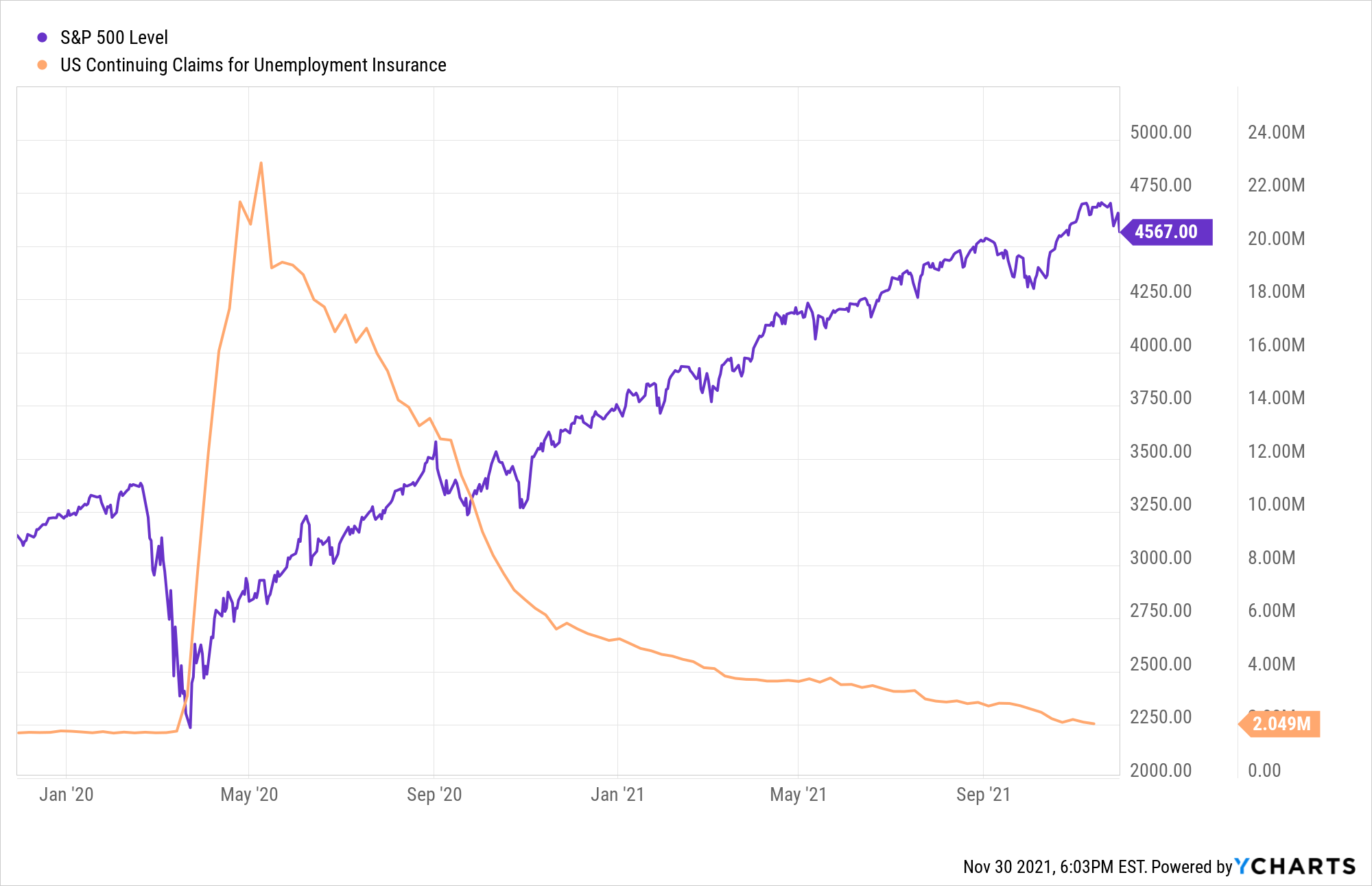

Indeed, equities often seem to take on a life of their own, as witnessed by the stock market’s more than 30% plunge in just five weeks during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, followed by a doubling of stock prices since then, even as the pandemic grew worse, claiming hundreds of thousands of U.S. lives, shuttering hundreds of thousands of businesses and idling millions of workers.

The bond market regained an air of normalcy after going through spasms in March 2020, but only after dramatic intervention by the Federal Reserve to provide credit to large employers and to purchase their existing corporate bonds and otherwise backstop nearly all U.S. credit markets.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

One explanation offered for these diverging patterns is that bond market investors, typically institutional investors, are the “smart money,” while people participating in the stock market are more likely to be retail investors with a lesser grasp of economic and financial fundamentals.

How Operating Firms Decide to Invest in Productive Capacity

A working paper by UCLA’s Huifeng Chang, a Ph.D. student, Stockholm School of Economics’ Adrien d’Avernas and UCLA Anderson’s Andrea L. Eisfeldt posits an alternative explanation, examining the crucial role of bond prices in corporate decisions to invest in productive assets, or to hold off investing.

The authors examine what they call the “investment channel,” looking at how operating firms make investment decisions for their business in response to both volatility in equity prices and credit spreads (credit spreads are the yield at which a bond trades relative to a Treasury security of a similar duration, and a wide spread indicates financial weakness).

Since investment translates into the upgrading of property, plant and equipment — in turn bolstering supply chains, creating jobs and lifting the overall production of goods and services — it directly boosts the economy.

Picture two publicly traded firms in the same industry, one, Leveraged Corp., that has a tremendous amount of debt and one that doesn’t, Prudent Corp. When their stock prices fluctuate wildly, that’s considered high equity volatility, a measure of the amount of price change. High volatility in a stock price indicates that the firm is capable of either a very high valuation or a low one; it also suggests uncertainty in, or disagreement about, a firm’s future earnings. For a given level of fundamental volatility, Leveraged Corp.’s equity value will fluctuate more wildly than Prudent Corp.’s due to the leverage effect.

When the cost of borrowing, through issuing corporate bonds, rises — i.e., the credit spread widens — that’s a sign lenders are less than confident in the issuing firm’s earnings potential and less certain it will be able to repay its debts. The wider the credit spread, the closer a firm is to default.

Now keep in mind that, in the event of a default, creditors are first in line to be repaid, and common stockholders are last.

Stock prices aren’t irrelevant to capital investment decisions. Previous research has shown that firms’ investment decisions respond to both equity volatility and to credit spreads: The riskier a firm appears, as measured either by its volatile share price or by its widening credit spread, the less likely its management will be to make investments.

And these two measures of risk do not operate independently. They interact to affect a firm’s prospects and therefore its investment decisions. A firm having both risky debt (in the highest third of credit spreads in the authors’ sample) and a volatile stock price, predicts lower investment; a firm having low-risk debt (in the lowest third of credit spreads) plus a volatile stock price positively predicts investment.

This illustrates that it is not simply the volatility of the share price that predicts investment decisions but also the interaction of a firm’s risk profile (as measured by its credit spread) with its stock price movements.

Another Factor: the Changing Value of a Firm’s Assets

The researchers study U.S. firms (excluding financial firms and utilities, which tend to operate with high debt loads) between 1984 and 2018, focusing on the relationships between five variables:

- Investment rates, defined as quarterly capital expenditures as a percentage of the firm’s existing net property, plant and equipment

- Equity volatility, as measured by daily realized stock market returns

- Credit spread

- Market leverage, or the ratio of the market value of a firm’s assets to the market value of its equity

- Asset volatility, which measures changes in the fundamental value of a business’s total assets. For example, the value of Purell’s inventory went up when demand for hand sanitizer soared in the early days of the pandemic, demonstrating high (and some might say surprising) asset volatility. Another way of thinking about asset volatility is that it represents equity volatility, but without the leverage; in the paper, the authors arrive at the value of asset volatility by de-levering equity volatility.

The researchers pull quarterly data for any firm that has been in the panel for at least three years, yielding 1,161 firms with 54,033 firm-quarter observations. They split their sample into thirds: A low-risk firm is one with a credit spread of 147 basis points or fewer; a medium risk firm with a spread between 147 and 326 basis points; and a high-risk firm has a credit spread of 326 basis points or higher.

They find that firms with narrow credit spreads, such as Prudent Corp, have a positive investment response to high equity volatility. If a firm’s managers see high potential upside and a low risk of default, they are keen to invest in future projects for the firm. Since Prudent Corp. doesn’t have any major loan obligations or expensive debt payments, it has the financial freedom to invest in resources (such as property, plants or equipment).

On the other hand, firms with wide credit spreads, such as Leveraged Corp., are disinclined to invest in the face of equity volatility. This makes intuitive sense. Leveraged Corp.’s managers and shareholders might think, “Hmm, given this observed uncertainty and the big pile of debt already outstanding, perhaps it’s not the best idea to build another factory.”

In other words, high equity volatility can affect investment decisions in either direction, but it depends on how near or far a firm is from insolvency.

The long-standing idea that a firm’s share price holds less predictive power than a bond yield comes from the fact that, taken in aggregate, the different effects of equity volatility across firms cancel out. The low price of a range may indeed be predictive of some firms’ futures, while the high price of a range may predict that of others.

This gives the false impression that equity volatility has a neutral effect on investment decisions and doesn’t have a close relationship to the broader economy. By observing the “investment channel,” or how a firm’s risk of default (as measured by bond yields) interacts with asset volatility to encourage or discourage investment, the authors suggest why bonds are a better predictor of investment, which in turn ripples out into the economy.

“Our results indicate that the closer relation between bond markets and the macroeconomy is not due to differences in the investor base,” the authors conclude, “but instead is due to the precise transformation of asset volatility and leverage that they represent.”

Featured Faculty

-

Andrea L. Eisfeldt

Laurence D. and Lori W. Fink Endowed Chair in Finance and Professor of Finance

About the Research

Chang, H., d’Avernas, A. & Eisfeldt, A.L. (2021). Bonds vs. Equities: Information for Investment. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3841206