Even before Dodd-Frank rules, the costs were significant

The world of finance is full of elegant formulas and models that traders use to price assets, taking into account time horizons and other risk factors. These formulas help determine the prices of derivatives — contracts between two or more parties, whose value derives from the price of a more straightforward regular asset (a barrel of crude oil, for example, or a Treasury bond.)

One well-known formula, the Black-Scholes asset pricing model, uses standard inputs — the strike price of an option, volatility, the duration of the options contract, the current price of the asset and the risk-free interest rate — to estimate the theoretical value of derivatives of other underlying assets.

However, these formulas do not always reflect the prices of derivatives contracts in the real world. Why is this?

Implicit Cost Drives Up Derivatives Pricing

One reason is that the funding rates for derivatives — the cost of credit to affect a trade — are not always the same as the financing rates in the cash market. This, in turn, can be attributed to the fact that derivative transactions are structured in such a manner as to take up space on the balance sheet of a financial intermediary. In contrast to simply borrowing cash in order to buy the underlying security — a transaction that can be completed in a matter of minutes — a derivative must remain on a bank’s balance sheet for the duration of the contract. Thus, there is an implicit cost to “renting” this space over a set period of time.

In a paper published in The Review of Financial Studies, University of Delaware’s Matthias Fleckenstein and UCLA Anderson’s Francis A. Longstaff show how the cost of renting intermediary balance sheet space explains seeming mispricing in a wide range of derivatives markets, well before the financial crisis of 2008-2009 led to regulation that imposed higher costs on capital.

First, a quick review of the role that intermediaries — banks, essentially — play in facilitating derivative transactions. If an investor wants to make a bet that a security will change in price, that investor can do one of two things: Buy the security at its price on a given day, and watch it go up or down, or use a derivative contract to take a “synthetic position” in the security by betting with a counterparty on which direction it will move.

The intermediary that stands between the investor and the counterparty will execute this transaction by placing both the derivative contract and the underlying security itself on its balance sheet for the duration of the contract. But using a bank’s balance sheet incurs costs, including but not limited to:

- Debt overhang costs, the increased cost a highly leveraged, or undercapitalized, bank may incur (and charge) to occupy space on its balance sheet.

- Cost of collateralizing liabilities (i.e., having enough assets available relative to liabilities on a balance sheet).

- Cost of funding illiquidity.

- Haircuts (the difference between market value of an asset and its collateral value to secure a loan).

Thus, the financing rate the bank will charge will not simply be the risk-free interest rate typically used in the Black-Scholes model. Instead, it will be higher due to the balance sheet usage costs.

Looking at the Implicit Funding Rate Versus the Repo Rate

The authors examine the interest rate futures market, which they believe takes up the most space on bank balance sheets due to the size of the market. In 2016, the average daily trading turnover for interest rate futures was $5.046 trillion, nearly three times the daily turnover for interest rate swaps, and seven times that of foreign exchange forward contracts.

Specifically, the authors look at the “basis” between Treasury notes and futures contracts based on Treasury notes. Basis, in this case, refers to the difference between the implicit funding rate in the futures contract (which will account for balance sheet costs) and the financing rate for Treasury notes, also known as the “repo rate” (the implied interest rate on short-term, typically overnight, agreements to buy and sell government securities). This is roughly equivalent to the risk-free rate of borrowing since government securities are very safe assets against which to borrow. They refer to this difference as the “funding basis.”

The authors examine five-year Treasury note futures prices from 110 contracts whose quarterly expirations spanned the period between June 1991 and December 2018 and compare these to repo rate data for five-year Treasury notes over the same period. They find “a large positive funding basis” throughout the sample period, which averages 58.7 basis points. However, large swings in the funding basis occurred throughout this period. During financial crises or other anomalous periods, it hit highs of 200 basis points or more:

- Asian financial crisis in 1997: funding basis reached nearly 500 basis points

- Long-Term Capital Management hedge fund crisis in 1998: exceeded 500 basis points

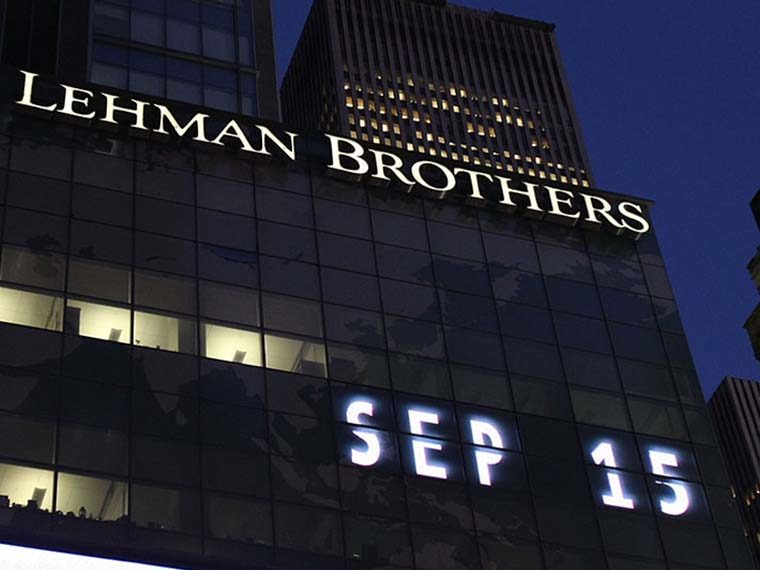

- During the financial crisis of 2008

The persistence of this gap and its presence well before the financial crisis suggest that increased regulation (via legislation such as the Dodd-Frank Act or international standards such as Basel Framework, which has been implemented in phases since the 1990s) is not the only factor making derivatives trading more expensive.

Overhang Costs a Major Factor Making Derivatives More Expensive

Rather, the authors identify debt overhang costs as a primary contributor to the funding basis before the financial crisis. After the financial crisis, the costs of capital regulation take over as the primary factor, but debt overhang costs remain a significant factor. And in fact, the funding basis is slightly larger during the pre-crisis period (58.79 basis points) compared with the post-crisis period (58.56 basis points.)

The authors break down the funding basis into four components: haircut, margin, debt overhang and residual capital regulation. The first two are negligible contributors, amounting to no more than around five or one basis points in the pre- and post-crisis period, respectively. However, capital regulation goes from an implied average net negative over the entirety of the pre-crisis period to accounting for 31.94 basis points out of the total 58.56 basis points in the post-crisis era.

Timing is another factor. The costs of balance sheet usage are particularly significant when that space is at a premium — specifically, at the end of the year, “as financial institutions face additional balance-sheet-related pressure to hold cash,” the authors note.

In sum, the consistent divergence of financing rates for securities and for the derivatives based on those securities highlights the role of financial intermediaries in asset pricing, and the various factors that make renting space on balance sheets more costly — namely how much debt overhang they face, and the amount of capital they are required to hold.

Featured Faculty

-

Francis Longstaff

Distinguished Professor of Finance; Allstate Chair in Insurance and Finance, Area Chair

About the Research

Fleckenstein, M., Longstaff, F. (2020) Renting Balance Sheet Space: Intermediary Balance Sheet Rental Costs and the Valuation of Derivatives. The Review of Financial Studies. 33(11), 5051-5091. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhaa033