Valentin Haddad’s research looks at the phenomenon of “information aversion,” when individual investors stop tracking their portfolios for fear of bad news

Ostriches don’t really bury their heads in the sand to avoid danger. But some humans do a version of that when it comes to their savings and investments: they become too afraid to look at their account statements.

Research by Marianne Andries of the Toulouse School of Economics and UCLA Anderson’s Valentin Haddad delves into the psychology of what the authors deem “information aversion” — and how investors might overcome it.

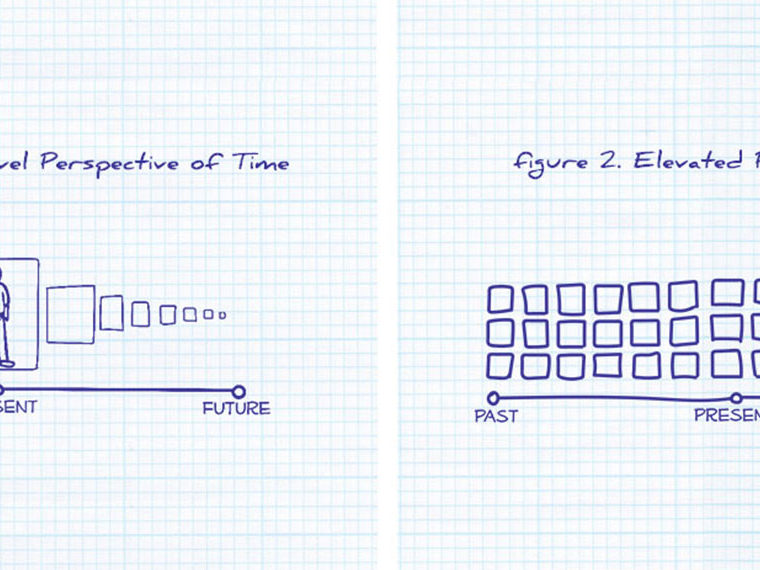

Their working paper, building on previous research by other academics, posits that many individuals over time become more sensitive to negative news about their investments and less appreciative of good news. In an interview, Haddad said a simple way to think about this emotional imbalance is that “every time you see things go up you’re a little bit happy, but when you see things go down you’re very sad.” So to avoid disappointment it becomes easier to stop looking at your accounts, or to look only infrequently. The overarching desire is “to stay away from information,” the paper says.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

The authors cite prior studies showing that the most risk-averse investors also are the most likely to fear checking the health of their nest egg. A 2012 study of Italian investors found that those who sought “a very high return” and tolerated “very high risk of losing money” observed their portfolios 3.9 times per year, on average. By contrast, those who sought just “moderate return and moderate risk” looked only 1.6 times per year — which seems counterintuitive if you want to be sure your portfolio risk level is remaining moderate.

The paper also notes that investor inattention “is more pronounced … in periods of low or volatile stock prices.” The authors include data from a study that charted account logins by investors who had 401(k)s at mutual fund giant Vanguard Group during the 2007–08 stock market plunge. As markets continued to fall, so did login activity.

Of course, some investors might argue that they’re just following the advice of investing gurus (like Warren Buffett, for one) who encourage patiently holding stocks for the long term. But Andries and Haddad make the case that calculated inattention by individuals “leads to missed financial opportunities.” After all, Buffett invests for the long haul but also pays attention to short-term volatility because that’s when bargains suddenly can appear.

If the idea, then, is to shake off peoples’ fear of checking their investments, how best to do it? The authors suggest that many investors could be encouraged to re-engage with their accounts if they received “alerts” after sharp market downturns. Such alerts would be “natural” for a bank, brokerage or mutual fund to provide via automated text messages or emails, the paper says.

In an interview, Haddad said the alert might simply be a warning that an investor’s account had declined by a certain percentage. Some people could be panicked by such notices but, ideally, the sender could make the point that it is providing a “backstop” to ensure investors have time to evaluate whether they want or need to make portfolio changes, Haddad said.

Although buy-and-hold can be a worthy strategy, “completely closing your eyes is dangerous,” Haddad said. “I like to think about a 50-year-old who has accumulated a lot of money in his/her 401(k), and the stock market drops by 30 percent,” he said. Because there’s no way to know if the market will drop far more, or how long it will take to recoup its losses, it may make sense for the investor to shift his or her portfolio, lifestyle or both at that point, rather than roll the dice “and just see what happens at retirement,” he said.

Featured Faculty

-

Valentin Haddad

Associate Professor of Finance

About the Research

Andries, M., & Haddad, V. (2017). Information aversion.