Forced sale of assets could stretch illiquidity across industries

The full extent of the risks in financial markets is often not apparent until a major crisis occurs. Only then is the true extent of global interdependencies revealed. And only then are the financial engineers’ bulwarks against risks truly tested.

A working paper by UCLA Anderson’s Shohini Kundu uses an unexpected global event — an oil price plunge in June 2014-16 — to trace its far-reaching repercussions in financial markets and the economy, and examine how it was in part transmitted through a surprising channel.

A plunge in oil prices has some predictable fallout: Oil company shares typically decline, so do the stocks of drilling rig operators and equipment manufacturers, as oil producing companies cut back on oil field activity. This can cause the oil companies to fall behind on interest and principal payments, leading to financial distress. The oil and gas price plunge of 2014-2016 was one of the three largest declines since World War II.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

Built-In Risk Containment

Kundu has been studying collateralized loan obligations. These are financial instruments that manage a portfolio of leveraged loans — loans to companies with high levels of debt or low credit ratings. CLOs have been disrupting the traditional lending market typically dominated by banks. In fact, CLOs fund as much as 75% of all new institutional leveraged loans. Given their significance in lending markets, Kundu investigates the risks associated with this growing source of finance.

CLOs have multiple tranches of loans with varying degrees of risk, as well as an equity tranche. CLOs are restricted by covenants to prevent excessive risk-taking and ensure that their managers have appropriate incentives for portfolio management.

To gauge these risks, Kundu had to identify the contents of CLOs. CreditFlux CLO-I Database was the primary source for the period from 2013 to 2015, enhanced with data from WRDS-Thomson-Reuters’ LPC DealScan and the WRDS Bond Returns. Additional sources were used to gather monthly equity returns, company characteristics, crude oil data and data about lines of credit.

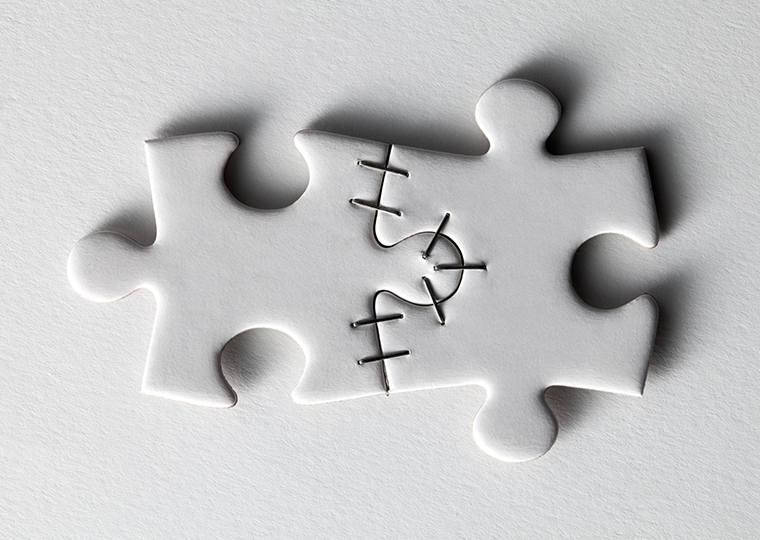

Kundu used the plunge in oil prices to take a look at how distress in one sector of the economy could propagate to other sectors through CLOs. She also wanted to understand the cause of the financial contagion. Kundu finds that the cause of the spread of the shock is the manager covenants, the provisions meant to protect investors. She suggests that these contract provisions can end up triggering fire sales of assets, causing negative consequences for asset prices across securities markets and the economy.

Shedding Assets to Manage Risk a Bad Bet?

Kundu demonstrates that fire sales are an unintended consequence of these covenants. In her findings, she discovers that an oil price shock, for example, could compel a CLO manager to sell loans in other industries such as retail at significantly reduced prices, leading to a contagion of distress spreading across different industries.

In Kundu’s study, CLOs with high exposure to oil and gas sector companies were pushed to their covenant thresholds when oil prices took a dive.

To understand why covenants incentivize fire sales, one needs to consider the pressure on a CLO manager to bring the portfolio risk back within thresholds assigned by a covenant after a shock has caused such a covenant violation. A quick way is for managers to sell the higher-risk loans in their portfolio, particularly those with market values higher than their accounting values in the portfolio. These loans will be sold off until portfolio risk is reduced enough that it is back within thresholds assigned by a covenant, while limiting further devaluation of the portfolio. Managers are choosing the loans to sell based on their market values — not based on any fundamentals that may be related to the oil and gas prices. The companies whose loans are chosen are simply innocent bystanders.

In Kundu’s study, CLOs with high exposure to companies in the oil and gas industry also had high exposure to the following industries:

- Health Care, Education and Child Care (~14%)

- Diversified Services (~7.5%)

- Retails Stores (~6.25%)

- Electronics (~6%)

As a result, the loans CLOs held in these industries were likely heavily sold, despite the fall in the oil price not having a direct impact on the companies.

Corporate loans tend to be illiquid, and fire sales can send prices into a tailspin. Not only do the market prices fall for companies whose loans were sold, but these companies, shut out from funding from CLOs and banks, also experience higher costs of capital when seeking future funding from any source. This results in the companies aggressively drawing down their credit lines for funding. Facing more expensive funding, companies may find proposed projects suddenly unattractive, and this may lead the firm to reduce R&D spending and cut down on hiring. These are all tough consequences for the misfortune of simply having your loans held in the same CLO portfolio as other companies facing sudden shocks.

By illustrating how covenants in CLO contracts can trigger fire sales, Kundu’s research provides an opportunity for policymakers and financial institutions to prepare strategies to counter these effects when future shocks occur.

Featured Faculty

-

Shohini Kundu

Assistant Professor of Finance

About the Research

Kundu, S. (2021). The externalities of fire sales: Evidence from collateralized loan obligations. Available at SSRN 3735645.