When they’re forced to pay up for deposits, it’s a bad sign for area’s economy

With the number of U.S. banks having plunged from 14,500 some 40 years ago to roughly 4,000 today, it’s no exaggeration to call the local bank an endangered species. Their prospects took another painful hit in early 2023, as the failures of two midsized banks — Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank — sent many customers of perfectly healthy banks scurrying to stash their money at the very largest deposit-taking institutions, J.P. Morgan Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo and Citibank, which collectively hold 35.3% of domestic deposits and are considered as too big to fail.

Being small, all of a sudden, was itself a problem.

Before consigning local banks to the financial dustbin, however, it might be worth appreciating their virtues, which include lending to the quirky mix of local businesses that national banking behemoths often ignore, and their continuing focus on customer relationships. Add to those something unearthed by Imperial College London’s Rajkamal Iyer, UCLA Anderson’s Shohini Kundu and Durham University’s Nikos Paltalidis: Observing deposit rates offered at local banks offers a surprisingly strong glimpse into future economic conditions in the area.

In a working paper, the researchers find that when banks that operate in a single state substantially increase the interest rate offered on deposits — the one-year certificate of deposit is the researchers’ bogey — in a given county, the odds of there being a county-level recession on the horizon increases significantly.

Paying Up Because Local Deposits Are Scarcer

The researchers present a straightforward hypothesis for how rising CD rates can be a real-time indicator of impending economic distress. When local businesses and consumers are feeling a pinch — business is down, layoffs are up, gig work is iffier — it follows that less money gets parked at a bank. (National banks, unlike local ones, simply move cash between locations.) As the local bank begins to watch its deposit growth stall out, it begins to sweat its ability to keep its balance sheet in line with lending needs and capital requirements. To deal with this liquidity crunch, a bank increases the rate on its CDs as an enticement to draw in much needed deposits.

“An increase in deposit rates can serve as a predictive signal for an impending economic contraction,” the researchers write.

Key features of the CD market drive the predictive value of this downturn detector. Rates are available in real time, unlike many economic indicators that have lengthy reporting lags. They also can signal a bank’s outlook; when deposit growth slows — necessitating raising rates — a bank will often pull back on lending to ease liquidity pressures.

Building a Deposits-and-Recession Database

The researchers utilize a database of one-year CD rates with a value of at least $10,000 — the most popular savings vehicle — offered by thousands of single-state banks between 2001 and 2020. Unlike recession-prediction research that looks at national data, a distinguisher of this study is its focus on local conditions.

Iyer, Kundu and Paltalidis studied CD rate changes among banks in nearly 2,900 distinct counties; there were on average three to four banks per county. They then compared the level of change for the average CD rate at the county level to changes in local GDP growth. They defined a recession as any year-over-year decline of at least 2% in county-level GDP.

Iyer, Kundu and Paltalidis find that in counties where the average CD rate increased by 1.3 percentage points on top of the average interest paid across the entire period of 1.63%, the likelihood of a recession one year ahead was 16% higher. The likelihood of a recession two years ahead rose by more than 37%. The likelihood of a recession three years ahead rose by nearly 33%.

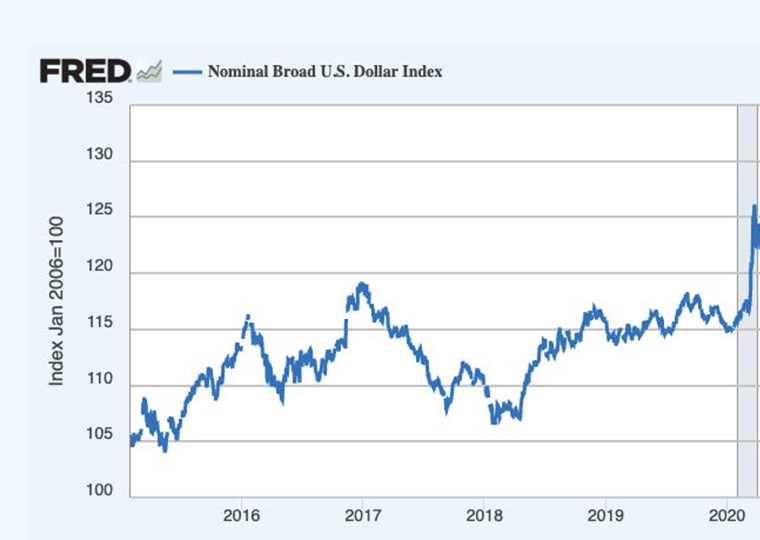

The predictive power of rising deposit rates was even stronger between 2010-2015, a period when the Fed stuck with its zero-rate policy, which suggests that the relationship between rising CD rates and GDP growth is not driven by changes in monetary policy.

As a further proof of concept for their deposit-rate recession indicator, the researchers also found that a marked increase in deposit rates accompanied two warning signals of economic slowdown: lower business formation rates and increased mortgage delinquencies.

The Great Recession that began in 2008 also provided a vivid opportunity to further explore their theory. The bar charts below sort deposit rates into quintiles at the county and state level in 2006; the counties/states with the highest CD rates in 2006 (the far right bars) were indeed at greater risk of a recession in 2008.

This research also illuminates the potential value of taking a more localized approach to studying, and addressing, economic stress.

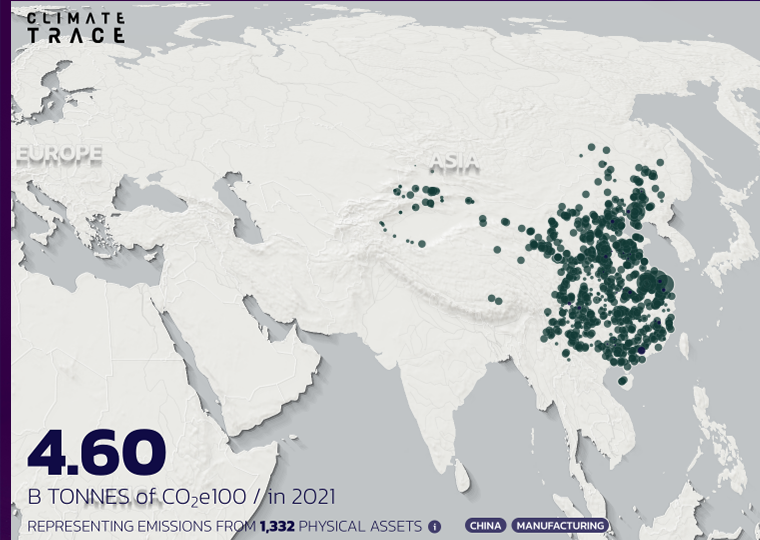

The Fed’s Open Market Committee largely focuses on national data such as inflation, the yield curve — and bond spreads in general — when debating its target for the federal funds rate. But as the map below shows, if you’re tracking rising CD rates as a signal of potential economic distress, the story is far more local: The counties with the highest rates are in the darkest shades of blue. Moreover, deposit rates offer a different lens to look for stress: Bond spreads and yields may be helpful in trying to forecast downturns caused by credit booms/bust but aren’t going to be as useful for detecting impending recessions not caused by credit stress.

And national metric watching, or relying on the financial health of the four too-big-to-fail banks, seems to whiff on stress in smaller markets.

At summer 2023’s Jackson Hole Economic Symposium, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell likened policymaking to “navigating by the stars under cloudy skies.”

This research suggests a publicly available, real-time data point can provide some clarity on a topic of key concern.

“There has been very little empirical work that focuses on measuring economic risks at the local level,” the authors write. “Our results suggest that a simple model that uses bank deposit rates has power to predict regional economic and financial risks with a high degree of accuracy.”

Featured Faculty

-

Shohini Kundu

Assistant Professor of Finance

About the Research

Iyer, R., Kundu, S., Paltalidis, N. (2023). Canary in the Coal Mine: Bank Liquidity Shortages and Local Economic Activity.