As major central banks adopt digital currency, emerging countries will feel mixed effects

Digital forms of dollars, euros and other major currencies are likely to be made legal tender before the end of the decade, allowing anyone with or without a bank account to spend them. Unlike cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin or ethereum, central bank digital currency will be backed and regulated by some of the world’s most stable institutions.

The new currencies could halve the costs of cross-border transactions and reduce fulfillment time from days to seconds, according to a pilot program studied by the Bank of International Settlements. For people who do not bank — some 14 million in the U.S., or 1.7 billion worldwide, according to the think tank Atlantic Council — CBDCs provide an alternative to high-cost check cashing and money transfer services.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

But for emerging countries, these new currencies from stronger economies create more ambiguous consequences, UCLA Anderson’s Sebastian Edwards writes in a working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research. Although their citizens will find it cheaper and faster to send much needed money home from foreign jobs, CBDCs could reduce financial stability in emerging countries and cut down an important source of revenue, Edwards says.

Not All Economies Would Benefit the Same from CBDC

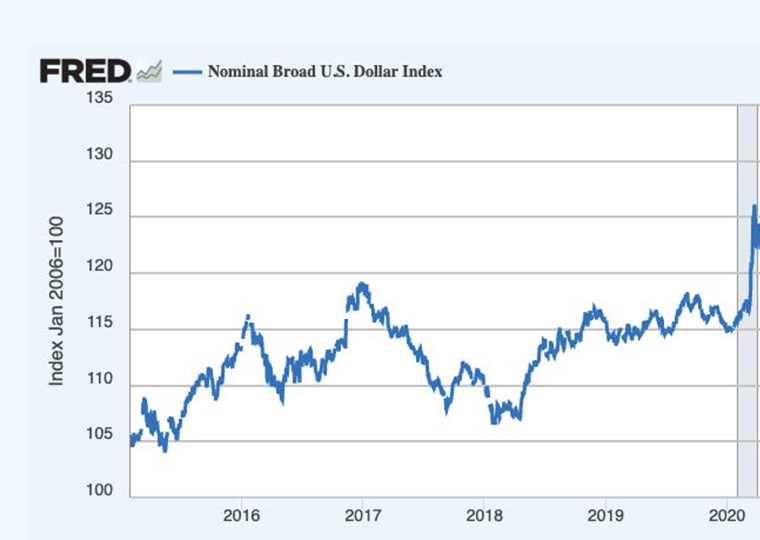

The key threat for emerging countries centers on the ease at which locals could adopt digital currency from an outside central bank and reduce their reliance on the local tender, Edwards says. Currency substitution, called “dollarization” when it involves U.S. money, would be particularly appealing to locals in countries with high inflation or recurring currency crises.

As substitution grows, the local currency depreciates, making it worth less for acquiring foreign currency, digital or otherwise, or for servicing foreign debts or buying foreign goods, Edwards explains. Local monetary policy, often aimed at controlling inflation, becomes less effective as foreign CBDC popularity grows.

What’s more, governments generally profit from producing and issuing their own currency, so seeing less of it in circulation would be a problem. The value of a piece of currency — say, a $10 bill — minus the cost to produce it is known as seigniorage.

Collections on seigniorage, currently as high as 1% of GDP in some emerging countries, fall sharply as the amount of domestic money as a percent of local GDP declines, Edwards writes. At times, seigniorage collections have been 13% to 50% of public revenues in countries like Argentina, Peru, Columbia and Ecuador, the study notes.

Cryptocurrency More Popular With People Than Governments

Unlike cryptocurrency, digital currencies issued by dominant central banks are unlikely to attract investors. The banks are considering measures like low limits on individual holdings or very high taxes on excesses to discourage anything but transactional use.

Details about rollout plans still under debate could have unanticipated effects on emerging countries, Edwards writes.

Citizens of emerging countries, on the other hand, seem already sold on digital currency generally. Some $76 billion in remittances went from the U.S. to people in foreign countries last year requiring fees of at least $3.5 billion, according to research by analytics company PYMTS.com and Stellar Development Foundation. About 23%, or 8 million people, surveyed already use cryptocurrency for these transactions.

Featured Faculty

-

Sebastian Edwards

Professor of Global Economics and Management; Henry Ford II Chair in International Management

About the Research

Griffoli, T.M., Peria, M.S.M., Agur, I. Ari, A., Kiff, J., Popescu, A. and Rochon, C. (2018) Casting Light on Central Bank Currencies. IMF Staff Discussion Notes, International Monetary Fund.

Edwards, S. (2021). Central Bank Digital Currencies and the Emerging Markets: The Currency Substitution Challenge.