Analysis also suggests a more rapid economic recovery by keeping workers and employers allied

Using public funds to make payroll for employers struggling through coronavirus restrictions ultimately may cost society less than the losses in earnings capacity and life years from unemployment, according to an analysis by UCLA economist Till von Wachter. Keeping employees paid and attached to their jobs, even while they’re not working, could help stave off the more expensive short- and long-term fallout from layoffs and joblessness, von Wachter explains in a new working paper.

The cost analysis comes amid increasing advocacy in the U.S. for an alternative to the traditional pattern of layoffs and unemployment assistance, followed by months or years of workers’ putting careers back together. In Germany, the approach is called Kurzarbeit, and it helped buoy the German economy during the financial crisis that began in 2008, and also helped the country recover more quickly.

Von Wachter’s paper, formatted as a proposal, aims to prevent losses in income, life expectancy and family stability that can plague recession-affected workers — and tax social services budgets — decades after the economy improves. Under the plan, millions of workers would be on standby for their employers rather than get laid off and try to compete for a very limited number of new jobs. And companies could quickly restart as coronavirus restrictions were lifted.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

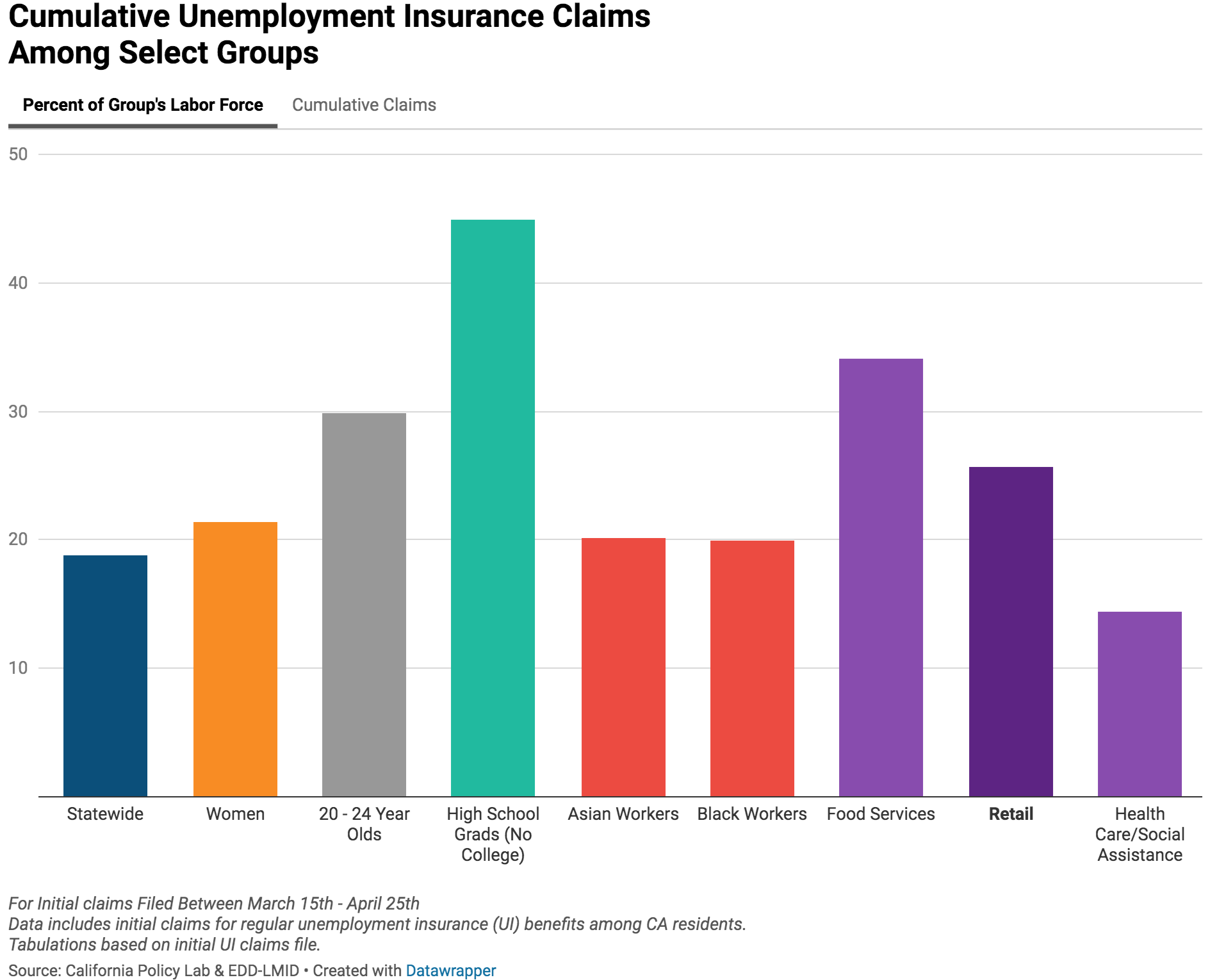

“Keeping workers attached to their jobs is now more important than ever,” says von Wachter. “In a recent analysis of job losers filing for unemployment insurance benefits in California, a record 90% expected to be recalled to their prior employer (versus about half during more normal times).” A large fraction of unemployed workers U.S.-wide has reported they think their layoffs are temporary. “Short-Time Compensation can be used to rehire workers, if at fewer hours, who were previously laid off, while the unemployment insurance system helps to subsidize their income. That way, employers can spread available work among a larger number of employees.”

In the post-World War II era, U.S. employers generally have been laying off workers earlier in each successive recession and hiring them back later and in fewer numbers. Thus, without a national workshare program in place, and without employers’ being well acquainted with state workshare programs, it’s difficult to prevent massive unemployment in a downturn or during a crisis. The U.S., too, has a history of concocting economic and financial rescue packages at the last minute, rather than planning ahead for trouble, which makes the programs difficult to administer and hard to measure.

The CARES Act, the emergency relief package Congress passed on March 26, 2020, includes funding for several strategies aimed at holding employees “in place” and avoiding massive layoffs. This includes funding for so-called Short-Time Compensation programs (also called the Work Sharing Program), funding for short-term loans for small businesses (the so-called Paycheck Protection Program), and tax subsidies to help firms cover payroll and to cover funding for partial unemployment insurance benefits that employees, whose hours have been reduced, can access.

The most discussed program funded by the CARES Act, aimed at businesses with fewer than 500 employees, is the new Paycheck Protection Program. It helps cover two months of payroll and some other expenses, like the business’ rent, via forgivable loans. The relief is designed to help tens of thousands of businesses stay afloat amid stay-at-home orders, mandated across the country to tamp down the spread of coronavirus.

The CARES Act also pays 100% for a state’s existing Short-Time Compensation or the Work Sharing Program, and 50% for those states that institute a new such program. Short-Time Compensation programs help employers to avoid layoffs of a subset of their workers by allowing them to instead reduce hours of all workers. Workers then receive prorated unemployment insurance benefits from the state. Under CARES, not only do states get a substantial subsidy for paying these benefits — which is sorely needed given the hit of Covid-19 on state budgets — but workers get an additional $600 per week, irrespective of their prior earnings or the number of hours they work.

The catch is that states must organize their own programs to hand out the federal funds, and none has experience with workshare on such a large scale. Banks around the country are worried about overwhelming demand. Although 26 states covering almost three-quarters of the workforce have some form of a workshare program in place, they are much more restrictive than the federal emergency rules, and not particularly popular with employers.

Much if not all of the original Paycheck Protection Program funds were committed. Some funds have been returned to the program after criticism that lenders favored borrowers Congress had not intended to help. And a second program is getting underway. Oversight and the ability to track use of the funds in real time to measure economic benefits appear lacking.

An advantage of work sharing, von Wachter says, is that 28 states have established programs. This allows funding to be effectively directed to employers and enables monitoring to make sure that workers, indeed, were not laid off.

Von Wachter’s working paper lays out the costs, benefits and logistics of expanding state workshare programs using available funds. The analysis acts as a how-to guide for states to mitigate massive unemployment with temporary payroll benefits. Layoffs have already been widespread, sending the nation’s official unemployment rate to 14.7%, the highest level since the Great Depression.

Costs for a country-wide workshare expansion are on par with combined state and federal government spending for unemployment benefits during the Great Recession, according to von Wachter’s calculations. His analysis includes discussion of how to divert money from existing benefits programs, such as unemployment insurance from states and emergency funds approved by Congress, for a revenue-neutral program.

The paper reiterates the lifetime of disadvantages common to workers who end up unemployed or who are trying to start careers during recession. Numerous studies, including von Wachter’s research with Northwestern University’s Hannes Schwandt, find that their wages were depressed throughout their careers, even among highly educated workers. Life expectancy also drops, with recession-affected workers likelier to die in middle age, especially of diseases associated with stress and drug and alcohol abuse, according to a working paper by Schwandt and von Wachter.

“The existing research makes clear that the outcome of the next few months will shape the long-term outcomes of millions of individuals directly affected by the crisis,” von Wachter writes. “The policy choices made today will have a significant effect on the mortality, earnings and socioeconomic outcomes of new labor market entrants and job-losers that will extend over the course of their lives.”

Cheaper than Unemployment

In the U.S. alone, many if not most businesses remain closed or severely curtailed by stay-at-home orders, despite a nascent and shaky movement to begin reopening the economy. Tens of thousands of bars haven’t collected revenue for a month or more, and restaurants across the nation are limited to take-out orders. More than 30 million workers have already made first-time unemployment benefit claims since public health restrictions started, and economists predict millions more layoffs before it’s over. The Federal Reserve Bank forecasts a peak of 30% unemployment later this year.

Unlike other struggling businesses that cut hours or jobs, employers in the Work Sharing Program continue to pay some fraction of payroll. Ultimately, fewer workers end up unemployed and in need of longer-term assistance. Their continuing paychecks and health benefits also keep down applications for food and medical assistance that typically spike during recessions.

Von Wachter estimates an expanded workshare plan would cost between $57 billion and $166 billion to cover wages for 10 million workers for one year. Costs are covered largely by turning state unemployment benefits into federally funded assistance. As a benchmark, in 2010, when unemployment last stood at 10% or higher, states and the federal government spent roughly $160 billion on unemployment compensation. The amounts required are substantially lower than the funding currently allocated by the CARES Act for short-term business loans.

Losing a job during a recession reduces life expectancy by about 1.5 years, von Wachter finds. Even if not affected by such an extreme outcome like death, workers who lost stable jobs in past recessions have suffered long-term earnings losses of 20%. If only 10 million of the current more than 30 million unemployment insurance claimants suffer earnings and health losses like some of the job losers in past recessions, it is likely to cost affected workers some $1.25 trillion in earnings capacity and 15 million life years, he finds.

Lessons from the Great Recession

The U.S. federal government offered to pay for greatly expanded workshare programs in the aftermath of the recent Great Recession, but there were few takers among employers.

Von Wachter’s research calls for removing restrictions and rules that have discouraged U.S. employers and workers from taking workshare offers in the past. Typically, for example, employers can’t reduce workforce hours more than 60%. Programs in some states are even more restrictive.

Today’s Work Sharing Program could cover up to 100% of lost hours and wages (wages for the bar that’s not open now, for example) using the expanded unemployment benefits approved by Congress.

Eliminating potential penalties for tapping Work Sharing Program funds also can increase uptake, according to von Wachter’s paper. Typically, employers who lay off workers see their payroll tax increase to help the state fund the cost of paying unemployment insurance benefits. Since the federal government pays for Work Sharing Program benefits, this is not necessary. Hence, states should commit not to raise firms’ payroll taxes as a result of using the program. This would make workshare programs more attractive than layoffs. Similarly, workshare benefits should not lower the amount of unemployment benefits a worker could collect if she’s laid off after the crisis.

Von Wachter’s working paper addresses many scenarios for funding and structuring workshare and unemployment programs during and after the pandemic. It also details how unemployment data can be used to monitor the labor market in real time and adjust policies accordingly.

The Work Sharing Program “effectively puts the workforce on standby until the COVID-19 outbreak is contained,” von Wachter writes. Employers “maintain knowledge and skills specific to job relationships, and avoid the costs of a massive turnover of the workforce that could result from large-scale unemployment.”

Featured Faculty

-

Till von Wachter

Professor of Economics

About the Research

Von Wachter, T. (2020). The long-term effects of the COVID-19 crisis on workers: How scaling up the workforce system can help.

Schwandt, H., & von Wachter, T. (2019). Unlucky cohorts: Estimating the long-term effects of entering the labor market in a recession in large cross-sectional data sets. Journal of Labor Economics, 3(S1), S161–S198.

Schwandt, H., & von Wachter, T. (2019). Socioeconomic decline and death: Midlife impacts of graduating in a recession.