Valentin Haddad’s research finds that insurers’ patient investing shields risky assets — and those who hold them — from steeper declines

Life insurance companies provide peace of mind for millions of families worldwide. Less appreciated is that they also play a protective role for financial markets.

By patiently holding trillions of dollars’ worth of bonds and stocks to pay for future claims, insurance companies function as “asset insulators” that shield the value of those securities from the full brunt of market turmoil, according to a working paper by Gabriel Chodorow-Reich of Harvard, Andra Ghent of the University of Wisconsin and UCLA Anderson’s Valentin Haddad.

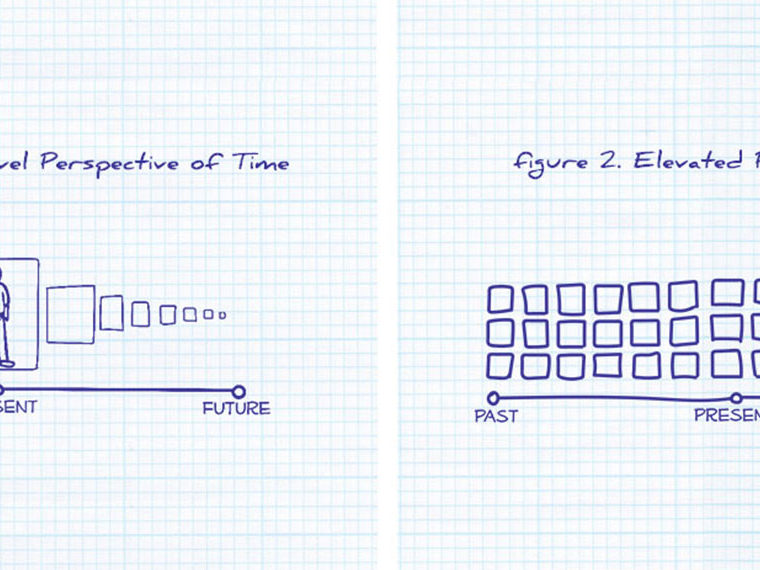

Amid normal market volatility, a $1 drop in the value of life insurers’ asset holdings will reduce the companies’ own equity market value by as little as 10 cents, the authors found. To put it another way, 90 percent of the decline in insurers’ asset holdings doesn’t “pass through” to the marketplace via a decline in the companies’ worth. Hence, the insulation concept.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

But the study also found that insurers’ asset-insulating function deteriorated sharply during the extreme market volatility of the 2008–2009 financial crisis. In that period, the pass-through of asset losses to insurers’ market values surged to roughly 1-to-1. If that level were prolonged in a future crisis, it could feed a downward spiral in markets if the companies were perceived as being at risk of failure and suddenly began dumping assets to boost liquidity.

The authors’ central proposition — that insurers add value to financial markets by virtue of their insulating role — contradicts the famous Modigliani-Miller theorem of 1958. Named for its authors, legendary economists Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller, the theorem basically regards individual financial institutions as irrelevant in terms of their net influence over markets. In other words, in the long run it doesn’t matter where assets are held.

But UCLA Anderson’s Haddad said in an interview that the study suggests “things could have been a lot worse” for markets leading up to the financial crisis and immediately after it, if not for how life insurers and other institutional investors sought to hold on to risky assets while other investors were dumping them.

Particularly important for markets was the makeup of big insurers’ portfolios as the crisis began, the study says. Despite the “commonly held view” that insurers largely hold low-risk assets such as Treasury bonds, the authors say, they found that the largest concentration of assets was in corporate bonds. And roughly half of those bonds were rated BBB or lower. The BBB rating is considered “lower medium grade” in quality, and is just two notches above the “junk” rating, meaning non-investment grade.

Because insurers invest for the longer term and only require cash (beyond operating costs) when claims are made, normal market fluctuations don’t trigger an urgency to sell higher-risk bonds. “Insurers hold securities for an average length of four years, a horizon long enough to allow the transitory fluctuations in market prices to dissipate,” the study says.

The research suggests that regulators face a conundrum in trying to guard against a repeat of the 2008–2009 financial crisis. After the near-failure of insurance titan American International Group in 2008, the federal government deemed some of AIG’s peers “systemically important financial institutions,” subject to special Federal Reserve oversight because of their size and potential risk to the financial system.

MetLife Inc., one of the giant insurers singled out, won a federal court case in 2016 to end Fed oversight, after calling it “regulatory overreach.” Now, expectations are that the government will exempt MetLife’s huge rival, Prudential Financial, from regulation as well.

In their study, Chodorow-Reich, Ghent and Haddad say that insurers’ “useful” role of asset-insulation could be upended if regulators sought to limit the companies’ holdings of higher-risk bonds. “Proposals to tightly regulate asset holdings might impair this function,” the authors write.

But they concede that limited regulation also could be hazardous, given how the pass-through of insurers’ bond losses to the companies’ market values spiked at the height of the last crisis. The danger is that “asset-insulation may be most fragile exactly when it is most valuable,” the paper says.

Featured Faculty

-

Valentin Haddad

Associate Professor of Finance

About the Research

Chodorow-Reich, G., Ghent, A., & Haddad, V. (2016). Asset insulators.