Civil War officers with working-class backgrounds held units together best

If you think we’ve left the Great Man school of history behind, pick up any popular business publication and notice how corporate performance — good and bad — seems wholly reliant on the brilliance or ineptitude of the CEO.

Apple still feels like an extension of the ego of Steve Jobs, even nine years after his death. And someone new to business might never guess that Warren Buffet is just one of more than 390,000 people employed at Berkshire Hathaway, as if the 90-year-old personally settles every Geico Insurance claim.

In truth, most organizations’ operations are broken down into small, discrete units, and results often vary widely among them based on the work of a lower-level manager. In retail, that might be the district manager, overseeing 6 to 12 stores. In education, the school principal weighs heavily on results. And in manufacturing, the plant manager’s performance determines the quality of goods and whether they’re shipped on time — or if the whole thing runs off the rails.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

The middle manager, by the way, is not only unsung, but is the perpetual target of private equity investors, consultants and others who advise cutting layers from companies and flattening organizations. The movement to rid organizations of middle management might suggest nobody should care what makes a good middle manager.

But UCLA Anderson’s Christian Dippel and University of Pittsburgh’s Andreas Ferrara, two economists who study history for insights, focus on the American Civil War and its low-level officers (who, of course, were managers) to see what traits made them succeed or fail.

Countless books have been written about the battlefield prowess of Civil War Generals Ulysses S. Grant, Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. But Dippel and Ferrara’s research suggests lesser acknowledged men played a decisive role in the northern states’ victory.

The battlefield performance of the Union Army provided an ideal setting for identifying leadership characteristics most critical to building cohesion and cooperation, particularly during times of stress.

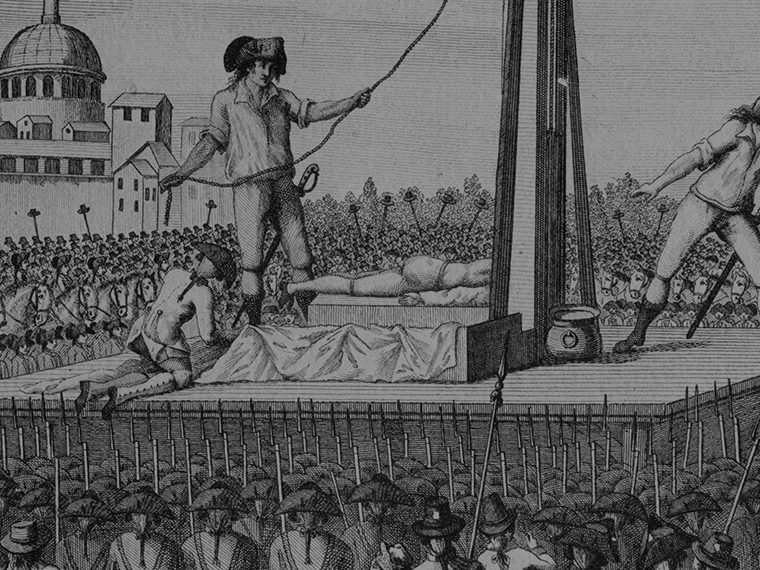

The Civil War, the struggle between Union and Confederate troops over slavery, sovereignty and secession, claimed the lives of an estimated 750,000 soldiers, more than all other U.S. wars combined.

Enlistment rates on both sides of the Civil War were extraordinarily high; 80% of men born between 1837 and 1845 eventually served in the war.

Since the army was largely made up of volunteers (94%), strong leadership was critical to maintaining morale and keeping soldiers from deserting.

Civil War military units were composed of friends and neighbors who were less likely to desert unless others did, the authors point out. And the horrific nature of the battles called for leaders whose virtues included a willingness to lead by sacrifice and example, and a sense of direction and resoluteness.

In their working paper, Dippel and Ferrara analyzed data from state and federal military records covering more than 2.2 million men in the Union Army. The army’s organization was similar to that of modern times, with a top-down command structure.

Organization charts typically start at the top, but Dippel and Ferrara look at them more like this:

- A company, with a captain in charge, was comprised two platoons, and each platoon usually had 20–50 soldiers, with a lieutenant at its head.

- 6–10 companies constituted a regiment, led by a colonel.

- 2–5 regiments made up a brigade, led by a brigadier general.

- Major generals led the units ascending above a regiment: division, corps and an army.

Dippel and Ferrara find that leadership effectiveness was most critical at the level of 100-men companies, which are closest to what social psychology researchers have identified as humans’ “primary group size,” and which most military historians have identified as the “effective fighting units at which cohesion could either crack or be sustained.” Higher-ranking officers like colonels and generals determined tactics and strategy, but had less impact on the cohesion of fighting units.

Within the universe of the Union Army, the authors identified 9,530 companies (comprising infantry, cavalry and artillery) that saw combat. Over the course of the war, the average company had 3.5 captains and, above that, four colonels.

Dippel and Ferrara created a database that allowed them to follow the commanding officers and their fighting units through the war. When possible for each commanding officer, they recorded age, whether the individual had enlisted as an officer (experience level), the number of promotions he was awarded over his career and his acts of valor, measured by medals of honor.

The researchers were able to link more than 900,000 Union Army soldiers to the 1860 full population census, which provided them information on soldiers’ and officers’ civilian occupations. Using the U.S. Census Bureau’s occupational rank (from 0 for unemployed/retired/student to 100 for professionals such as medical doctors), they coded whether a commander’s occupation was above or below the median occupation of the lower-level privates and corporals.

To determine which leadership characteristics had the greatest impact on group cohesion, they created a model correlating each of those leadership characteristics with the desertion rates of the units the captains and colonels commanded.

It was the older, more courageous and more experienced captains with working-class occupational backgrounds who were the most successful at maintaining cohesion.

Captains who came from more “socially detached professional backgrounds” with higher occupational rankings experienced a 7% higher desertion rate than the average. Courageous captains, those who were at one point awarded a medal of honor for bravery, consistently saw 12.8% fewer desertions in their companies; and those who were promoted or enlisted at an officer rank (an indicator of greater experience) experienced a 4.3% lower desertion rate.

There were no formal screening or entry exams in the Union Army. The vast majority of captains and lieutenants were selected by their fellow soldiers at the time of enlistment, according to research cited by the co-authors. Dippel and Ferrara believe this selection process may have led to greater trust and loyalty among the men they commanded, who often came from the same communities as their leaders.

It might also be that promotions at higher levels of leadership are “more patronage-based and less meritocratic,” the authors surmise. Another possibility is that those promotions were linked to management skills or military training that didn’t produce the same degree of loyalty among the lower ranks.

Over the course of the war, the average company lost close to eight soldiers to desertion and had more than 16 soldiers killed. Surprisingly, involvement in battles, minor or major, had a minimal impact on desertion rates, according to their data. Minor battles increased weekly desertions by just 1% while involvement in major battles boosted weekly desertions by close to 4%.

An analysis of the 20 deadliest battles of the war allows the authors to home in exactly on the days of those battles. The loss of a captain during the heat of battle had a serious impact on battlefield morale. The death of a captain during a battle increased the likelihood of desertion in that company during the same battle by two-thirds.

Could lower desertion rates be explained by a leader’s taking a more cautious approach to battle, which would not necessarily be good for the unit’s overall performance? To answer this question, Dippel and Ferrara used 122 maps held by the Civil War Preservation Trust to create geo-referenced dynamic battle maps pinpointing each regiment’s position on the battlefield during different battle phases. The average company participated in at least one major battle, and some were involved in up to five. Contrary to the “cautious leader hypothesis,” they find that the captains who were the most successful at keeping their troops cohesive also manned the front lines in battle. On the maps, they were closer to enemy lines during the heat of battle and likelier to be engaged in winning battles.

Featured Faculty

-

Christian Dippel

Assistant Professor of Economics

About the Research

Dippel, C., & Ferrara, A. (2020). O Captain! My Captain! Leadership and team cohesion in the Union Army.