That’s helpful information in a social media world filled with friends who do enviable things

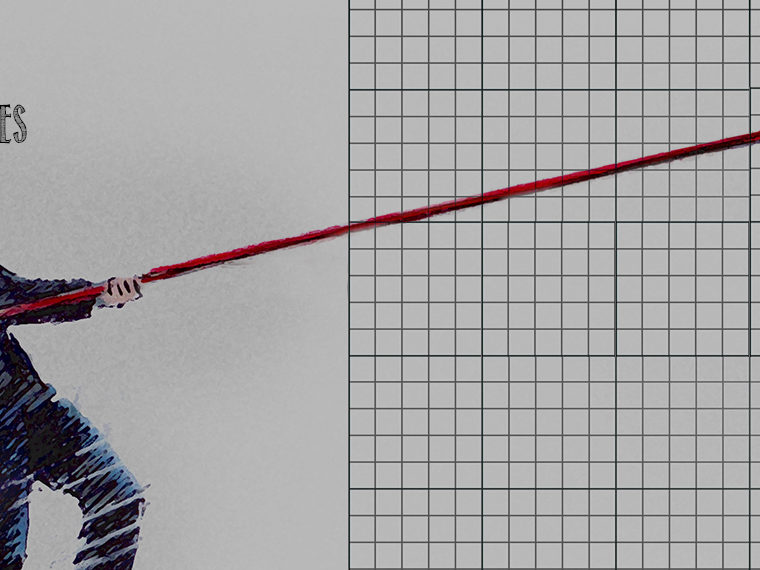

Valentine’s Day is a fertile Petri dish in which to study envy. Researchers recruited 100 participants each day during the month of February 2017 — 2,800 in all — and gauged their level of envy of a description of someone else’s having grand Valentine’s Day plans. As the graph below shows, envy was higher in the days leading up to February 14, and then cratered the day after the holiday.

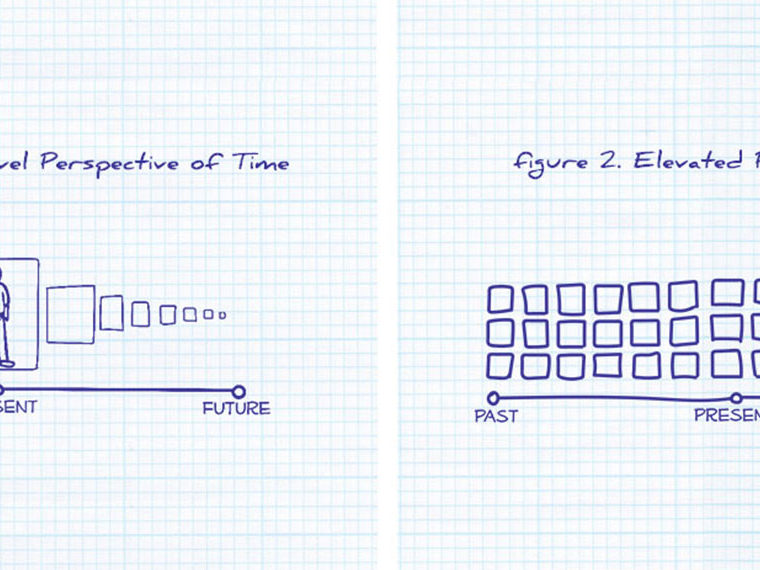

What gives? In theory, the intensity of our envy should be a function of how we feel about the person and about the event we’re not experiencing, irrespective of when it occurs.

But it turns out, how hard we fall into envy is time-sensitive.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

Across four experiments that tracked the feelings of nearly 5,000 participants, the University of Chicago’s Alexander C. Kristal and Ed O’Brien and UCLA Anderson’s Eugene M. Caruso established that our pangs of envy are higher when we read about or see someone who is planning to do something we covet. We are less envious if the event has already occurred.

As the researchers explain in a paper published in the journal Psychological Science, using the realm of vacations, we will envy the officemate who has made plans for a trip to Maui more than the officemate who has already taken the exact same trip to Maui.

In one experiment, more than 600 participants were asked to focus on a real-life friend and imagine said friend experiencing five events that the participant would consider dream worthy: the participant’s dream vacation, the participant’s dream date, getting promoted to the participant’s dream job, moving into the participant’s dream home and buying the participant’s dream car.

Half of the participants were primed to think about all five events as having already occurred and the other half were told to think about these scenarios as something that would happen in the future.

The researchers then had the participants rate various measures of their envy and jealousy on a scale of 1 (not feeling it at all) to 7 (feeling it very much). Those considering events in the past had lower levels of envy than those tasked with imagining events yet to happen.

In another experiment, Kristal, O’Brien and Caruso explored whether timing sensitivity was dependent on the nature of the envy as malicious (it makes the person feel frustrated and angry) or benign (the envy inspires the person to want to do what it takes to have that experience, too).

Participants sorted into the malicious pool had an envy score of 3.57 for an event that was still in the future. The same group’s score dropped to 2.86 for an event that had already happened. But the inspiration factor for the benign envy group did not change with the “timing” of the enviable event.

“The passing of time may especially assuage the destructive pain of comparison (as opposed to its more motivating, inspiring feelings, which may remain high or even grow more intense after other people achieve a superior outcome),” the authors write.

For anyone interested in moderating envy, or having a better coping mechanism, the research suggests that literally giving it time to pass can help. In a study that tracked 322 participants, an envy-inducing event became less enviable if contemplated through the prism of having happened a year ago.

The study participants were asked to think of a friend, classmate or family member who had an upcoming enviable event. Once again, everyone was run through questions that established their level of envy.

Then the participants were sorted into three scenarios for a second run through the same questions. A control group simply completed the same questions again. Another group was asked to “fast forward” to about a year from now and consider how this event would feel when viewed as having happened in their past. The “future” group was asked to dial back about a year and register how they felt when the event had yet to occur. All participants were prompted to then switch back to considering their feelings in the here and now.

Both the future and past groups experienced a drop in envy, but the decline was bigger for participants who focused on the event as having already happened.

Similar patterns persisted in how participants experienced stress and self-esteem. And the “past” group reported a higher level of life satisfaction than the participants primed to think about how they felt prior to the event’s occurring.

“There is something of a paradox in our reactions to people who get to have what we want: It stings less if they already have it,” write the authors.

Featured Faculty

-

Eugene Caruso

Professor of Management and Organizations and Behavioral Decision Making, Bing (’86) and Alice Liu Yang Endowed Term Chair in Teaching Excellence, Faculty Co-Director, Inclusive Ethics Initiative

About the Research

Kristal, A.C., O’Brien, E., & Caruso, E.M. (2019). Yesterday’s news: A temporal discontinuity in the sting of inferiority. Psychological Science. doi: 10.1177/0956797619839689