“Uh, I already bought a house”: Tech workers spend ahead of actual stock sales

Here’s a tip for San Franciscans hoping to list homes for sale just as a wave of initial public offerings floods the market with millionaires: Don’t wait too long. New research suggests that the newly rich from Uber, Pinterest, Lyft, Airbnb and other upcoming IPOs will start spending windfalls months before they collect the cash.

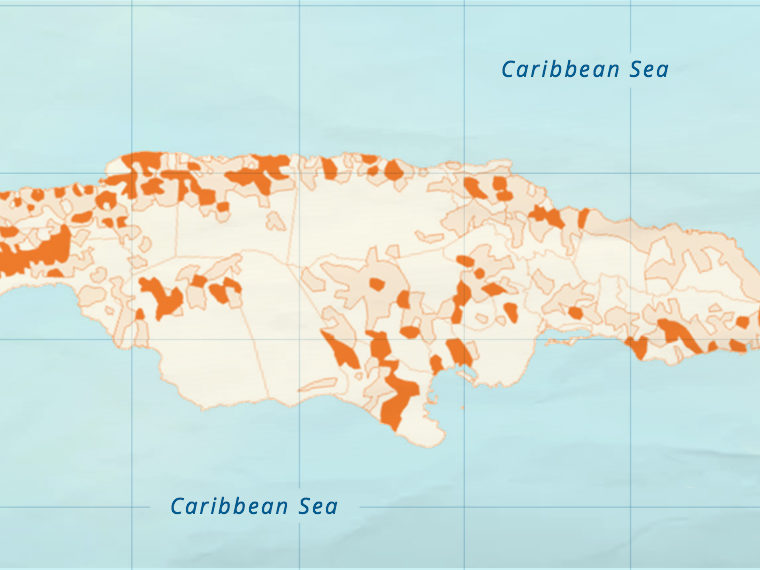

In a study that covers 720 California IPOs from 1993 through 2017, researchers found significant increases in average home sale prices in neighborhoods near companies going public.

But the timing of those gains doesn’t coincide directly with payouts to employees. Shareholding employees seem not to need cash in hand to spend expected IPO proceeds, according to the working paper by UCLA Anderson’s Barney Hartman-Glaser and Pennsylvania State University’s Mark Thibodeau and Jiro Yoshida.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

The largest price increases occur in the weeks and months following a company’s S-1 filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission, which declares its intention to publicly list shares. Although the S-1 signals that an offering is imminent, there’s no public market into which employees can sell their shares yet. The first public trading day is not specified and typically will be months away.

Nevertheless, the study finds, home prices rose an average 3.3 percent, 1.7 percent and 1.3 percent within a 1-, 5- and 10-mile radius, respectively, in the period between the S-1 filing and the first trade.

Home prices rise further still between the first trading day and the next six months, according to the findings. This, too, is generally a period when employees cannot cash out their shares because lock-up periods prevent them from selling in the first 180 days of public trading. This active trading, however, makes clearer the true value of employee holdings. Home prices rose an average 2.2 percent, 1.3 percent and 1.6 percent for the 1-, 5- and 10-mile radiuses during this period, according to the study.

Home prices change very little at the end of the lock-up period, when most employees can finally get real cash for their shares. The study revealed price rises following lock-up events at 0.1 percent, 1.4 percent and 0.8 percent in the three zones surveyed.

The findings suggest that original shareholders start shopping for homes when the S-1 signals that their liquid wealth is about to increase, not when it actually does. Banks in California, where startup companies cluster and IPO wealth is most common, may be particularly comfortable relaxing lending standards for these employees, note the authors.

California — the San Francisco Bay area in particular — is expected to see billions more in luxury spending this year as a rash of famous startups prepare offerings that will turn many employees into overnight millionaires. Those who make a living selling high-end goods, from yachts to private jet services, are already pitching the IPO crowd, and homeowners are trying to time their listings for optimal exposure.

Many of these newly targeted customers are well paid but not wealthy yet. Financial data typically needed for penthouse buying, such as the exact amount of money that will land in the bank account and when, is still unavailable to most of them. But in the frenzy of IPO anticipation, it appears a lot of deals can close well before such mundane details are settled.

Featured Faculty

-

Barney Hartman-Glaser

Associate Professor of Finance

About the Research

Hartman-Glaser, B., Thibodeau, M., & Yoshida, J. (2018). Cash to spend: IPO wealth and house prices.