The goal is continued development of new drugs and reduction of often shocking prices

Spinal muscular atrophy, or SMA, is the most common genetic cause of death in childhood. It affects at least 10,000 children and adults in the U.S., and about one in 8,000 people worldwide.

SMA is one of the more than 7,000 maladies classified as a “rare disease,” defined in the U.S. as one that affects fewer than 200,000 patients. (The European Union has a slightly different definition.) While individual disorders may affect only a few thousand people, all together, more than 350 million people globally suffer from rare diseases.

Only 500 of the maladies have available treatments.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

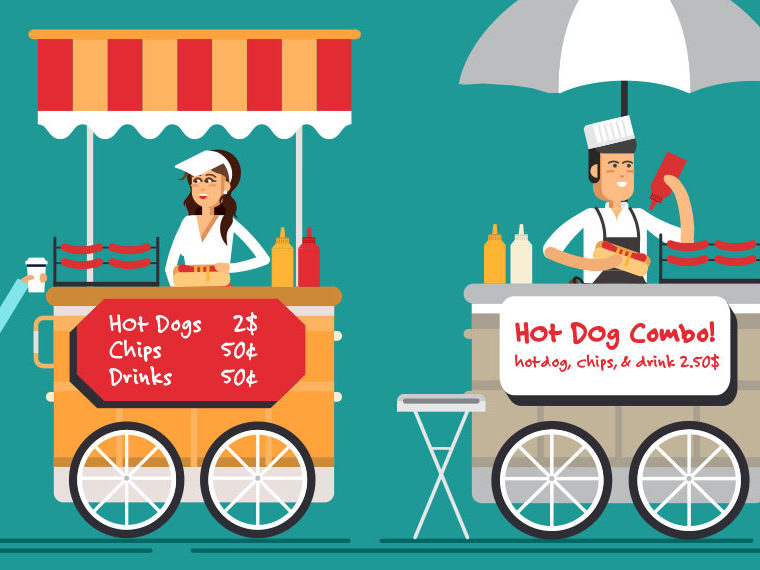

The problem for pharmaceutical companies is that research-and-development costs of “orphan drugs” (drugs that go undeveloped because they aren’t projected to be profitable) can be just as great as those used for treating diseases with tens of millions of cases. But the potential market for orphans is many times smaller. So drugmakers have been slow to invest in treatments for rare diseases. Patients, by the same token, often have to pay exorbitant prices for the drugs.

Under pressure from patient advocates, policymakers have devised a variety of tactics — including R&D subsidies, payment arrangements and price-setting mechanisms — to make orphan drugs more available and affordable. But each comes with tradeoffs, and there’s no consensus about which ones work best.

In a working paper, Eindhoven University of Technology’s Wendy Olsder and Tugce Martagan and UCLA Anderson’s Christopher Tang analyze the policy options to find which of them deliver the greatest benefit, both to patients and to drugmakers.

Their findings suggest that to maximize patient welfare — whereby new drugs are both available and affordable — the best approach may be to have the price of orphan drugs set by an outside group made up of doctors, patient advocates and policymakers, not by the manufacturer. Such a policy, already used by several European countries, affords patients lower costs, while manufacturers still receive attractive profits and governments can provide subsidies to both patients and drugmakers without causing prices to rise.

“Orphan-drug subsidy programs are controversial,” the authors write. “Although they stimulated the R&D of new treatments, they did not necessarily improve patient access to these drugs.” Combined with a program that turns over price setting to an outside group, subsidies could be more equitable, the paper suggests.

In 1983, the U.S. adopted the Orphan Drug Act to encourage the development of treatments for such rare diseases as SMA, Huntington’s and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease). The law promises speedier approval for effective orphan drugs and gives manufacturers exclusive rights to market the drugs for seven years, a 50% tax credit on R&D costs, and $30 million in grants for clinical trials. In the 34 years between its passage and 2017, the act was credited with the creation of 575 approved treatments. (The European Union followed suit in 2000 with its own program to encourage development of Orphan Medicinal Products.)

Spinraza, a treatment for SMA, was granted orphan drug status under the act and approved by the FDA in 2016. Sold by Biogen, a Cambridge, Massachusetts, biotech company, Spinraza is one of the most expensive drugs on the market, costing $750,000 for the first year of treatment and $375,000 per year after that. Some insurers cover the treatments for some SMA types, but not for all.

Consortium-based price setting is seen as one way to address the high cost of orphan drugs. In 2018, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Austria and Ireland created an independent consortium known as the BeNeLuxA initiative and reached an agreement with Biogen on the price of Spinraza in their countries. The agreed-upon price was not disclosed (though one report suggests the nations negotiated a 22% discount in first-year treatment price). The Dutch health minister said it had been reduced “to an acceptable level.” Similar initiatives have been adopted by countries in Scandinavia and southern Europe.

Many advocates see “outcome-based” payment programs (also known as “No Cure, No Pay”) as an attractive way to smooth access to orphan drugs. In a Netherlands pilot begun in 2019, Bristol-Myers Squibb agreed to provide its immunotherapy medication nivolumab (marketed as Opdivo) to patients with a rare form of cancer for 16 weeks, and the company will be reimbursed only if the treatment is effective.

The policies have their critics: Some worry that the lower consortium-set prices may be a disincentive for drugmakers’ R&D efforts. Insurers and others fear that outcome-based payments can lead to higher drug prices.

To unpack the effects of the different policies, the researchers developed a game-theory model to identify the best balance of patient welfare and manufacturers’ returns. Among their findings:

- If manufacturers set the price, subsidies to either the drugmaker or to patients can result in higher costs, but subsidies to patients will have a bigger impact on cost. The best policy in this case is to grant subsidies to manufacturers only, which gives them an incentive to produce more effective drugs and indirectly leaves patients better off.

- Having an outside group like the BeNeLuxA initiative set prices means significantly lower costs for patients but it could still deliver an attractive profit to manufacturers. In this case, subsidies can be paid to both manufacturers and patients. If the set price is high, manufacturer subsidies can be lower, but patients would need more assistance. If the selling price is low, the opposite is true.

- Outcome-based payment programs can result in high drug prices whether they’re set by the manufacturer or an outside group, especially if subsidies are low. If subsidies are high enough, though, the government absorbs more of the costs of successful treatment.

The case of Spinraza, the SMA treatment, illustrates these effects. Using the industry average for the cost of developing new drugs (Spinraza’s actual R&D cost is unknown) and some assumptions, the researchers estimated that having an outside consortium set the price would improve total patient welfare by 62%. Biogen’s profits for the drug would be 15% lower than if it set the price itself, and total welfare (for both patients and the drug company) would be 8% higher.

“By delegating the pricing decision to an independent consortium,” the authors write, “the government can achieve a higher social welfare with a lower price and continue to provide an attractive environment for the manufacturer.”

Higher subsidies, they note, would mean an even bigger increase in patient welfare, manufacturer’s profits and total social welfare. But they would also contribute to higher drug prices. “There is a complex interdependency between the subsidy budget, price and resulting welfare,” the authors conclude.

Featured Faculty

-

Christopher Tang

UCLA Distinguished Professor; Edward W. Carter Chair in Business Administration; Senior Associate Dean, Global Initiatives; Faculty Director, Center for Global Management

About the Research

Olsder, W., Martagan, T., & Tang, C. (2019). Improving access to rare disease treatments: Optimal subsidies, pricing and payment>