Researchers take on the difficult job of isolating for-profit prisons from a host of other factors

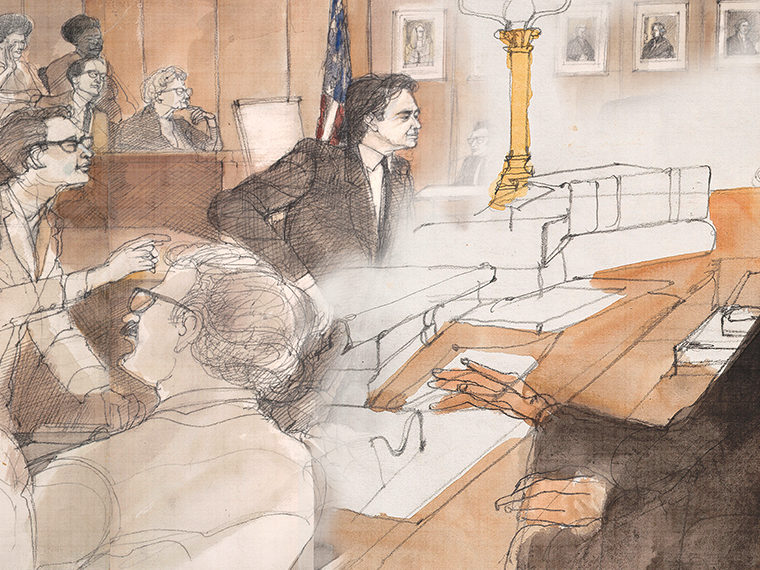

Do you recall the kids-for-cash scandal that broke a decade ago? Two crooked judges in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, accepted more than $2 million in bribes in a scheme to help get a private detention facility built, make sure a competing public facility wasn’t built, and funnel hundreds of minors into the jail, often for trivial offenses.

The case elevated the perverse incentives of for-profit prisons from the potential to the gruesomely real, and helped place private incarceration at the center of the growing movement in the U.S. to reduce overall imprisonment. The U.S. imprisons more people as a percentage of its population than any other country.

The Obama administration moved to phase out federal use of private prisons, a move since reversed by the Trump administration. Private detention facilities house more than 70 percent of immigrant detainees; of the overall inmate population in the U.S., private prisons house about 8 percent.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

There’s no doubt that private prison operators have spent money to influence sentencing policies and to elect officials who would help the industry. In 2016 and 2017, private prisons and the companies that serviced them spent $12.4 million on lobbying state lawmakers or state campaigns, according to the National Institute on Money in Politics, a nonprofit focused on campaign spending.

The question addressed in a working paper by UCLA Anderson’s Christian Dippel and Columbia’s Michael Poyker: Did the presence of for-profit prisons actually lead to a higher incarceration rate, when all the other factors involved are accounted for?

Those other factors would include: the opioid epidemic; three-strikes laws enacted in many states; the preferences of local police, prosecutors and judges to imprison people, including minorities in disproportionate numbers; and fluctuations in the actual incidences of crime, among other things.

Dippel and Poyker find a precisely estimated effect on longer sentences based on the opening of a private prison in a state, but this effect is small in magnitude: A doubling of private prison capacity in a state adds just 1.5 percent, or the equivalent of 23 days, to an average sentence. Contrary to concerns voiced by various think tanks, the researchers find no evidence that the presence of private prison operators increases the likelihood of being incarcerated, or that it disproportionately harms minorities or young people.

Dippel and Poyker created a database that geo-located public and private prisons in the United States dating back to 1980. Then they gathered extensive information on sentencing over the past three decades from Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, Nevada, North Carolina, Oregon, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia and Washington.

To establish the link between sentencing and private prisons, the researchers focused only on state-level circuit courts. They restricted their study further by looking at changes in sentencing decisions in felony cases within 236 circuit court pairs that straddled state borders.

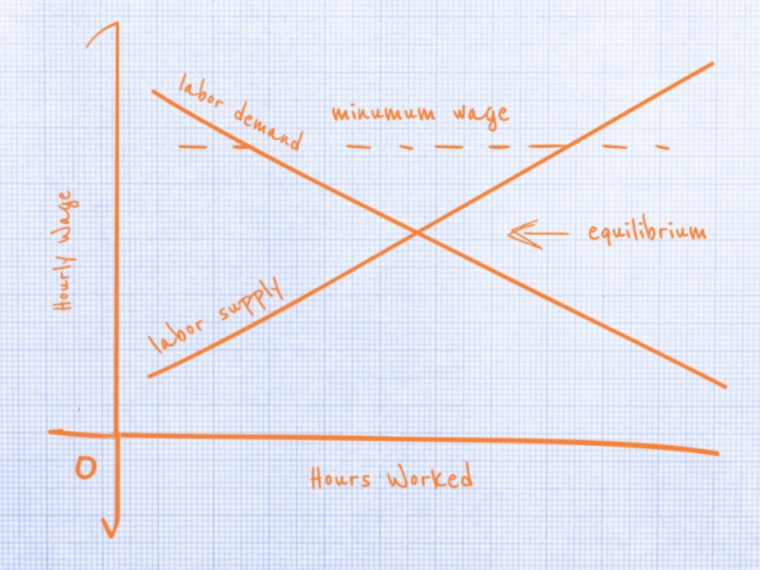

Researchers often use cross-border county pairs to identify the effect of state-level changes because it makes it easier to control for localized developments that might otherwise go unnoticed, such as trends in criminal activity. This type of analytical tool is also used in research on minimum wage and manufacturing policies. In essence, the theory behind this study design is that, by focusing on only neighboring counties around state borders, local conditions — particularly as they pertain to crime — can be held constant, so that cross-state differences in private prison capacity can be isolated.

With this database, Dippel and Poyker could track the impact of private prison capacity on sentencing length while controlling for prisoner characteristics such as age, gender and race. This allowed them to show that an expansion of private prison capacity led to a slight increase in sentencing lengths relative to the prisoner’s crime or background.

They also found evidence of racial bias in the prison system, something supported by previous research in this area. However, their findings did not suggest that an expansion of private prison capacity led to an overall increase in incarceration rates or harsher sentences for minorities or youth.

The authors try to pin down the mechanisms through which private prisons might influence sentencing. One possibility is private prisons put political pressure on judges. Such pressure is likely to be most effective in the lead-up to judges’ reelections. Many judges run for office every four years and there is a body of research showing that they tend to levy harsher sentences in the run-up to reelection. Dippel and Poyker hypothesized that this period would be the time when private prisons are likeliest to exert influence over sentencing. However, their analysis of sentencing data did not find evidence that the existence of private prisons changed the judges’ sentencing behavior tied to electoral cycles.

The authors also explicitly rule out law changes as the driver. While it might be that the expansion of private prison capacity in a state coincides or even causes harsher sentencing guidelines or laws, the authors designed their study so that such changes are statistically absorbed by flexible state-specific time shifters.

Instead, the authors conclude that the likeliest mechanism linking private prison capacity to sentencing length may be mundane fiscal considerations: There is considerable evidence showing that judges’ sentencing is partly influenced by the cost of incarceration and by incarceration capacity, probably because such fiscal considerations influence administrative guidelines that the governor or the states’ justice departments circulate. The notable thing about private prisons is that they almost always sign fixed-cost contracts in which the state government pays for the beds even when they are empty. Within the expanded capacity of a newly opened private prison, these fixed-cost contracts essentially reduce the fiscal burden of an additional prison inmate to zero.

The authors are in the process of obtaining very detailed California sentencing data to allow them to pursue this line of reasoning using a unique natural experiment caused by the Brown v. Plata, 563 U.S. 493 (2011) Supreme Court decision. This decision mandated California prisons to dramatically expand their capacity from 2011 to 2013 in order to reduce prison overcrowding. Preliminary data analysis suggests that the resulting capacity expansion considerably increased the average California circuit court sentence in that time.

Featured Faculty

-

Christian Dippel

Assistant Professor of Economics

About the Research

Dippel, C., & Poyker, M. (2018). Do private prisons affect court sentencing?