Establishment media coalesces around a lone narrative, but online chatter hops between storylines, sometimes shocking traders

The 2020-21 GameStop short squeeze helped teach Wall Street’s heavy hitters that even online nobodies can turn a market upside down. And since then, professional investors have realized there’s a lot of money to be made — and, just as importantly, losses to be avoided — by recognizing when ordinary online chatter is turning into a market moving revolution.

In a working paper, UCLA Anderson’s Thomas Ash offers a tool that might be used to spot such asset bubbles as they develop. His model of hypothetical asset bubbles captures how various theories of a company’s value gain and lose traction on social media. To demonstrate its predictive power for trading and share prices, he uses the model to replicate the growth and destruction of the GameStop bubble.

The Superpower of Social Media

Ash suggests that social media ramps up the size and speed of asset bubble formations, as well as their takedowns, by supercharging a narrative process as old as investing itself. Talkers in his hypothetical scenarios put forth theories of why a certain share price might be over- or undervalued. Listeners share their sentiments about these ideas through comments, likes and reposts that support or diminish the idea. The lightning speed at which this flood of online judgment can influence others makes today’s asset bubbles more extreme and unpredictable than those in the past fueled by traditional media, the study suggests.

Importantly, listeners in Ash’s model are open to changing their minds about selling, buying or holding shares. They want to make money, even if that means rejecting their own beliefs. Traditional narrative models used by finance and economics professionals often make listener beliefs fixed.

Bubble Signals, IRL

In July 2019, Bloomberg News reported that roughly 63% of GameStop’s shares had been sold short, a massive bet against the company’s prospects and stock price. The company, an old-school mall retailer, continued under heavy short seller pressure for another year. Then some mostly anonymous retail investors, convinced that the company was undervalued, started chatting online.

Initially, establishment investors seemed in denial about the potential power of what they regarded as dumb money. But by January 2021, those small-time investors had pushed the share price from its dollar-ish level to about $350. Some institutional investors paid dearly for failing to heed the amateurs. Hedge fund Melvin Capital, for example, died famously under its $6.8 billion loss.

Ash fed his hypothetical bubble model actual online narratives related to the GameStop bubble incident. He scraped the social media outlet Twitter, now known as X, for posts related to GameStop shares between April 2020 and April 2021. He identified various strong narratives as being optimistic or pessimistic about the share price.

The calibrated model then simulated GameStop’s share price changes and watched as the various narratives spread and stuck or foundered and faded. The model correctly predicted trading behavior during the period, including the general timing of the peak price and of the eventual crash.

The model fell short, Ash reports, on predicting the magnitude of the crashes.

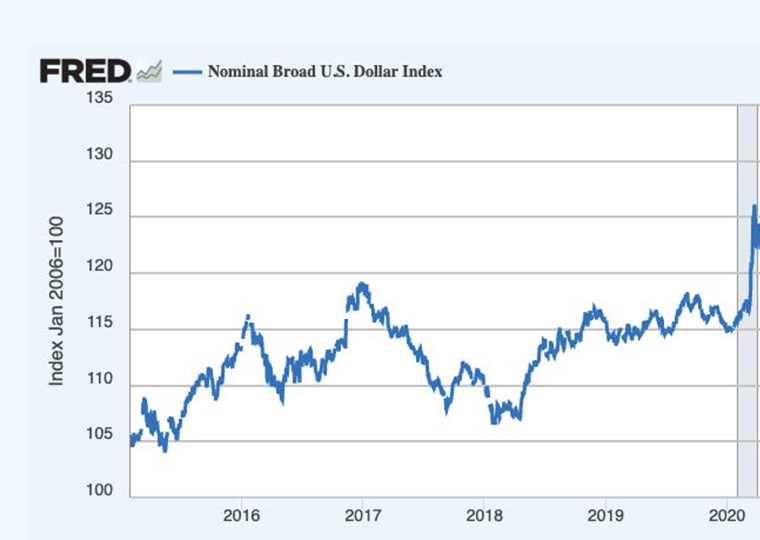

To recreate the Bitcoin bubble, Ash also included related narratives found in newspaper outlets between January 2017 and April 2018. He found that Tweets and other online discussion was stronger and more persistent than the responses to traditional news.

Calibrating the model with only the traditional news — assuming listeners were not on social media — Ash shows how bubbles formerly were slower to form and less dramatic in their sell-offs. He notes that traditional media tends to focus coverage around a single narrative, especially toward the peak of a bubble, whereas multiple narratives constantly compete online. In traditional media, novel narratives are slow to take off.

In the online discussions, Ash suggests that novel theories usually took over the conversation or died quickly, rather than lingering alongside others. These new ideas create exceptional volatility as listeners sort out whether they’ll reject the story or embrace it. Clusters of unique but similar narratives tended to reduce crash potential.

Most narratives have predictable impacts on share prices: Positive narratives lead to buying, while crash theories spark sell-offs. Ash’s model offers clues about which, if any, of those theories are winning the debate.

Featured Faculty

-

Thomas Ash

Economist, UCLA Anderson Forecast; Researcher

About the Research

Ash, T., (2024). Talking and Bubbles: Narratives in Social and News Media.