After the repo: Borrowers’ post-default payments account for 27% of lender recoveries

Two scenarios, both far from ideal:

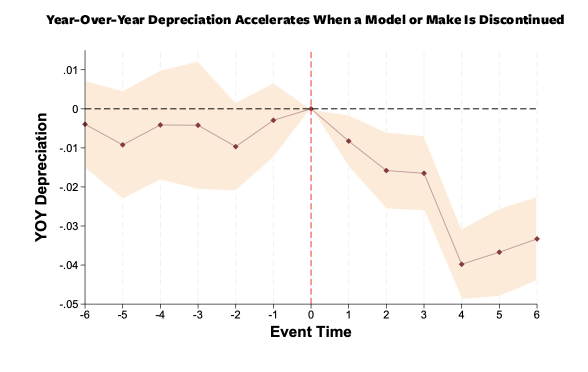

- You borrow to buy a used car and, a while later, the manufacturer discontinues the model (e.g., Buick Lucerne, Chrysler Concorde, Ford Freestyle). Or, worse still, discontinues the entire make (Oldsmobile, Pontiac, Mercury).

- The model or make was already discontinued and you bought one on credit anyway.

In both cases, as seen above, you’ve bought into a more rapidly depreciating asset than cars that haven’t been discontinued, a paper forthcoming in The Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, by UCLA Anderson’s Mark Garmaise, University of Utah’s Mark Jansen and BI Norwegian Business School’s Adam Winegar, documents. If you default on the loan, you’ll likely still owe a chunk of money after the car is repossessed, and it will be a bigger sum than if you’d bought a model or make that wasn’t discontinued.

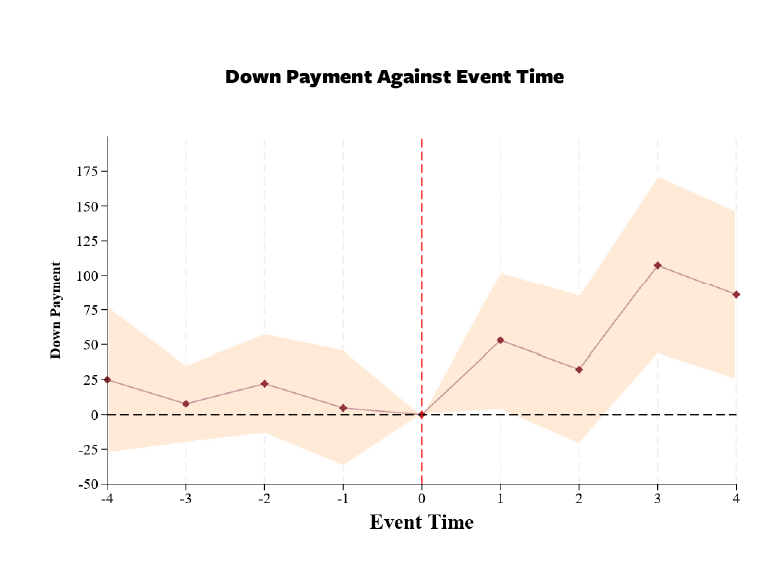

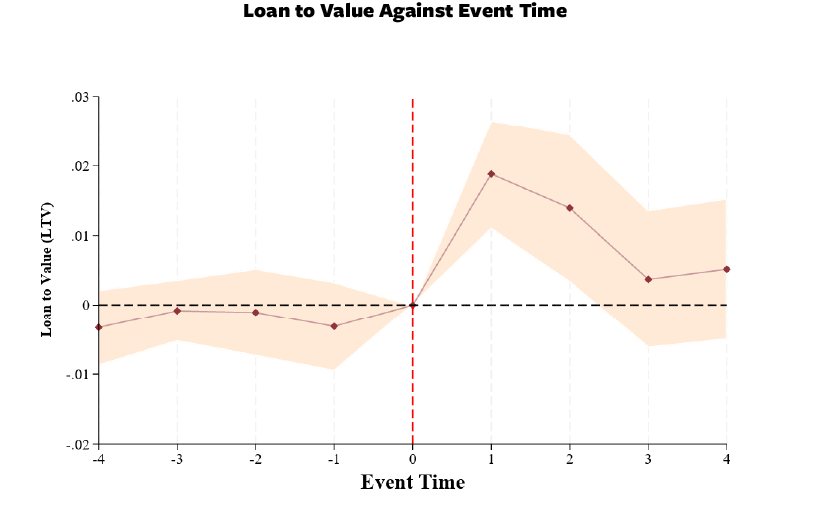

By comparing the same car model before and after discontinuation, the researchers were able to more clearly isolate how lenders (and borrowers) adjust loan terms when a car’s value declines. Older used cars are typically sold for a price well above their collateral value and to borrowers with a high likelihood of falling behind on payments. To improve the quality of the loan, lenders tinker with required down payments, loan-to-value ratios and borrower income coverage for the payments.

Within the researchers’ dataset, there were 208 discontinued models and eight makes, and the researchers verified that buyers of these discontinued cars tended to have lower incomes. And this lets the authors observe how default and lender recovery dynamics differ when the car itself has modest resale value.

Leveraging data on more than 300,000 used-car loans issued between 1992 and 2021 by a major subprime lender, in which nearly 77,000 fell into default, the researchers built a model that tracks the mechanics of how lenders are repaid after a repossession. They estimate that of the amount lenders manage to recover after default, an average of 75%, or $3,483, comes from resale of the car and about one-quarter, or $1,171, from payments made by the borrower after losing the car.

The dollar figures would likely be higher today given escalation of car prices. Cox Automotive reports that the $26,000 average list price for a used car in September 2025 was about 33% higher than it was before the pandemic, outpacing the 26% overall rate of inflation.

The researchers estimate that in the event a discontinued car is repossessed, about 27% of what the lender recoups comes from cash payments from borrowers, who are typically lower income.

That gap may seem small, but exposes a high cost for a lending model that can’t rely on collateral: When a car has too little resale value, lenders extract proportionally more cash directly from borrowers who can little afford it. It is just one of the ways subprime lenders have worked around the core problem that lower-wage individuals often can’t afford used cars that have enough resale value on which to base the loan collateral.

The researchers find that subprime lenders impose terms on the lower-income borrower to compensate for the lack of sufficient collateral. They document that borrowers of discontinued cars on average make higher down payments than other used car borrowers do. And yet, their loan-to-value ratios are higher. That is, they have to come to the loan table with more upfront cash than the average used car buyer, but because of those low resale values, still end up with initial loan balances that are a higher percentage of their car’s resale value than other borrowers.

The researchers show how lenders depend comparatively more on borrowers’ future income, not the cars’ resale value, when they make subprime loans.

At repossession, lenders extract relatively more in cash payments from lower-income borrowers who purchase discontinued cars than from others who finance used cars and go on to default. This supports the researchers’ thesis that the subprime auto loan market is skewed to the borrower’s income capacity, as opposed to the car’s collateral value. The authors note that this kind of income-based lending has become more practical over the past decade or so, as fintech tools have made it easier for lenders to verify income, automate payments and continue collecting payments even after a repossession.

Overall, it’s a precarious model for lenders, as the fall 2025 bankruptcy of two large subprime auto lenders suggests — especially when the economy is not in a recession. And if the deal seems particularly bad for lower-income people, there’s little alternative. The lack of robust public transportation outside of a handful of American cities effectively means many workers need a car to get to work.

Oldsmobile Alero

A 2024 report from the Bank of America Institute found that the percentage of people making less than $50,000 who had a car loan with a monthly payment of at least $500 increased from 30% in 2019 to 60% last year. The same report found a disproportionate burden falling on the financially vulnerable. The 34% increase in the median car payment for lower-income households between 2019 and August 2024 was nearly 10 percentage points more than the increase felt by the highest income borrowers.

The burden is becoming unmanageable for a growing number of lower income households.

Fitch Ratings reports that 6.5% of securitized subprime auto loans — lower-income borrowers typically have subprime credit profiles — were at least 60 days delinquent in September 2025, the highest level in more than 30 years. A forecasted 3 million repossessions this year — would be the highest since the Great Recession.

Featured Faculty

-

Mark J. Garmaise

Professor of Finance

About the Research

Garmaise, M., Jansen, M., & Winegar, A. (in press). Collateral Damage: Low Income Borrowers Depend on Income-Based Lending. The Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis.