Decision analysis for a firm considering adding a longer-aged product to its lineup

A 60-year-old bottle of Macallan Scotch whisky sold in November 2023 at auction for ₤2.2 million, or about $2.79 million. Even in the world of aged spirits, the price was an outlier, reflecting the bottle’s rarity — it was distilled in 1926 and bottled, which ends the aging process, in 1986 — more than connoisseurship. Still, 50-year-old whiskies can fetch as much as $60,000 a bottle, while a 25-year-old Macallan will run close to $3,000.

For distillers, however, waiting 25 or 50 years to make a sale represents decades of unrealized revenues and myriad risks. Older whiskies, like wine or Parmesan cheese, increase in value as they age, but they also require a bet on uncertain future demand. So, for a distiller that currently enjoys success selling a modestly aged whisky, the decision to add a longer-aged spirit is full of uncertainty.

A paper published in Decision Sciences, by Google’s Hossein Jahandideh, UCLA Anderson’s Kevin McCardle and Christopher Tang and University of Sydney’s Behnam Fahimnia, seeks to provide a template for this difficult decision.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

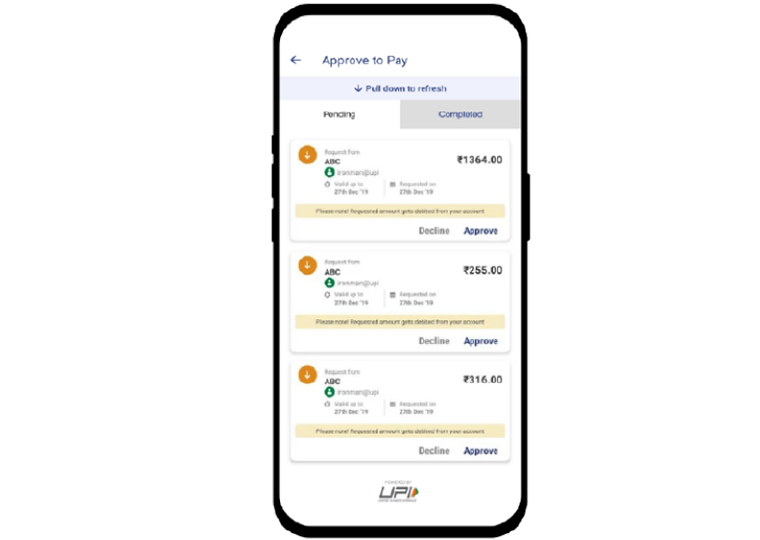

The distiller already knows the market size for its less-aged whisky, in the authors’ framework, having sold that product for years. Unknown is the size — units and price — of a longer-aged spirit the distiller might market. The distiller’s capacity, in this framework, is fixed, so the question is how much to allocate to various aged products. Given that aging (and thus, hoped-for rising value) stops at the point of bottling, there is no incentive for a distiller to hold onto bottled whisky; industry practice is to sell all bottled amounts immediately to distributors.

The Future Market for Very Old Booze

The authors’ model suggests that while it’s possible to devise an allocation strategy that produces the most revenue — a lot of math around price, units and time — such a complicated analysis isn’t necessary. Instead, an estimate of the size of the future market for, say, 25-year-old Scotch will enable the distiller to set a mix of younger and longer-aged whisky that is nearly as profitable as the optimal strategy.

Allocating production among a variety of products is common in all sorts of manufacturing. An automaker, for instance, needs to decide how many lines to devote to sedans and to light trucks. But the decision is complicated when it comes to long-aged items, like wine, cheese or whisky, where the maker has to defer some portion of current sales in the hopes that buyers in a distant future will be willing to pay enough to make up for various costs of waiting.

Making Scotch whisky is already a long-term project. Each year, a distiller malts and mashes germinated barley until it ferments, then the mash is distilled until it reaches an alcohol content of about 60%. The distilled spirits, known as “new make” (called moonshine in the U.S.), are matured in oak casks until alcohol content is reduced to about 40% to 45%. Scotch whisky by law has to be aged for a minimum of three years and fine Scotch typically matures for at least 10 years.

After the whisky reaches its desired maturation date, it is bottled and sold through distributors. (American whiskies are typically bottled much younger.)

The problem for the distillery seeking to maximize revenues from both products is to determine how much matured whisky to bottle for immediate sale and how much to set aside for additional aging. To find an optimal way to make this allocation decision, the authors’ model relies on three questions:

- Should the distiller sell all the available output or set aside some for continued aging? (If the longer-aged stuff isn’t much preferred to the lesser aged, what’s the point?)

- If there is to be a longer-aged product, what’s the right split between the two ages of whisky?

- Given the entire question here is about uncertainties, is it better to make the allocation decision all at once or gradually over time as the distiller gets more information about demand for the aged product? Releasing some of the older stuff into the market at the 25-year mark, say, and using the observed demand to better decide when to sell the remainder. (And, obviously, contemplating the sale of a $500 bottle 10 years out, say, one has to discount that price for inflation and other considerations. The question further assumes the distiller has the financial wherewithal to wait.)

A Bird in the Hand

In practice, distillers use market research and analytical tools to make allocation decisions, but these initial choices are often adjusted as conditions change. In the 1980s, a slump in demand for Scotch meant more barrels were left to age longer, leading to older whiskies coming available in early 2000s and fostering a view that age meant higher quality. Later, a surge in demand led many distillers to tap into their older casks and blend them with younger spirits, abandoning age statements on many 10- and 12-year-old whiskies.

Whisky makers also regularly check the quality of their aging spirits to make sure they haven’t lost too much alcohol to evaporation — known as the “angel’s share” — or haven’t picked up unappealing notes from the wood cask. A barrel set aside to age for 60 years might be tapped and bottled at 50 years — or 35.

In the end, not many bottles go the distance. In 2020, only 274 bottles of Highland Park 50-year-old were available, selling for $15,000 each, while only 50 bottles of Dalmore 50-Year-Old were being sold, priced at $60,000 each.

Featured Faculty

-

Kevin McCardle

Professor Emeritus of Decisions, Operations and Technology Management

-

Christopher Tang

UCLA Distinguished Professor; Edward W. Carter Chair in Business Administration; Senior Associate Dean, Global Initiatives; Faculty Director, Center for Global Management

About the Research

Jahandideh, H., McCardle, K., Tang, C., & Fahimnia, B. (2023). Capacity Allocation for Producing Age-Based Products. Decision Sciences, 54(5), 473–493.