Companies that take longer than expected to announce results may be buying time for accounting tricks

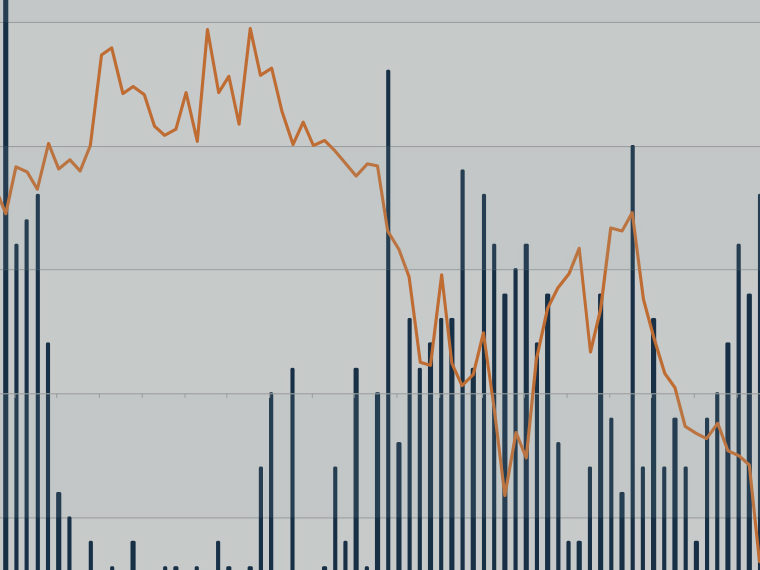

When corporate-earnings reporting season ramps up four times each year, companies can be expected to hold to historical patterns: If they’ve got good profit news to share with investors, they have an incentive to report results earlier than usual; if the news is bad, however, they may take longer to fess up.

Yet some research has shown that nearly 30% of companies that unexpectedly chose to delay quarterly earnings statements ended up reporting positive earnings surprises, not negative ones.

UCLA Anderson’s Mark P. Kim, Florida State University’s Spencer R. Pierce and University of British Columbia’s Ira Yeung wondered what motivation those firms would have for putting off their results, particularly given investors’ natural suspicion of late-arriving reports. The researchers dug deeper and the result is a working paper that suggests that a company’s decision to hold back results often is an attempt to buy time for financial alchemy — that is, to use certain accounting techniques to boost reported profits.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

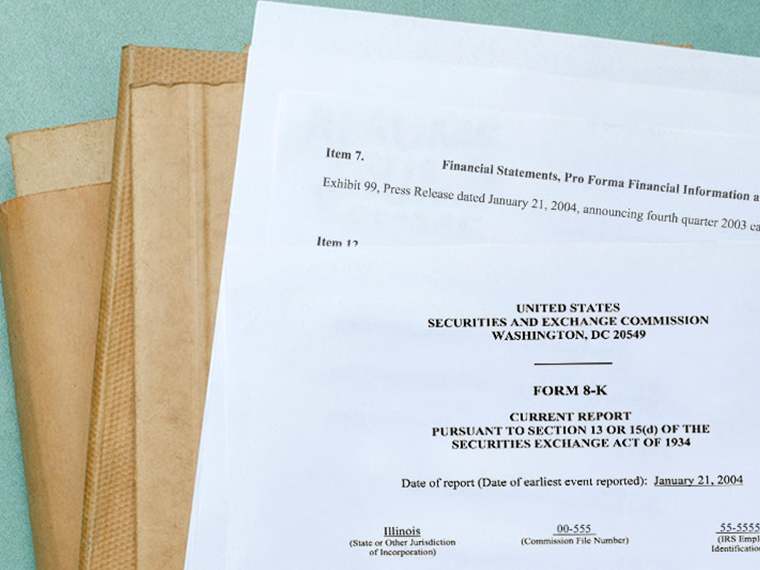

The authors collected data on U.S. companies between 1989 and 2016. They excluded firms in heavily regulated industries and in financial industries because of accounting practices that differentiate those sectors from most others. That left 4,460 companies as the basis for the paper, of which between 10% and 15% were found to have unexpectedly delayed annual earnings announcements in any given year.

The study focused on companies’ fourth-quarter reports, with the idea that corporate managers might be most interested in bolstering full-year results. Federal rules require companies to report annual financial data within 60 days of year-end. Typically, companies favor the same reporting dates each quarter; some issue results quickly, while others take longer. For their paper, the researchers considered a report to be unexpectedly “late” if it was issued more than three trading days after the company’s usual announcement date.

The paper distinguishes between real earnings management and manipulation of accruals to accomplish earnings management. Real earnings management would include activities like moving inventory such as computers off a company’s loading dock before they’re actually scheduled to be shipped to a customer and before period’s end to be able to book the items as sold and thus include the revenue. By definition, real earnings management has to occur before the end of the reporting period for it to be counted.

Accruals, such as a provision for environmental reserves, can be determined after the end of a period and thus allow for manipulation after the fact.

The authors first looked for evidence to determine whether late reporters were using any of three classic “real earnings-management” strategies described in a 2006 paper by Sugata Roychowdhury: abnormal discretionary expenses, abnormal cash flow from operations or abnormal production costs. But Kim, Pierce and Yeung write that they found “no relation” between the use of those techniques and delayed reporting of quarterly results.

It was a different story with two other ways to alter reported profits. One is via the management of accruals. On a company’s income statement, an accrual item may be as simple as recording revenue from products sold but for which payment hasn’t yet been received. Accruals also can be more complicated; for example, a company could boost reported earnings in a given quarter by choosing to reduce estimates of product warranty costs.

Using statistical regression, the study found that “late announcers of good news exhibit significantly more income-increasing discretionary accruals relative to firms that report good news early and firms that report bad news late.”

The authors also found “strong evidence” that companies looking for a late fix to boost reported earnings often seek to reduce quarterly tax expenses. The study notes that the mechanics of accounting make 11th-hour changes to tax rates a prime strategy for companies desperate to boost profits: Tax expense “is one of the last accounts to be closed and audited before firms announce their earnings, making it an ideal account to identify last-minute earnings manipulation,” the study says.

Of course, “manipulation” is a loaded word, raising a troubling question: Do any of these accounting tricks break the law, or at least bend it, in the effort to beat Wall Street earnings targets? In an interview, Kim said, “The term ’earnings management’ in accounting literature is more often narrowly defined as management tactics deemed ’in conformance with U.S. GAAP’” (generally accepted accounting principles). Even so, he said, “It is possible that some of these tactics may not be quite exactly legal,” but the paper makes no judgments.

Another logical question is whether investors are fooled by such profit manipulation. By one measure — the performance of the stocks — companies that delay results, then beat profit expectations when they report, don’t exactly get a rousing market reception: The study found that shares of late reporters of good earnings news linked to tax-expense management lost 1% on average over the two-day window that included the announcement date, when compared with late reporters of good news unrelated to tax-expense management.

A 1% decline may not seem like much, but keep in mind that a company’s goal in beating profit estimates is to boost its stock, not drive it lower. A falling stock price after better-than-expected profit may signal that the market is suspicious about the “quality” of the earnings — for instance, how much of the growth can be attributed to the basic business.

In the interview, Kim said companies may have incentives beyond topping short-term earnings targets to bolster reported results via accounting techniques. For example, a company’s lending limits with its banks may depend on maintaining a certain level of profitability.

At the very least, Kim suggests, investors should consider that “good news released at an unexpected delay is an earnings quality red flag.”

Featured Faculty

-

Mark Kim

Assistant Professor of Accounting

About the Research

Kim, M.P., Pierce, S.R., & Yeung, I. (2019). Eleventh-hour earnings management and financial reporting timeliness.