Can modern decision theory, paired with a half-century-old thought experiment, help make a more just society?

Fifty-two years ago, the American philosopher John Rawls authored what would become an enormously influential book, “A Theory of Justice.” In it he put forward a now famous thought experiment: Imagine the principles of justice in a society but assume you don’t know your place in it — poor, rich, educated, ignorant, safe, vulnerable. Considered with any seriousness, the experiment has a way of separating people from some of their biases.

That same year, 1971, UCLA Anderson’s Rakesh Sarin finished his MBA in India and launched into Ph.D. studies in the U.S. around individuals’ decision making in business and in life. Sarin authored many papers on narrow topics of choice, access to information and other factors that affect decisions. It’s a highly practical field that often helps companies trim costs, boost output or better understand the behavior of customers.

As time went on, Sarin was also considering how and why we choose to structure societies the way we do. And, beginning in the mid-1990s, he would apply his theories on decision making to considerations of fairness, then happiness and, mostly recently, what constitutes a just society.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

The U.S. — and indeed, the world — hardly lacks for spirited debate on the shape of civilization these days. But so much of it is either partisan belligerence or self-interested pro and con on a specific issue, with notions of justice and fairness enlisted to prove one’s point. It sounds chaotic, and it is.

Sarin believes the process of imagining a just society — individually and collectively — might make public discourse more constructive and less combative, helping to identify shared values and goals.

Three Models to Choose From

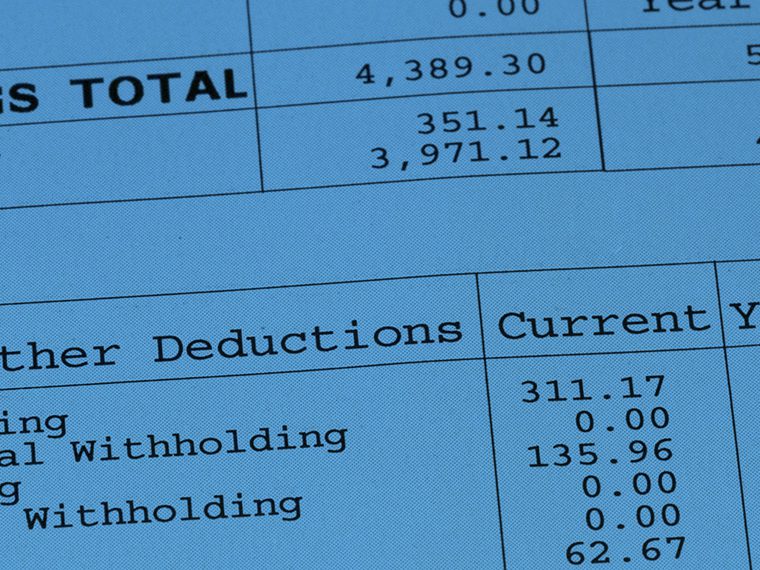

In a paper published in the journal Theory and Decision, Sarin pairs the Rawls thought experiment with three economic models. You could be a teenager or a patriarch in a wealthy family. Perhaps you’ve worked ceaselessly for decades to build a very successful company and now enjoy every perk money can buy. Or maybe you’re a veteran, homeless and struggling with mental health issues. A laid-off cancer patient. Or an underfed, occasionally housed, sporadically schooled child with drug addicted parents. You don’t know, and you’re tasked with choosing the best wealth-redistribution scheme for your society.

Sarin runs this hypothetical scenario through a decision model, similar to those popular in corporate America, to reveal the optimal outline for a just society — the one, from among these three, that a rational, self-interested individual would choose in this experiment:

- Laissez-faire. Characterized by minimal market regulations and limited social supports for those who do not earn sufficient wealth in the market. Generally, individuals keep what they accrue in the market. Of the three systems, this one generates the largest amount of overall wealth in the nation.

- Social minimum: Wealth is redistributed to give the least advantaged a decent standard of living. Deep disparities in wealth are acceptable as long as basic needs, such as health care, housing and food, are amply covered for everyone. Sarin describes social minimum as “not just enough to live a life,” but enough to ensure you “live a life of dignity and self-respect.”

- Social maximum: Continual redistributions with the goal of maximizing the welfare of the worst off. Based on Rawls’ philosophy, which argues that every benefit to the most advantaged in society should be shared with the least advantaged, this system creates the most wealth equality and the least overall wealth.

Redistributions, most commonly through taxes on income to subsidize programs for the less wealthy, always reduce overall wealth through administrative and other transfer costs, Sarin explains.

The U.S. economy sits somewhere between laissez-faire and social minimum, notably failing to deliver adequate health care, housing and nutrition for all, while some developed economies in Europe and elsewhere come closer to achieving social minimum.

“‘Just societies,’ in most people’s minds, is a purely philosophical topic. Not in my mind,” Sarin says. But, he says, “you have to engage in hypotheticals to get clarity” about what’s really fair.

How Do You Model Fair?

Decision theory is based on the idea that the outcomes an individual wants — what makes them happy — are implied by the choices they make. Given that information, a decision model predicts the end result when the subject takes the most rational options over a series of choices, about almost anything.

Large businesses are particular fans of decision modeling. A couple of examples of why: A pharmaceutical company could use a version of decision theory to predict the changes to competition and profits if, for example, it moves all the melanoma research money over to the arthritis drug budget. Managers elsewhere might use decision analysis to forecast how much money they could lose if their worst fears about a takeover target are realized.

Sarin’s early research focused on analyzing decisions of individuals to improve decision modeling. In this work, he says, “fairness” was not part of the equation. The optimal decision is the one that gives the decider the most “utility,” or satisfaction. (Wealth is a component of utility.) For a successful entrepreneur trying to choose a societal home, the best choice is the one where he gives up the least wealth and is least restricted in collecting more, even if the majority of the population is perpetually poor.

But as the disadvantaged in that rich guy’s nirvana knows, the best decision for an individual isn’t necessarily the best for a group. For example, tax cuts that are good for the wealthy will be detrimental to the majority because less is collected for services to help them.

Sarin and his colleagues wanted to build decision models that incorporated fairness as a goal. “It cannot really just maximize my company profits or my own well-being,” he says. “It ought to include others.” He describes an ethical perspective for decision making as “self-interested, not selfish.” There’s some component of altruism.

In multiple research papers, Sarin and his colleagues illustrated just how tricky it is to define the elements of fairness. People have strong opinions about what’s fair, he says. They are not always rational.

Studies included examples of outcomes that are inherently fair to individuals but unfair to some subgroups. A new airport makes travel easier for everyone nearby but also creates incessant noise only for the subgroup that lives on its edges. A war draft that randomly chooses conscripts but groups them for battle by hometown is fair on an individual level but devastating to a small town if an attack kills its entire troop.

Fairness, Sarin concluded, always comes down to how something is distributed, whether benefits or risks. He and his colleagues made these distinctions more precise in the models.

The Most Just Choice

When Sarin employs the “veil of ignorance” — imagining a society without knowing one’s place in it — in a decision model, he concludes that the social minimum principles are fairest to everyone.

A laissez-faire system, economist Adam Smith famously describes, allows decisions of self-interested individuals to improve overall societal welfare by incentivizing effort that generates the most copious wealth. But Sarin finds the stakes too high for someone of unknown status to rationally choose this system. No one wants to risk ending up in abject poverty with little or no life support.

Rawls determined that a group of people making this choice would settle on the social maximum system. That’s a contract theory perspective, which predicts results after debate and concessions of multiple individuals.

Sarin, however, is interested in the best choice for a self-interested individual. The maximum system, he says, does not leave enough wealth to make it the best choice. The continual disbursements limit incentives for creating wealth — much can be taken away after earning it — and the transfers shrink overall wealth too much.

Although Rawls argues that the size of the pie is irrelevant here, Sarin says it is a key component. “My approach is frankly more common sense,” he says. “That if you really took this experiment seriously, you would really want some trade-off between the size of the pie and (how much) the lowest piece is.”

“In order to maximize your own expected utility — I’ll use the word happiness — I would make sure that this social minimum is decent. Not just barely enough to live a life,” he says. “You don’t want to get in a situation where you cannot carry out your life’s plan because you don’t have that education or health coverage.”

Sarin is not surprised if your choice of a just society in this experiment isn’t what you espoused in your real life yesterday. He says the exercise, a bit of fantasy alongside quadratic equations, eliminates personal biases that prevent rational assessment of what’s fair for all.

“If you assume that you want to live in a society… where you do not know your position — you can be rich or poor or healthy or not; even your gender is unknown — aren’t you going to look at it differently?”

Featured Faculty

-

Rakesh Sarin

Professor of Decisions, Operations, and Technology Management; Paine Chair in Management

About the Research

Sarin, R.K. (2021) Just Society. Theory and Decision, 91:417–444.

Baucells, M. and Sarin, R.K., “Optimizing Happiness,” 249-273 in A Long View of Research and Practice in Operations Research and Management Science, Sodhi, M.S. and Tang, C.S. (Ed.), Springer, 201.

Keller, R.L. and Sarin, R.K. (1995) “Fair Processes for Societal Decisions Involving Distributional Inequalities” Risk Analysis, Vol. 15, No. 1.

Fishburn, P.C. and Sarin, R.K. (1997) Fairness and Social Risk II: Aggregated Analyses. Management Science, Vol. 3, No. 1.