Improving the search for contractors that don’t use coercion

U.S. agriculture has a forced-labor problem. Actual numbers are hard to come by, but a recent analysis by a group of researchers suggests that the risk of forced labor is “pervasive” in the food supply chain.

Globally, nearly 28 million people in 2021 were working under coercion, the International Labor Organization reports. In this modern form of slavery, employers withhold pay or work documents, keep workers in debt bondage — making loans to be repaid from wages but in fact never are — and use physical threats to make workers toil against their will.

Even socially responsible companies can indirectly employ forced labor. Particularly in agriculture and food processing, farmers, ranchers and processors frequently rely on third-party recruitment agencies to hire and manage their workers. The agencies, which agree to provide a certain number of workers at a set wage, can turn to forced labor if they can’t recruit enough workers at the offered pay.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

Companies face significant legal and reputational risks if forced labor is discovered in their supply chains. They can reduce that risk with audits to ensure that agents are complying with labor laws, but such audits can be expensive. A working paper suggests companies can keep forced labor from their supply chains, at a lower auditing cost, with contracts designed to identify labor contractors that are less likely to use coercion.

“Buyers are exposed to the risk of involving forced labor when they rely on agencies to recruit,” write the authors — ESSEC Business School’s Felix Papier, UCLA Anderson’s Christopher Tang and ESSEC’s Javaiz Mohamed Parappathodi. “As such, there is a need to develop mechanisms to deter these agencies from coercing workers into forced labor.”

The use of labor contractors is widespread in U.S. agriculture and food processing. Because the work is typically seasonal, agribusiness companies need to bring in large numbers of temporary workers at planting and harvest times, and it’s easier and less costly to go to contractors to recruit, hire, train and manage the workers in the field.

Recruitment agencies also frequently handle the paperwork needed to bring in farmworkers from Mexico and other countries; recruitment agencies filed 44% of the requests for temporary work visas, known as H-2A, that were issued in 2023, the paper says.

When labor contractors are used, companies have little control or oversight over hiring and at the job site, creating opportunities for unscrupulous agents to use various forms of coercion to get laborers to work for illegally low wages. In one such case, federal prosecutors in 2021 charged 24 labor contractors with forced labor and other crimes for exploiting H-2A workers from Mexico, Guatemala and Honduras. The workers were illegally forced to pay for transportation, food and shelter and had to turn over their travel and identification documents, the indictment charged.

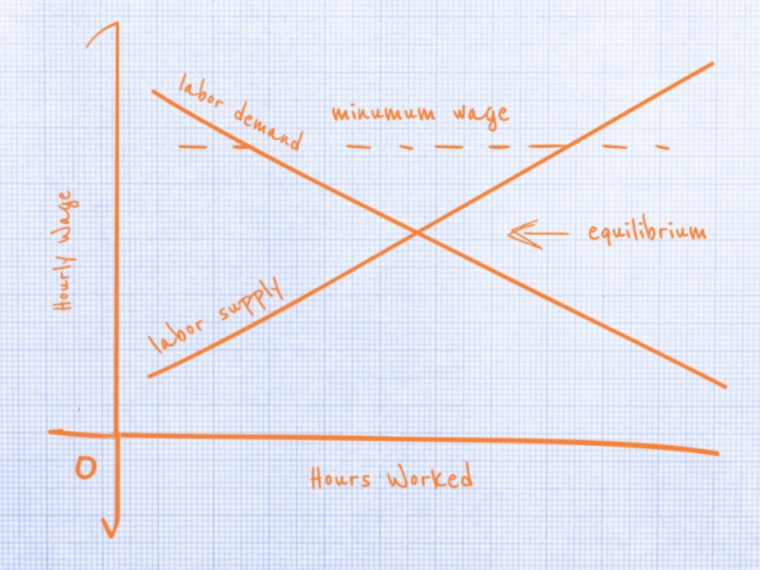

To explain the economic and contract conditions that contribute to the use of forced labor, the authors use a game-theory model that analyzes the interaction between workers, labor agents and the company that contracts with the agent. In the model, agents will use forced labor when they don’t have access to enough workers willing to work for the rate the buyer offers; instead of paying more (and reducing their fee), they will turn to various forms of coercion to get crews to work for less.

In the analysis, then, a company can avoid forced-labor risks by hiring an agent with a large pool of workers. The difficulty is getting the agent to truthfully reveal the size of its labor pool.

As a solution, the paper proposes offering prospective agents a “menu” of contracts featuring a range of contract options:

- At one end, the buyer would offer to hire fewer workers at a higher per-worker rate (making up the number it needs internally or with other agents). Because fewer workers are hired, a lower level of auditing is required.

- At the other, the buyer would offer to hire more workers, but at a lower rate, which would offset the cost of more thorough auditing and making the intention to thoroughly audit known to the labor supplier.

An agent with access to a small number of workers would choose the first to earn the most profits, while one with a large labor pool would choose the second to maximize revenues. In either case, the contract is canceled and the agent isn’t paid if an audit turns up signs of forced labor.

The buyer doesn’t present the full menu of contracts at once. Instead, it offers the options in multiple rounds, similar to a Dutch reverse auction. In such a process, common in procurement, the buyer steadily increases the offered price until a supplier accepts the bid.

Here the buyer starts by offering a contract for a large number of workers and then reduces the size (and raises the per-worker wage), until an agent accepts. If more than one agent accepts, the buyer selects the winner at random. In this way, the company can maximize its profit while reducing the risk of forced labor in its supply chain.

Featured Faculty

- Felix Papier

-

Christopher Tang

UCLA Distinguished Professor; Edward W. Carter Chair in Business Administration; Senior Associate Dean, Global Initiatives; Faculty Director, Center for Global Management

About the Research

Papier, F., Tang, C. S., & Parappathodi, J.(2023). Forced Labor in Labor Supply Chains — Contracting and Information Asymmetry, ESSEC Business School Research Paper No. 2023-03, Available at SSRN 4523642.