Chris Tang’s research suggests a two-step pricing strategy can maximize sales and profits

Consumers have grown accustomed to a steady stream of novel goods and services — smart televisions, contactless payments, ride-sharing from Uber and Lyft. Still, such innovations often can be a hard sell. They require buyers to give up old habits and to master new ways of doing things. Even when an innovation offers obvious benefit, getting people to try it means overcoming deep-seated psychological resistance to novelty and change.

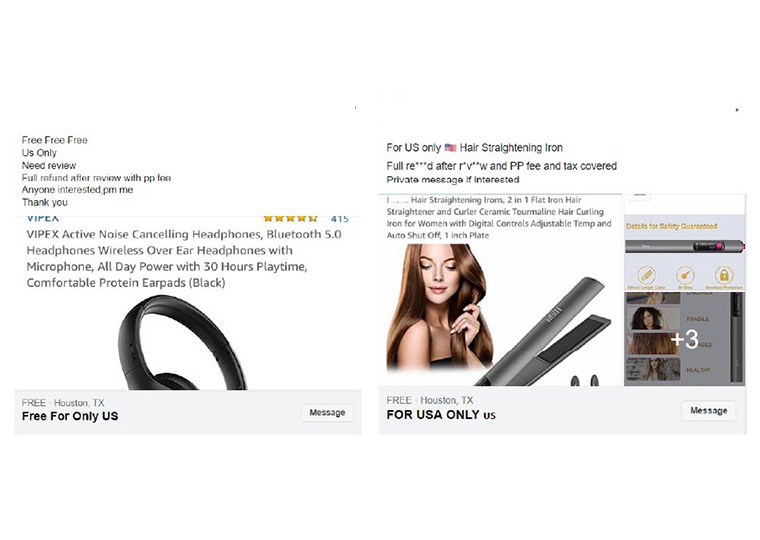

How can a company break through? One way is to help consumers become more familiar with a new product through advertising, promotions such as free trials, or showrooms where customers can gain hands-on experience with unfamiliar products (think: Apple Stores).

A paper from UCLA Anderson’s Christopher Tang, University of Bath’s Yufei Huang, and Bilaovl Gokpinar and Onesun Steve Yoo of University College London suggests that may not be the best approach, at least not for a company’s long-term profits. Instead, they say, it can be more lucrative to use initially low prices to woo early adopters, whose presence can reduce the anxiety felt by holdouts. When late adopters rush into the market, the company can profitably mark up prices.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

They also suggest there’s a flip side to the problem of consumer anxiety in the face of novel products. Resistance to innovation “benefits the innovative firm because it allows the firm to reap reward from the premium price charged to a group of late adopters,” the authors write.

In the paper, published in February in Production and Operations Management Journal, the authors devised an economic model to investigate the interaction between promotional and pricing strategies and the presence of early adopters in overcoming consumer resistance to innovative products. (The authors refer to consumer anxiety about innovation and the presence of early adopters as “externalities,” outside factors that either suppress or increase demand for the novel product.)

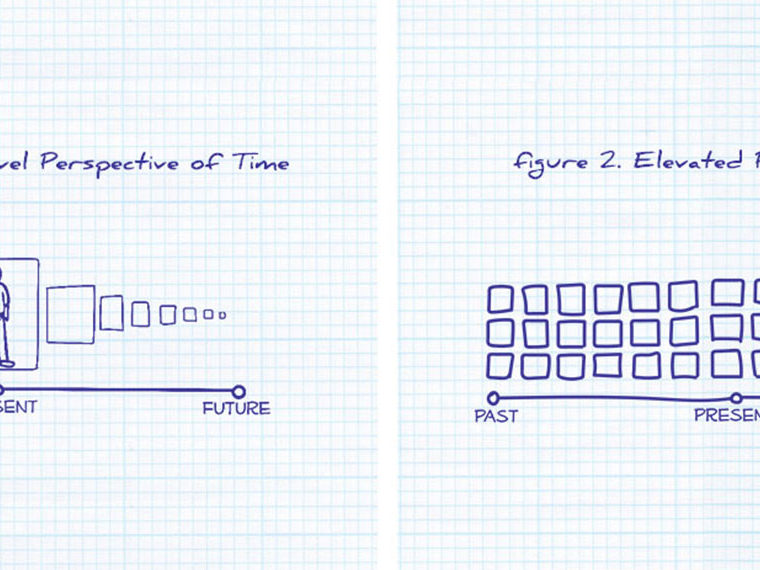

The model assumes that when faced with a novel product or service, consumers are going to respond with different levels of resistance. Some will have little anxiety about the purchase and will be quick to try it out, while others will delay their purchase. Often the procrastinators will wait to learn more about the value of the product from the experience of the early adopters. But in the authors’ model, the number of early adopters is key: the more there are, the more comfortable holdouts will feel about taking the plunge.

The model suggests that introducing the product with a low price is the best way to bring in the optimal number of early adopters. This will draw low-resistance buyers but not a rush of high-resistance customers. When that group gets sufficiently comfortable to start buying, the company can raise prices, boosting overall profits.

Promotional activities can also be effective at easing customer anxiety. But according to the model, they can work too well, bringing in so many customers during the promotional period that there are too few late adopters left from whom to collect premium prices. “There is economic incentive for the firm to decelerate adoption through its optimal pricing and promotion strategy,” the authors write.

So how does Apple succeed with a familiarization strategy featuring eye-catching advertising and hands-on showrooms? Tang suggests in an interview that Apple has over the years created a brand and built up a fan base comfortable with the company’s string of innovations — the iPhone, the iPad, Apple Watch. “If Apple did not have a brand, then it would be a challenge for them to get traction,” he says.

Featured Faculty

-

Christopher Tang

UCLA Distinguished Professor; Edward W. Carter Chair in Business Administration; Senior Associate Dean, Global Initiatives; Faculty Director, Center for Global Management

About the Research

Huang, Y., Gokpinar, B., Tang, C.S., & Yoo, O.S. (2018). Selling innovative products in the presence of externalities. Production and Operations Management Journal, 27(7), 1236–1250. doi: 10.1111/poms.12864