Research across cultures seeks to understand how status is achieved and maintained

It’s hard to imagine a work team, an organization or society as a whole without an internal hierarchy. Status represents each person’s relative standing in the group. Some members are considered more important, some less.

This ranking is far from trivial. Those with high status get more attention, their ideas are more respected and they are likelier to impose their views on the group. At least one study suggests that high status individuals live longer.

Social science researchers have long tried to understand status and how it works. Do groups automatically sort themselves, or do individuals work actively to boost their relative position? Do status hierarchies benefit or harm group performance?

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

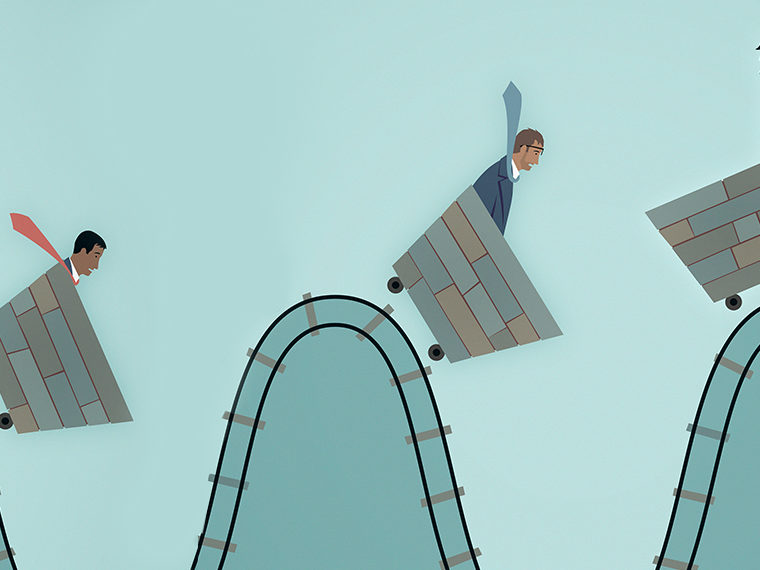

Recently, scholars have come to see that the process of assigning and maintaining status isn’t static but is constantly in flux. Members jockey for higher position or maneuver to defend their standing. Teams often use dubious criteria, such as gender or race or the overconfidence of ambitious leaders, to confer status. Groups reassess rankings in the light of actual performance.

In a paper published in the Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, UCLA Anderson’s Corinne Bendersky and Jieun Pai summarize the large body of research into this novel view of status and map out questions for future studies. The goal, they write, is to gain a better understanding of “how people gain or lose status over time.”

The paper considers such questions as: How do group members react when others try to gain or defend their standing? Are some status-seeking tactics more or less effective? Do people seek status differently in other cultures?

Bendersky and Pai define status as “the social value that observers ascribe to an individual or group.” It is different from power, which implies a degree of control over people or resources. One way to think about the difference: Hollywood actors have high status, but little power, while the people at the DMV have power but little status.

Traditional research considered two main ways that status is acquired. In one, groups rank members based on their perceived competence or expected performance. Others looked at how individuals actively seek status, either by dominating the group or by sending signals about their potential value — that is, by projecting self-confidence or touting their credentials.

What some recent research has found is that however it is gained, status is far from stable. Not only do group members try to improve or defend their positions, but the team as a whole often has to reconsider the hierarchy because the initial ranking wasn’t based on the actual ability of members. One study, by Bendersky and Rutgers’ Neha Parikh Shah, showed how extraverts — who gain status by projecting self-confidence — can lose their position when their actual contributions don’t match expectations.

A dynamic view of status opens new avenues to better understand the challenges women face in gaining high positions in organizations. Gender, like race, is what social scientists call a “diffuse” characteristic that provides little or no guidance about how an individual will actually perform. (Contrast that with specific traits like experience or educational attainment.) In societies that confer higher status to men than women, teams may automatically place males at the top of the hierarchy and rank women lower, regardless of their actual abilities.

One question for future research: Are women’s status-seeking efforts viewed more harshly than men’s and, if so, how can they avoid a likely backlash? One possibility, the authors suggest, is that women can rise in status not by actively competing for it, but through cooperation and generosity, which fit with existing gender stereotypes.

Researchers have seen that high status can be gained both through self-promotion and unselfish dedication to the group. Further study can indicate whether the most effective approach depends on the makeup of the team or on the nature of the assignment. For instance, cooperation might be rewarded when success depends on everyone’s working together. Being assertive may win higher status in groups with short-term assignments, since information about actual competence may be slower to emerge.

More research could also examine how status dynamics play out in different cultures. A 2014 study suggests that individualistic cultures such as in the U.S. tend to confer higher status on competence, while Latin American cultures, which the authors say are more “community-oriented,” give higher status to those who show warmth. In East Asian cultures, according to a 2016 study, high-status individuals maintained their positions through the use of punishments and other dominance tactics. “These studies suggest that additional research on status dynamics across national cultures could be informative,” Bendersky and Pai write.

Featured Faculty

-

Corinne Bendersky

Professor of Management and Organizations

-

Neha Parikh Shah

Human Resources & Organizational Behavior, Ph.D. candidate

About the Research

Bendersky, C., & Pai, J. (2018). Status dynamics. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 183–199. doi: 10.1146

Bendersky, C., & Shah, N.P. (2012). The downfall of extraverts and rise of neurotics: The dynamic process of status allocation in task groups. Academy of Management Journal, 56(2). doi: 10.5465/amj.2011.0316