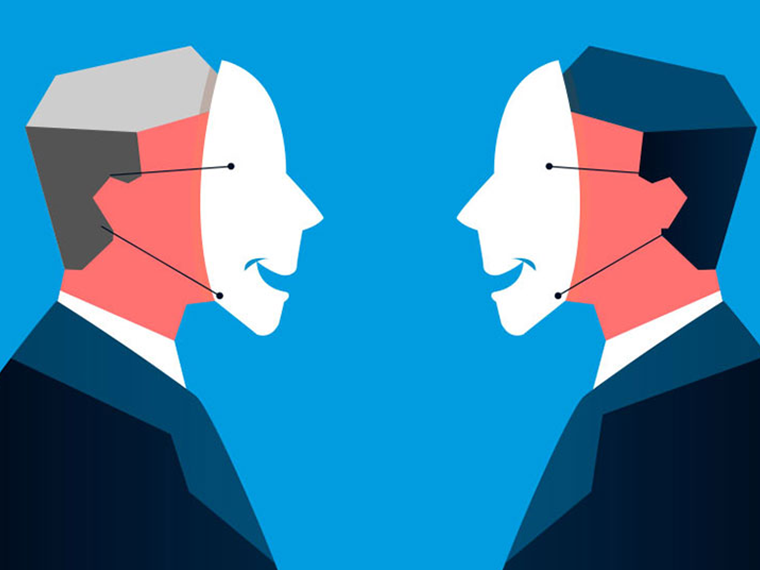

Analysis of 250 studies finds the most common response to negative workplace behavior is an eye for an eye

Nearly one in five U.S. workers has been exposed to on-the-job harassment or other forms of social antagonism. Younger workers, being a few rungs down the organization ladder, seem even likelier targets. Nearly one in four workers surveyed who are younger than 35 has reported being on the receiving end of workplace nastiness.

Much of the academic attention around workplace hostilities has focused on the nature of negative behaviors, how employees perceive those negative behaviors and their perception of management’s awareness and response to harassers and bullies.

Less studied is how bad behavior by one employee triggers a retaliatory response — as well as the ferocity of the response. Suffering in silence has long been one coping mechanism.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

But many workers fight back against negative behavior, countering with their own inappropriate acts. In relational research, two theories have emerged. One camp says that when we’re on the receiving end of a colleague’s hostility, we lash back (or, goodness, we lash out at others) at a commensurate level. Other studies reveal escalation: a target that strikes back more fiercely.

Oklahoma State University’s Lindsey Greco, UCLA Anderson’s Jennifer A. Whitson, Indiana University’s Ernest H. O’Boyle, Northwestern’s Cynthia Wang and Penn State’s Joongseo Kim set out to see if a more definitive answer on the mechanics and repercussions of workplace retaliation could be teased out of a trove of existing research.

In a meta-analysis that looked at nearly 250 previous studies (some of which were also meta studies) that incorporate the feedback of almost 100,000 participants, the researchers found that a commensurate, or eye-for-eye, retaliation toward the transgressor is the most common degree of payback. But retaliation that packs more intensity (escalation) was shown in the data to be a close second. A distant third: a response that aims to de-escalate.

For managers who take the stance that they won’t step in on the first transgression, or don’t telegraph their interest in knowing of any transgression: bad non-move. The data set suggests that just one “negative workplace behavior” (NWB) by an employee can trigger the worker on the receiving end to lash out with his or her own negative behavior.

“A primary practical implication of the work is that managers who stop one NWB from Party A are, in fact, likely stopping multiple negative behaviors from a multitude of Party Bs,” the authors write in a paper published in the Journal of Applied Psychology. “Limiting one NWB severs the chain of negative reactions and has important implications for the overall level of NWB in organizations.”

The researchers first combed through relevant research and tallied all the negative workplace behaviors that had been studied, such as harassment, bullying, incivility, aggression and ostracism.

At its heart, the study set out to categorize specific negative behaviors and negative retaliation, not on the kind of action, but on the severity of the behavior (minor, moderate, severe) and whether the action was passive or active.

To create those measures of severity and active versus passive behavior, 348 volunteers recruited on Amazon’s MTurk waded through the data and rated negative behaviors on a scale of 1 (not very) to 7 (very). Based on that analysis, the researchers were then able to sort the behaviors along the spectrum of low, moderate or severe. Other studies, for instance, have rated general incivility as an example of minor severity, while bullying might rise to the moderate level and aggression and physical violence would be examples of severe retaliation.

From there, the researchers were able to dive into studying the possible correlation between Party A’s behavior and the response from a Party B. Keep in mind, this is a meta-analysis of individual research efforts that typically measured a narrow and single outcome — say, occurrences of moderate NWBs and minor responses. Period. The individual paper studied in the meta-analysis likely didn’t look at the bullied parties and how they chose among minor, moderate and severe responses. It is taking all of these discrete findings and combining them that allow the authors to make more general observations about workplace retaliation.

So, across the data set, a negative behavior deemed to be “minor” on the severity scale was most closely correlated with a minor retaliation (correlation of 0.46), but it was neck and neck with Party B’s striking back with a moderately severe response (0.45), which hints at the notion of responding in a way that escalates. The weakest correlation was Party B’s lashing back against a minor transgression with a severe response (0.32).

When the instigator’s negative behavior was deemed moderate, once again, the strongest correlation appeared for moderate retaliation (0.51): higher than for either a minor (0.28) or severe (0.42) response.

The same pattern generally played out when the initial hit was severe or at other levels of aggression.

In only one set of circumstances did the data suggest a de-escalation in response: When Party A subjected Party B to severe negative behavior, the strongest correlation was when Party B came back with a moderate response. The researchers posit that “individuals may be influenced by strong ethical norms or concerns about legal repercussions that affect viable response options and limit viability of severe negative reciprocation.”

Featured Faculty

-

Jennifer Whitson

Assistant Professor of Management and Organizations

About the Research

Greco, L., Whitson, J.A., O’Boyle, E.H., Wang, C.S., & Kim, J. (2019). An eye for an eye? A meta-analysis of negative reciprocity in organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology. doi: 10.1037/apl0000396