A model juggles who should suffer when a project goes awry; job market prospects of the CEO; and the quality of information shared in the boardroom

Spectacular corporate collapses often have a common denominator — a powerful, ambitious CEO left unchecked by the company’s board of directors. WeWork, Enron and Tyco are prime examples.

Part of the issue is that, in boardrooms, the CEO controls information about potential business projects. They not only have access to all the data but also decide which projects to present to the board. This can lead to skewed presentations, in which the board sees only what looks good and not considerations that might make them uneasy about a project. For some CEOs, this knowledge imbalance enables “empire-building,” a push for investments that boost the CEO’s personal prestige, like building a flashy headquarters or expanding operations, even if those projects don’t benefit the company or its shareholders.

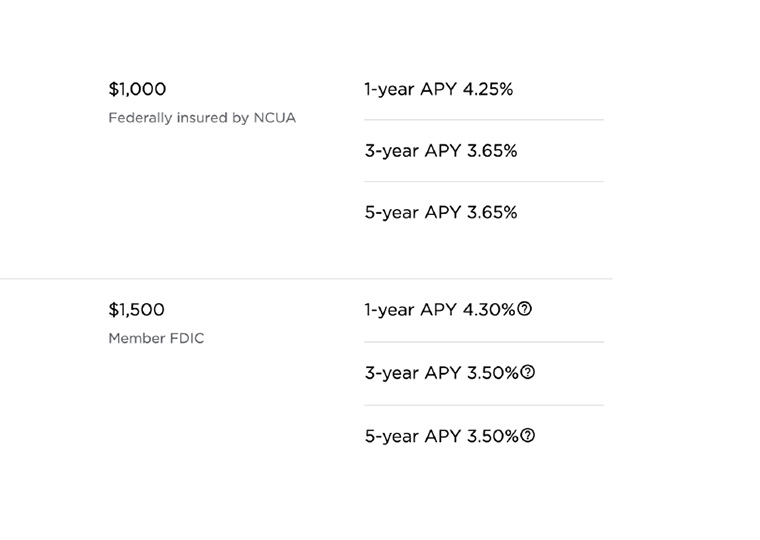

A working paper from Charles University’s Martin Gregor and UCLA Anderson’s Beatrice Michaeli explores how to design a compensation package for a board of directors to encourage better investment decisions and to prevent a CEO from making costly, self-serving choices. The study examines how financial incentives for boards can act as a substitute for direct control over CEOs, improving decision-making. Specifically, the authors analyze how shifting the liability for a company’s investment decisions between CEOs and boards can improve decisions.

“The shareholders’ core contracting decision then can be presented as a decision on which player deserves financial incentives or, equivalently, which player should bear the burden of penalty for failure.”

Gregor and Michaeli developed a theoretical model to examine the interaction between boards and CEOs in investment decisions, focusing on how compensation structures influence these dynamics. In their model, shareholders strategically allocate the liability for a project’s success between CEOs and boards to optimize decision-making. The goal is to ensure that only projects that maximize shareholder profits receive approval. The study explores direct methods, such as adjusting a CEO’s compensation to incentivize better project evaluation, and indirect methods, such as altering the board’s prudence (its threshold for believing in a project’s success) as ways to mitigate overinvestment.

Do Other Companies Want to Hire Away the CEO?

In the studied setting, two regimes emerge. Under the “A-regime,” the CEO’s and board’s interests are aligned. In this scenario, it’s the CEO who faces financial penalties if the project fails, and there is no bonus for successful investments. The board, on the other hand, receives a fixed wage. This setup can lead to perfect information sharing, leading to better investment decisions, but may result in the CEO receiving more compensation than necessary to align their interest with the board. This is due to the need for higher base pay to offset penalties and the loss of other nonfinancial perks.

Under the A-regime, the CEO becomes more risk averse due to the financial penalties that discourage them from taking on projects with a lower probability of success. Shareholders are more likely to choose this regime when a CEO’s outside labor market value is high — meaning they are in demand — allowing the CEO to remain the central decision-maker with a higher compensation to prevent the CEO from being poached by other firms.

The alternative scenario is the “M-regime” where there is misalignment of interests between the CEO and the board. In this regime, the CEO receives a fixed wage, while board members face penalties for project failures. This approach can reduce overall compensation costs for the company by shifting financial incentives to the board. However, it may lead to less efficient information sharing, as the CEO has weaker incentives to provide precise information, leading to suboptimal investment decisions. It can also cause the company to be slower to act and potentially miss out on profitable opportunities.

The researchers suggest that when a CEO is empire-building and their outside job prospects are weak (i.e., other companies aren’t clamoring to hire them away) or when the board members are highly sought after veterans with strong reputations (and will likely want to keep their reputations intact by ensuring prudent investment decisions), the shareholders may find that implementing the M-regime will maximize their returns. This is because the board becomes more cautious and asks tougher questions when making investment approvals. The trade-off is that the shareholders may have to tolerate some overinvestment due to the board receiving less precise information from the CEO. But the company’s compensation costs will be lower.

Trade-offs and Substitutions

The researchers’ model suggests that board and CEO compensation need to be substitutes for one another — if the board takes on more risk (and thus more reward), the CEO’s compensation can be reduced, and vice versa.

As seen, the choices can depend on factors including the CEO’s tendency toward empire-building, the labor market value of both CEOs and board members, nonfinancial incentives for board members like upholding their good reputations, and the potential profitability of projects. The researchers conclude that sometimes it’s actually in the shareholders’ best interest to tolerate some level of inefficiency in investment decisions if it means paying out less in overall compensation.

Featured Faculty

-

Beatrice Michaeli

Associate Professor of Accounting

About the Research

Gregor, M., & Michaeli, B. (2024). Board compensation and investment efficiency. Available at SSRN 4717755.