Output at a Chinese garment factory rose 10%

A recent Gallup survey finds that worker engagement is at an all-time high since tracking began in 2000, yet that number is still pretty poor: Just 4 in 10 workers surveyed reported they are motivated.

The extent to which actively encouraging employees to engage and talk among themselves about their work process and experience — rather than solely listen to the drone of management — might boost engagement is a popular topic of study, and debate.

Lab experiments have resulted in “debates and conflicting findings” among researchers in organizational science, cognitive psychology and social psychology, notes UCLA Anderson’s Sherry Jueyu Wu and Princeton’s Elizabeth Levy Paluck.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

In a working paper, Wu and Paluck move the research beyond the hypothetical in the lab — imagine you’re part of a work group that does X and is subject to the directives of manager/management Y — and onto the floor of a Chinese garment factory, one of the world’s most hierarchical work environments.

Wu and Paluck note that worker engagement is even more foreign in a Chinese textile factory. Not only is non-Western manufacturing predisposed to a rigid top-down management style, there’s a cultural norm, a holdover from Confucianism, that woman are meant to be subservient — and the vast majority of workers at Chinese garment factories are women who typically have not obtained a high school level education.

Wu and Paluck’s experiment tracked more than 1,750 employees assigned to one of 65 work groups at a multinational apparel manufacturing factory in China. The typical workday begins with a 20-minute group meeting in which employees listen dutifully to their manager announce the day’s deliverables for the group and for each individual. Wages are directly tied to production. The more pieces that run through your hands, and the more finished products from your team, the more you’re paid.

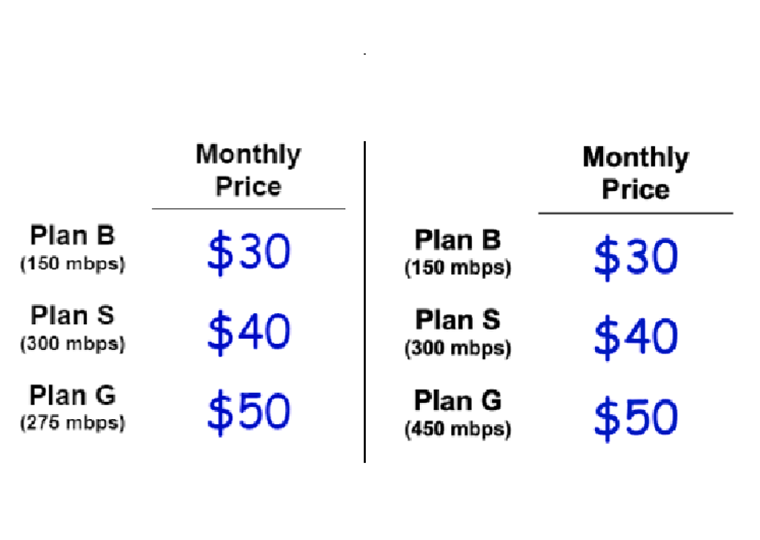

Their results were anything but mixed. Among workers encouraged to speak up, productivity increased more than 10% during the six-week study, and the productivity gains persisted for another nine weeks after the study concluded.

Individuals encouraged to speak up also reported higher levels of job satisfaction and an increased sense of control and well-being than a control group of workers who continued to work under the existing dynamic of following management directives with no worker input. Workers in groups that were encouraged to have a voice also had a higher sense of appreciation of their group and its perceived respect.

Wu and Paluck introduced a novel dynamic for half the work groups: Once a week the supervisor stepped aside — but remained present — and a research assistant trained by Wu and Paluck ran the meeting, guiding the group through a series of prompts that encouraged workers to talk among themselves. Sometimes the focus was on sharing productivity hacks or discussing workflow concerns in the highly collaborative system. (For example, the worker who applies the embroidery to a shirt needs to wait for the colleague assigned to attach the sleeves to the shirt body.) Workers in this test group were also encouraged to share their personal goals.

During and after the study, workers completed detailed surveys that enabled the researchers to tease out what drove the productivity and satisfaction gains. The productivity gains and the heightened job satisfaction weren’t because the workers learned to do their jobs better, but rather, Wu and Paluck determined it was having a chance to speak and, ostensibly, be heard. And it wasn’t necessarily what was said that mattered but the opportunity to speak — period.

A 25% increase in the time workers spent talking about production issues (without any problem-solving) boosted wages for the group the equivalent of $58 USD, relative to no increase for the control group that was not encouraged to talk. Talking about nonproduction issues (say, the quality of the cafeteria food) also moved the needle; Wu and Paluck estimate a 25% pickup in voicing those concerns was responsible for more than a $30 USD weekly wage (productivity) boost.

Given the outsize productivity gains they report — for an intervention that costs little to nothing — it seems reasonable for managers of collaborative teams to consider giving it a go: In periodic meetings, encourage group participation and then sit back.

This study complements other research Wu and Paluck conducted in the same factory that explored the extent to which playing up a cultural norm could drive more productive behavior.

Wu and Paluck are conducting more research to determine if the “voice” intervention, which was so effective in the “nonvoice” construct of Chinese society and Chinese factory norms, would translate to the U.S., where there is less of a societal and institutional imperative to follow the leader.

Featured Faculty

-

Sherry Jueyu Wu

Assistant Professor of Management and Organizations and Behavioral Decision Making

About the Research

Wu, S.J., Paluck, E.L. (2020). Having a voice in your group: Increasing productivity through group participation.