Because they’re harder to get, we assume they’re more potent — and thus preferable over legal ones.

While we may not publicly cop to seeking out illegal products, research published in the Journal of Marketing Research shows we sure find them intriguing. And not only due to the allure of the illicit.

Across eight experiments, University of California-Berkeley’s Rachel Gershon, UCLA Anderson’s Alicea Lieberman and Washington University St. Louis’ Sydney E. Scott build a case that, when given a choice between an illegal and legal version of the same product, we view the illegal product as being more effective than the legal version.

The researchers offer evidence that what seems to be at play is a behavioral bias that presumes a legal product must be less potent than an illegal product because the government allows broad access to it.

They find that when people are explicitly told that a legal product is just as potent as an illegal one — or that its access is restricted, which is the case with prescriptions — the bias decreases. Participants then view the legal and illegal products as equally effective.

The researchers note this insight has immediate practical applications for the public health system. In supplementary research, they identified that 62% of 100 recent drug-related public health information campaigns focused on the danger/risk of drugs. That may be landing on deaf ears, if, as their main research shows, what drives interest in illegal products is the perception they are more effective.

To suss this out, the authors ran a lab experiment with more than 700 college students that tested three different messages around the use of Adderall to boost attention during studying. While Adderall is clinically prescribed as an effective treatment for people with ADHD, it has become a popular black-market study aid even among those with no formal diagnosis.

A control group saw a message that the use of Adderall off-prescription is illegal. Another group got a message about how Adderall can be unsafe when used for nonmedical purposes. And another group got a message that Adderall is an ineffective study aid if you don’t have ADHD.

The message about ineffectiveness reduced participants’ interest in using Adderall relative to the control group. The safety message didn’t. Moreover, there was no meaningful difference in how the three groups perceived Adderall’s safety.

Messages targeting beliefs about a product’s effectiveness, rather than its safety, are a more promising avenue for reducing consumer interest in illegal products, the authors write.

Legal = Weak(er)?

The researchers established a connection between how legal status impacts perception of potency in three experiments that framed products (weight loss drug, teeth whitener and serum to enhance eyelash length) as being legal or illegal. There was a consistent pattern for the legal product being perceived as less effective.

For the weight loss experiment, 900 participants were sorted into three treatments: a control group was told to imagine they had a friend who used a weight loss/muscle enhancement drug for eight months, with no specific legal/illegal framing. The two other groups were explicitly told his drug was either legal or illegal.

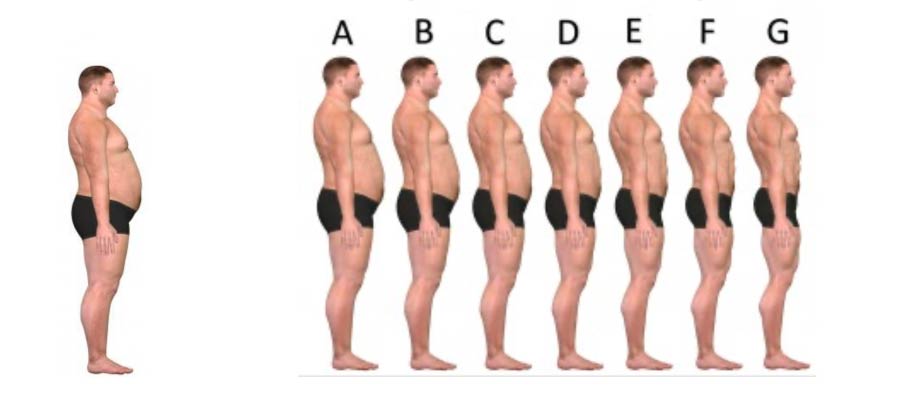

All participants saw a before photo and were told their friend managed to reduce his body fat from 26% to 16% over the eight months using this drug.

Must Be Good

The tell was when all participants were shown seven photos documenting this weight loss journey, and then they were asked to choose the photo that best depicted his end result. This is a visual approach to the 7-point Likert scale (1 least effective, 7 most effective).

Despite the same information, participants who were told the product was illegal rated its effectiveness 4.21 compared with 3.95 for the participants told the drug was legal.

This trend persisted in the teeth whitening and eyelash enhancing tests, as well.

In subsequent experiments the team ruled out that perceptions of safety was the driver (i.e., we think something is less safe, so we intuit it must be trading off safety for potency). What they landed on instead was the impact of accessibility.

There seems to be an implicit belief that the ubiquity of a legal product must mean it is weaker, leading people to think it is both safer and less effective.

To explore this, another experiment used the weight loss scenario again, but this time some participants read that access to the product was strictly limited. When access was seen as equally restricted between legal and illegal versions, there was no difference in perceived effectiveness.

And they offer evidence that this bias may directly impact personal consumer choice. An experiment had 600 participants imagine they were traveling in a foreign country, sprained their ankle and needed a painkiller. They were presented with two choices, both of which were legal in the foreign country. They were told one of the drugs was illegal in the United States. This was to free participants from worrying they were being asked to make a choice in the United States that is clearly illegal. Freed from that potential confound, the control group was simply asked which painkiller they would opt for. The other group was prompted to focus on efficacy: Suppose your top priority is to get the product that most effectively reduces the pain you are experiencing. That is to say, above all else you want a product that will reduce the pain you are experiencing.”

In the control group 11.3% chose the illegal product. But when effectiveness was centered, more than 20% chose the painkiller that is illegal in the U.S.

“We propose that while both products were accessible in this scenario, consumers infer that if the U.S. government has deemed that only one should be accessible (i.e., legal), then it is likely weaker and therefore less effective,” they write.

“There are many factors that consumers take into consideration when selecting health and wellness products (e.g., safety, criminal penalties), but we find that when consumers are particularly interested in a product’s benefits (e.g., when in pain), these inferences may negatively affect their preference for legal products.”

Featured Faculty

-

Alicea Lieberman

Assistant Professor of Marketing

About the Research

Gershon, R., Lieberman, A., & Scott, S.E. (2025). Consumers Believe Legal Products Are Less Effective than Illegal Products. Journal of Marketing.