Research compares U.S. behavior to norms in Asia

Control of the purse strings gives corporate managers a powerful tool to address good and bad behavior. Raises, promotions and bonuses can reward honest actors; withholding those financial incentives sends a message to bad actors.

It’s more complicated down in the trenches. Co-workers lack the ability to wave a financial carrot or stick to signal their pleasure — or not — with colleagues. Yet, as anyone who has worked in an office for more than two days knows, that doesn’t render workers powerless in managing cross-cubicle relationships. Harnessing lessons first experienced on the playground, co-workers can reward or punish through social inclusion and exclusion.

UCLA Anderson’s Jennifer Whitson, Oklahoma State Universityvs Cynthia S. Wang, Joongseo Kim and Alex Scrimpshire and Stony Brook University’s Jiyin Cao set out to explore the extent to which job mobility impacts workers’ social inclusion and exclusion in managing office relationships.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

In a series of three experiments — conducted when Whitson was at the University of Texas at Austin — the researchers studied attitudes of Americans, whose job hopping and career pivots are cultural norms, compared to South Koreans’ attitudes. The average American changes jobs more than twice as often as a South Korean.

The researchers found that the more job mobility people felt they had, the more likely they were to socially exclude dishonest actors.

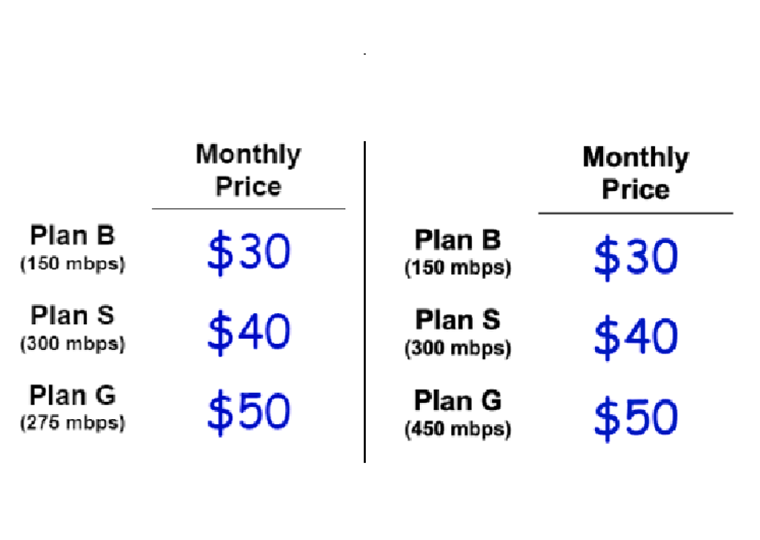

In one experiment, participants were presented with a workplace scenario in which a co-worker’s honesty or dishonesty affected the financial gain of the participant. In the “honest” actor scenario, the participant was told that a $50 reward was being increased to $100, because of the honest behavior of the co-worker. In the dishonest scenario, an expected payment of $150 was reduced to $100 because of the bad actor’s actions. In each case the perceived reward/punishment is the same $50. (Equivalent Korean currency was used for South Korean participants.) Participants were then asked to rate the extent to which they would socially include an honest colleague or socially exclude a dishonest actor.

In terms of including honest colleagues, there was no significant difference among mobile Americans and less-mobile Koreans. But the more peripatetic Americans were demonstrably more willing to punish bad actors with social exclusion. Participants were asked to rate their likelihood of socially excluding a dishonest coworker on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 6 (extremely likely). Americans clocked in with an average score of 4.21, compared to 2.37 for Koreans.

Americans’ greater use of the social sledgehammer, compared with less-mobile South Koreans, sits in contrast to how the cultures use monetary punishment. Echoing prior research from Wang and Angela K-y. Leung of Singapore University, the researchers found that Americans were less focused on imposing financial pain on bad actors. Asked the degree to which they would monetarily punish a dishonest colleague, Americans had an average score of 2.99, compared with 4.35 for Koreans.

As the researchers note, the “contextual affordances of mobility” are at play here. In the more fluid American workplace, we may be less concerned about freezing out a bad-actor colleague because we’re assuming we won’t be colleagues forever. In Korea, where you may be working with that bad actor for a long time, applying a direct monetary punishment may seem more necessary.

“While previous work on reward and punishment behaviors showed that East Asians were more monetarily punitive than Westerners, our results show that Westerners can be just as punitive when utilizing a different form of response.”

For global conglomerates managing across cultures, or anyone posting to a foreign assignment, the research adds an important wrinkle to understanding — and successfully managing — office dynamics.

Featured Faculty

-

Jennifer Whitson

Assistant Professor of Management and Organizations

About the Research

Whitson, J.A., Wang, C.S., Kim, J., Cao, J., & Scrimpshire, A. (2014). Responses to normative and norm-violating behavior: Culture, job mobility, and social inclusion and exclusion. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 129, 24-35. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.08.001