Decade-old bank-risk limits may have exacerbated liquidity problems

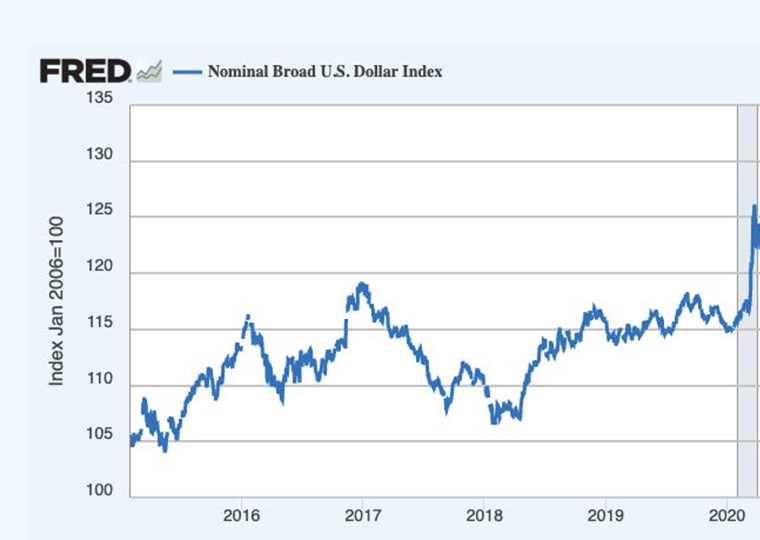

For the second time in 12 years, fears of an economic bust triggered panic selling in March 2020 across U.S. financial markets. Investors’ worries that a pandemic-fueled recession could leave companies unable to repay borrowings threatened the $10 trillion corporate bond market, a critical source of funding for major companies.

What’s more, a meltdown in one financial market can easily spread to others, leading to a broad market crash.

As Wall Street reeled, researchers — Mahyar Kargar of the University of Illinois, Ben Lester of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia and UCLA’s David Lindsay, Shuo Liu, Pierre-Olivier Weill and Diego Zúñiga — saw a rare opportunity to study a huge market in a moment of extraordinary stress. ”All of us have prior knowledge and expertise on the topic of corporate bond market liquidity, and we were interested in learning about it in real time during the COVID-19 crisis,” Weill said in an interview.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

In a working paper, the researchers focus on two main issues. First, to show how illiquid the corporate bond market suddenly became in March, they estimate how trading costs surged for investors who bought or sold bonds during the market’s breakdown. Second, they suggest that the Federal Reserve’s launch of unprecedented programs aimed at boosting confidence in the corporate market helped to quickly restore liquidity.

To measure the cost of trading, Weill and his colleagues bought a listing of corporate bond transactions compiled daily by a databank known as the Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE). It’s made available by the Financial Industry Regulation Authority, or FINRA, the brokerage industry’s self-regulatory agency.

There are two ways for an investor to buy or sell a bond. The fastest way, typically, is to trade directly with a Wall Street bank that buys for or sells from its own bond inventory. This is called a “principal” trade. The bank earns money on the trade by marking the bond price up (to sell it) or down (to buy it), relative to the market price. The difference between the two prices is the “spread.” A wider spread means higher trading costs for the investor.

The second way to trade is via an “agency” transaction, wherein a bank arranges a trade with another investor (say, a mutual fund). Agency trades typically are cheaper to do, because dealers do not need to hold bonds in inventory, but take longer to complete than principal trades.

The researchers found that spreads rose sharply for both types of trades in March, but that banks drove a particularly hard bargain to do principal trades: As pandemic fears initially gripped global markets from March 5 to March 9, the average roundtrip trade spread on corporate bonds in principal trades roughly tripled to about 100 basis points, or 1.0%.

But the worst was yet to come: At the peak of the markets’ panic, from March 16 to 18, the average spread cost of a principal trade briefly surged above 200 basis points. The average cost of agency bond trades also rose in March, but, at its height, still was just a fraction of the cost of principal trades, the study found. The average agency spread cost was about 20 basis points before markets convulsed, and it peaked at just under 40 basis points in mid-March before receding to pre-crisis levels.

Not surprisingly, the high cost of principal trades drove many investors to use lower-cost agency trades to attempt to buy or sell corporate bonds. The number of agency trades as a percentage of all corporate bond trades surged from less than 50% in early March to nearly 65% by mid-March, the study says. But because agency trades usually take more time to complete, their sudden dominance was another indication of an illiquid market.

Changes in bank regulations after the Great Financial Crisis helped set the stage for this year’s corporate bond market upheaval. New federal rules aimed at reducing financial-system risk-taking have caused many banks to limit their holdings of assets such as bonds on their balance sheets. Over the years, that sharply reduced banks’ ability as dealers to participate in principal trades.

That shift away from bank risk-taking intensified as markets staggered. “We find that in mid-March, as selling pressure surged, dealers were wary of accumulating inventory [of bonds] on their balance sheets, perhaps out of concern for violating regulatory requirements,” the study says.

In fact, Weill and his co-authors note, based on FINRA market sentiment data, that “during the most tumultuous period of trading, the dealer sector absorbed, on net, no additional inventory, despite the considerable selling pressure,” the study says. That left it to other investors, such as pension funds and hedge funds, to supply liquidity to the corporate bond market.

And, ultimately, the Federal Reserve, which stepped in with two surprise announcements: On March 17, 2020, the central bank said it would allow banks to borrow against high-quality bonds they own, a move intended to lower the cost of holding the securities. On March 23, the Fed went much further, announcing that it would begin buying investment-grade corporate bonds for its own balance sheet — a historic first. Since March, the Fed has expanded its corporate debt purchases to include certain “junk” bonds. And the Fed’s backstopping even calmed some markets it wasn’t specifically supporting.

While some Wall Street analysts have warned about the “moral hazard” of the Fed’s purchases of corporate bonds, the central bank achieved its goal, Weill and his colleagues write: Soon after the Fed’s March announcements, “Dealers began absorbing [bond] inventory, bid-asked spreads declined, and market liquidity started to improve,” the study says.

The market’s turnabout in late March wasn’t a blip: “Dealers have continued to accumulate inventory through April and the first half of May,” the study says. “Since March 18 the data indicates that dealers have absorbed nearly $50 billion in corporate debt, or roughly double the amount they held before the pandemic.”

Featured Faculty

-

Pierre-Olivier Weill

Professor of Economics

About the Research

Kargar, M., Lester, B., Lindsay, D., Liu, S., Weill, P.-O., & Zúñiga , D. (2020). Corporate bond liquidity during the COVID-19 crisis.