Investors’ future expectations about QE policy lowered long-term yields, made investors feel safer holding the bonds

What if the more debt a government takes on, the safer its investments become? That may sound counterintuitive, but it’s been the reality in the U.S. since 2008.

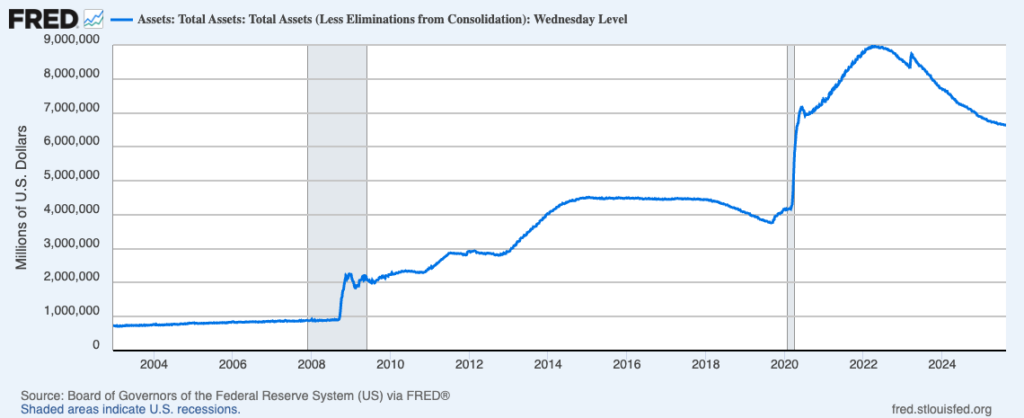

In a working paper, UCLA Anderson’s Valentin Haddad, University of Rochester’s Alan Moreira and UCLA Anderson’s Tyler Muir examine this puzzle. Their analysis suggests that the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing policies have fundamentally changed how bond markets work. QE describes how a central bank purchases long-term government bonds and other securities to pump money into the economy during tough times.

While past economic models viewed QE as emergency one-time interventions, the researchers argue that investors now see QE as a long-term safety net that the Fed will reliably deploy whenever the economy hits rough waters. Unlike traditional models, they model it as an ongoing policy to recognize QE’s persistent impact on the market.

Haddad, Moreira and Muir suggest these ongoing interventions increase the safety of long-term bonds by supporting their prices during downturns. This drives up bond values and lowers yields. They call this the “insurance effect,” arguing it’s been underappreciated compared with QE’s more obvious impact of simply buying up and absorbing the supply of bonds.

The insurance effect makes market participants more willing to take on risk. By making bonds safer, private investors become more willing to buy bonds even when the government issues lots of new debt.

QE’s Universal Impact

Using bond market data from Federal Reserve Economic Data, or FRED, and stock market data from Center for Research in Security Prices,or CRSP, the researchers combined data analysis, event studies and asset price modeling to explore QE’s impact on the markets. They extended their analysis to international markets and international bond market data came from the Jordà-Schularick-Taylor Macrohistory database, supplemented with data from FRED on government bond yields when possible.

Haddad, Moreira and Muir document that before 2008, whenever the government increased its debt burden (measured by debt to GDP weighted by maturity), long-term yields would reliably rise. A 10% increase in this debt measure would typically raise long-term yields by about 12 basis points (0.12 percentage points). The higher yield suggests perceived risk.

After quantitative easing began, this relationship weakened dramatically — and sometimes even reversed.

The authors also examined evidence from 16 countries that adopted QE at different points in time. Controlling for global trends, this staggered implementation of QE allowed them to view its impact on each country. Their work suggests that a country’s yield curve flattened, suggesting lower perceived risks for longer-term bonds, by about 80 basis points after its central banks introduced asset purchases.

Quantifying Future Expectations

When examining specific QE announcement days, the researchers’ data exhibited cumulative yield declines of 100-140 basis points for U.S. 10-year Treasuries; again, lower perceived risk. However, the later QE announcements had much smaller impact, not because QE stopped working, but because markets had already priced in the rule, the authors posit. “The fact that the response to QE policy surprises is muted reveals that the QE policy rule has strongly impacted the bond market.”

Their asset pricing model predicts that QE ultimately lowered 10-year Treasury yields by approximately 115 basis points. This significant reduction stemmed from two main forces: about 75 basis points came from the “insurance effect” — the market’s expectation of future central bank support — and the remaining 40 basis points of yield reduction were attributed to the direct impact of the Fed’s actual bond purchases. The model achieved this separation by analyzing how both the current quantity of bonds bought by the Fed and the market’s anticipation of the central bank’s future support collectively influence bond yields.

Haddad, Moreira and Muir gathered additional evidence from the options markets. When the Fed announced QE-1 in 2008-2009, implied volatility for 10-year Treasury options plummeted by 43%. Meanwhile, options on interest rates a decade into the future fell by 38% to 42%. This dramatic reduction in long-term volatility expectations may provide strong support to the notion that QE created a persistent safety net for bond markets.

Notably, the insurance effect seemed to extend beyond government bonds. Corporate bonds saw yields approximately 50-60 basis points lower for investment-grade debt. Mortgage-backed securities exhibited larger declines of 120-160 basis points, or 1.2-1.6 percentage points.

A Bonus for Tipping the Hand

For the U.S. government, with approximately $36 trillion in debt as of early July 2025, the lower interest rates mean considerable savings. The research suggests that central banks may achieve greater impact by clearly communicating how they’ll respond to future crises rather than focusing solely on current purchases.

The insurance effect of QE may prove more durable — and potentially more powerful — than initially realized, suggesting a fundamental shift in how financial markets operate in the 21st century.

Featured Faculty

-

Valentin Haddad

Associate Professor of Finance

-

Tyler Muir

Associate Professor of Finance

About the Research

Haddad, V., Moreira, A., & Muir, T. (2024). Asset purchase rules: How QE transformed the bond market.