T-Mobile’s $22.1 million disadvantage to AT&T; Arby’s pays more than Burger King

In an age of streaming video services, broadcast television — and the advertising on it — might seems like a relic of the past. Yet for consumer brands, prime-time on the major broadcast networks is still the place to be. Companies are projected to spend nearly $68 billion on TV ads this year, about a quarter of all advertising spending.

When it comes to the cost of advertising, though, not all buyers are treated the same – newcomers typically pay more than longtime advertisers do for the same spot. Industry insiders know these discounts exist, but because prices are closely held trade secrets, their size and extent is unknown.

A new working paper from UCLA Anderson’s Sylvia Hristakeva and Boston College’s Julie Holland Mortimer seeks to shed some light on pricing in this market. Based on data on national ad placements and average ad prices, the authors’ findings suggest, a longtime advertiser will pay about 0.3% less for the same ad spot for each year of seniority over a newcomer.

Newcomers Face Higher Costs to Enter Advertising Market

This can add up: A company that began buying prime-time broadcast ads in 1960 will enjoy a 16% cost advantage over one that entered in 2013. This, the authors conclude, can put young companies at a competitive disadvantage with older ones.

“Legacy pricing may create significant differences in costs between firms competing in the same product market,” the authors write. “Younger firms and new entrants face higher costs to access this input market, which may limit their ability to compete with dominant (legacy) firms.”

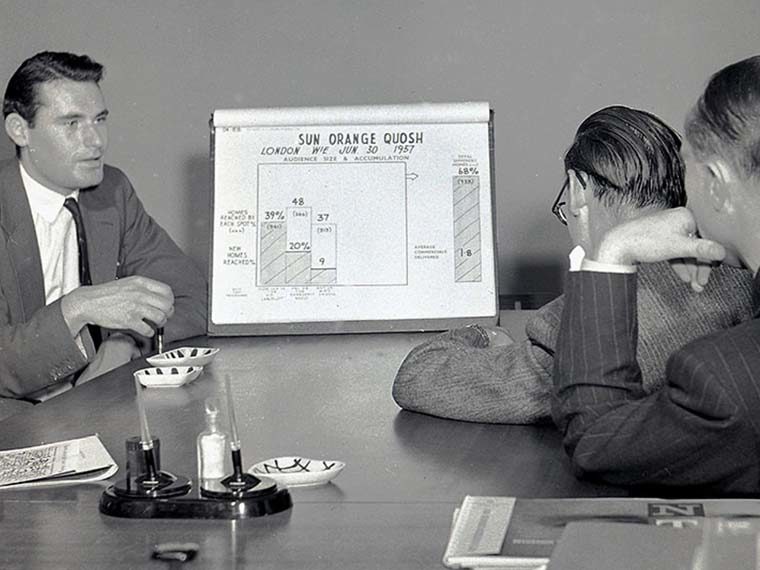

Most advertising on broadcast and cable networks is sold in either the “upfront” or the “scatter” market. The upfront market — established in 1960 by NBC, CBS and ABC — takes place in spring when advertisers negotiate for slots on programs for the fall season. Prices, set in CPMs, or the cost per thousand viewers, vary based on the size and demographics of the target audiences, and the price paid by newcomers is typically higher than those paid by returning ad buyers — an incentive to advertisers to maintain their position in the market.

About 20% of a network’s ad inventory goes into a “scatter” market, where spots are sold close to a program’s air date. Prices here are based on actual demand for a particular ad slot, and few discounts are applied. CPM prices in the scatter market are typically 12% higher than in the upfront market.

Actual prices aren’t published, so computing the size of legacy discounts required tapping into multiple data sources. Data from 23 million cable set-top boxes provided information on program viewership and ad placement in individual telecasts from January 2011 to December 2013. An advertising-analytics company supplied information on the average cost for spots in specific telecasts during the same period, and the authors compiled figures on monthly spending by national advertisers from 1960 to 2017.

The authors took the upfront price paid for all ads in a particular program — for instance ABC’s “Modern Family” on Oct. 16, 2013 — and then matched that with advertisers on the show. Comparing the upfront price — which would reflect any legacy pricing — indirectly quantifies the size of the legacy discount.

From there, it’s possible to see who benefits from discounted ad prices. Say J.C. Penney Co., which entered the upfronts in 1971, and Target, a 1993 entrant, advertised on different shows. Comparing the average prices for ads on the two shows would indicate that J.C. Penney benefits from the larger discount.

The Cost Advantage Is also a Competitive Advantage

A comparison within product categories shows just how valuable these discounts can be.

For instance in telecom, T-Mobile, a 2001 entrant, would save $22.1 million on its annual spending of $180 million if it received the legacy discounts available to AT&T, which has been in the upfront market since 1960. If fast-food restaurant Arby’s, taking part in the upfronts since 2010, received the same discounts as its competitors, it would save $2.2 million on total spending of $22.1 million if it had entered with Wendy’s in 1977 or $3.3 million if it had come in with Burger King in 1960.

These cost differences, the authors say, can make it harder for newcomers to compete with older companies in the same market. And because prices in the upfront market are set for a parent company and cover all its brands, the findings suggest that legacy advertisers are better positioned than smaller independent companies to introduce new brands since a new legacy brand would benefit from the same advertising discounts that its parent receives.

It’s hard to say how significant this competitive advantage is because that largely depends on just how effective advertising might be — something that’s outside of the scope of the study. Still, the cost advantage alone is enough to give some a competitive edge.

“Advertising is an input in production,” Hristakeva says in an email. “Some older firms are able to get this input at a lower price, which puts them in a better position.”

About the Research

Hristakeva, S., Mortimer, J.H. (2021). Price dispersion and legacy discounts in the national television advertising market.