If one company bundles products, its competitors are always better off not bundling; the thing to avoid is a head-to-head competition wherein the only way to get an edge is by cutting prices

On a 1995 roadshow for the soon-to-be-blockbuster Netscape initial public offering, the company’s president and CEO Jim Barksdale met with a group of British investment bankers to sell them on the promise of the Navigator web browser, one of the first to unlock the World Wide Web. One banker wanted to know what would happen if Microsoft, the software powerhouse of the time, decided to bundle a web browser into its product (which it soon did).

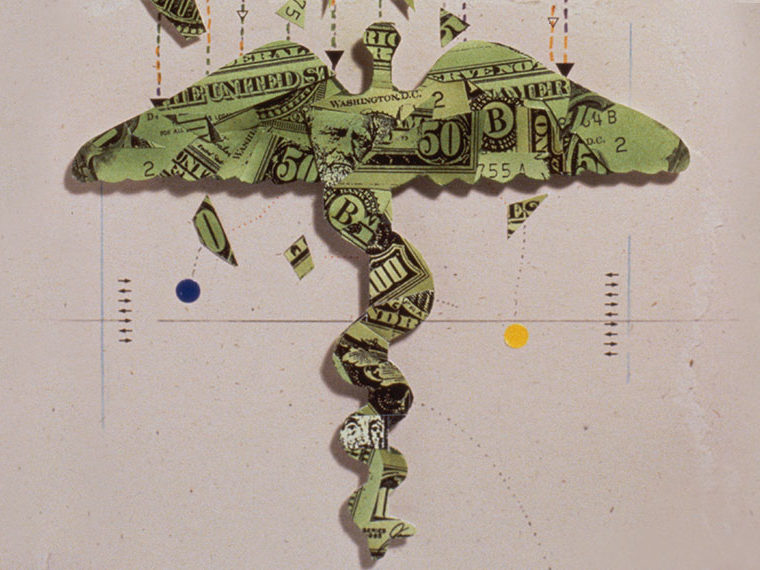

“There’s only two ways I know of to make money,” Barksdale answered. “Bundling and unbundling.”

Bundling — the practice of selling different products in a package, usually for less than if they were sold separately — is a common strategy in a wide variety of industries. Microsoft sells an operating system with multiple applications (still with a browser) and its Office suite of productivity tools. Fast food has the “value meal” combo of a burger, fries and soft drink. Insurance companies give discounts to customers who buy car and homeowners’ policies. Cable operators not only offer packages of channels, such as HBO, ESPN and Nickelodeon, they also sell bundles with cable, internet, phone and home security.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

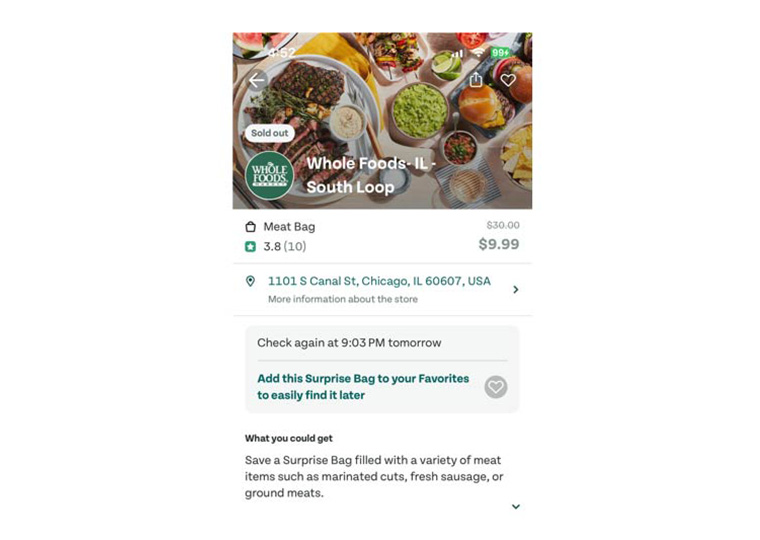

For a while, it appeared bundling might be on the decline. Consumers shifted from CDs to buying individual songs from iTunes. Millions switched to streaming video services and cut the cord to the cable bundle. Lately, though, bundling seems to be back in favor. Disney’s new Disney+ streaming service, for example, sells a discounted package that includes Hulu and ESPN. Buying individual songs has also declined as listeners flock to Spotify and other streaming services for prepackaged playlists.

So it seems Barksdale was right: Bundling can be a successful business strategy, and so can unbundling. The question, then, for businesses is, which strategy to adopt, and when?

A working paper by Bain & Co.’s Araz Khodabakhshian, INSEAD’s Guillaume Roels and UCLA Anderson’s Uday S. Karmarkar gives some guidance. Using a simple model involving two firms that compete on price, they suggest that if one company bundles, the other is always better off not bundling. The reverse is also true; if a company enters a market in which the incumbent doesn’t bundle, the best strategy is to counter with a package of offerings. What’s more, bundling is always the more profitable option. The thing to avoid, the authors conclude, is a head-to-head competition wherein the only way to get an edge is by cutting prices.

“Bundling is essentially used to soften price competition or to create barriers to entry,” the authors conclude. Further, “there are first-mover advantages to bundling.”

Their model also helps understand why there’s such a variety of bundled and unbundled offerings. In actual markets, where companies sell packages and individual products, many competitive approaches can exist in equilibrium, without ruinous price wars.

Bundling offers sellers several advantages. It can provide economies of scale by reducing production, transportation or administrative costs. It’s a way to capture different market segments with a single offering, say, by combining Turner Classic Movies with a sports package. And by bundling lower-value products with higher-value ones, companies can gain more consumer dollars, which is why holiday gift baskets contain lower-cost nuts and crackers as well as premium cheeses and chocolates.

The working paper considers two types of bundling strategy. With “pure” bundling, the company sells its products only as a package, and it isn’t possible to buy individual components; this is how the traditional cable bundle works. With “mixed” bundling, consumers can purchase individual items either separately or together in a discounted package.

With pure bundling, the model suggests, one company always bundles and the other always offers only a single-component product so that neither is forced to compete on price. This explains why online banking newcomers, such as Germany’s N26 or San Francisco-based Chime, typically have fairly narrow offerings, like mobile checking, rather than compete with powerful incumbents’ bundles of checking and savings accounts, credit cards and mortgage loans.

Mixed bundles are more complicated, especially when customers value the pieces differently. Consider two companies with two different, competing entertainment offerings — a sports channel and a movie channel — both of which can sell either channel alone or as a bundle. If, for example, one company offers a full suite of offerings (the bundle and both channels singly), the other company has no easy entry into the business. But if one offers only a bundle, then the other can sell either a sports or a movie channel successfully, but only if it’s a different channel than the one in the other’s bundle.

When customers place a similar value on each of the channels, almost any combination of bundles and single product can lead to a stable market, without price wars. “Hence,” the authors write, “the diverse set of bundling strategies observed in practice can be explained by way of a simple competitive model.”

Featured Faculty

-

Guillaume Roels

Associate Professor of Decisions, Operations, and Technology Management

-

Uday Karmarkar

The Los Angeles Times Professor of Management and Policy; UCLA Distinguished Professor in Decisions, Operations and Technology Management

About the Research

Khodabakhshian, A., Roels, G., & Karmarkar, U. (2019). Competitive bundling in a Bertrand duopoly.