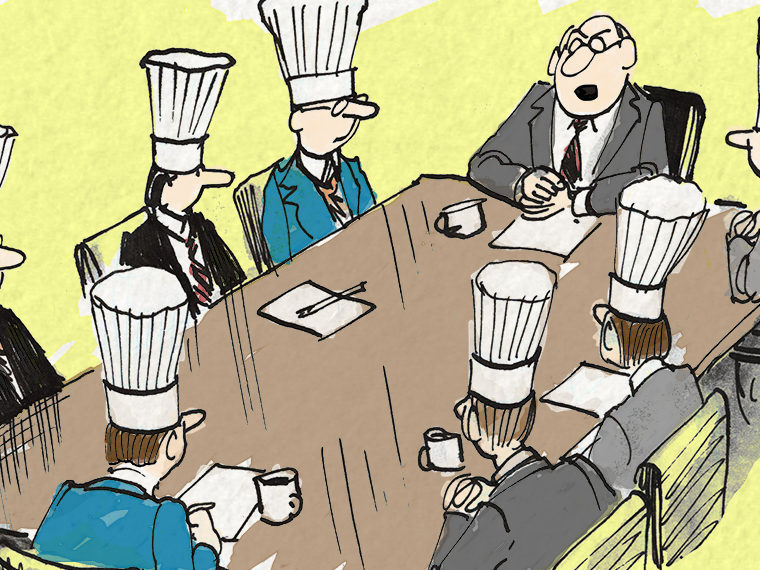

Overlapping tasks among workers well acquainted with each other reduce the need for managers

Citigroup, the New York-based banking giant, announced in October 2023 that it was going to eliminate five layers of management, leaving a mere nine levels of bosses to oversee some 240,000 workers. Out go 60 management committees and some 1,000 internal profit-and-loss reports in the process.

At most very small companies, where employees are few and tasks are also limited in scope, the goal is often to have no managers — only workers (the owner may be among them) who produce something that leads to sales and profit.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

Growth itself might not necessitate adding a manager, but as the number of distinct jobs increases the amount of skills, experience and expertise involved in running a business, the need for management becomes apparent, a study published in Strategic Management Journal explains.

Common Ground Is Key

The paper, by Vanderbilt’s Megan Lawrence and UCLA Anderson’s Christopher Poliquin, using a vast Brazilian database covering 3 million enterprises, suggests that small firms can reduce their need for managers, if:

- Jobs involve overlapping tasks so that employees have more shared knowledge and experience.

- And workers are well acquainted with each other so that sharing knowledge and coordinating efforts come naturally.

These two approaches, of course, fly in the face of much modern management practice, which has advanced extreme specialization of tasks and often leaves workers with little notion of how their job fits into the overall operation.

“Firms whose employees share more common ground — through overlap in their assigned tasks or shared prior experience at a previous employer — are less likely to expand their hierarchy in response to changes in knowledge scope,” the authors write.

Management theory says that coordinating the activities within a growing organization comes at a cost. Companies can mitigate these costs either through impersonal, preestablished rules and formal structures like hierarchy or through personal feedback, such as the mutual adjustments made by co-workers.

To study the decision to add managers, Lawrence and Poliquin used data from the Relação Anual de Informações Sociais, an annual survey of more than 3 million companies in Brazil’s formal economy, and focused on enterprises founded between 2003 and 2014. With the data, which includes wage and occupation information for everyone on a company payroll, they were able to count the number of employees in each firm over time and track their movement from one employer to another. They could also identify the number of unique occupations and the tasks shared by each occupation and see when a company added its first manager.

Do Bigger Firms Need Managers To Succeed?

Getting big enough to have even one manager was rare. In the 12-year study period, only 15% of the firms added a managerial level, either because they didn’t grow or didn’t survive. Because the firms were relatively young, most were small — the median company that survived for five years had only three employees in its fifth year, compared with two after the first year. After 10 years, the median firm had only four employees.

As might be expected, larger firms are more likely to hire managers — one with eight employees is twice as likely to add a manager in a given year as one with two employees.

Those with employees spread across more occupations are roughly 25% more likely to add managers. However, when there is a greater similarity in tasks across occupations, the likelihood of adding a manager is significantly reduced. That’s also the case when more employees share prior work experience.

The study, while limited, has some useful lessons for small, rapidly growing startups. It suggests that they reduce — or at least delay — the need to layer on managers by designing jobs with overlapping tasks, so employees have more shared knowledge and experience. Relying on referrals when hiring can also help, since it’s easier for employees who know each other to work together and coordinate their efforts.

Featured Faculty

-

Christopher Poliquin

Assistant Professor of Strategy

About the Research

Lawrence, M., & Poliquin, C. (2023). The growth of hierarchy in organizations: Managing knowledge scope. Strategic Management Journal, (May), 1–30.