Adjusting for inflation — and, crucially, for taxes — shows bond investors fare better than they might think

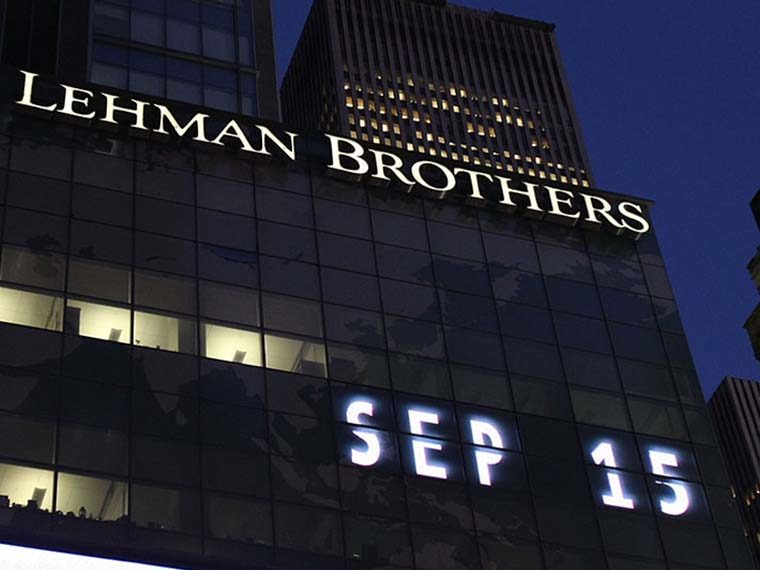

Many income-seeking investors feel like they’ve spent the last nine years wandering in the desert — a yield desert, as interest rates mostly stayed near record lows.

And the recent uptick in rates isn’t much solace. But new research suggests that the interest rate picture after the 2008 financial crisis wasn’t the Sahara that investors came to believe.

The discrepancy is between nominal interest rates (what you’re paid) and real rates, which are what you’ve got left with after both inflation and taxes.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

In a working paper, Daniel R. Feenberg of the National Bureau of Economic Research, Clinton Tepper, a UCLA Anderson Ph.D. student, and UCLA Anderson’s Ivo Welch posit that investors have to take both inflation and taxes into account. And omitting the tax hit significantly distorts true interest returns for many investors, they say.

One challenge in assessing true returns is calculating an average tax rate for bond holders who are subject to taxes (as the study notes, many big investors such as pension funds aren’t taxed). The authors use two methodologies. One looks at a large sample of federal tax returns that disclose key data without revealing taxpayers’ identities. The other approach is to calculate an “implied” tax rate for investors based on the yield difference between taxable Treasury bonds and tax-exempt high-quality municipal bonds.

Using both methodologies, the paper arrives at an average post-World War II tax rate of between 20 percent and 25 percent on bond interest. The authors looked at the nominal yields on 20-year Treasury bonds in that period, subtracted 25 percent for taxes and adjusted for inflation.

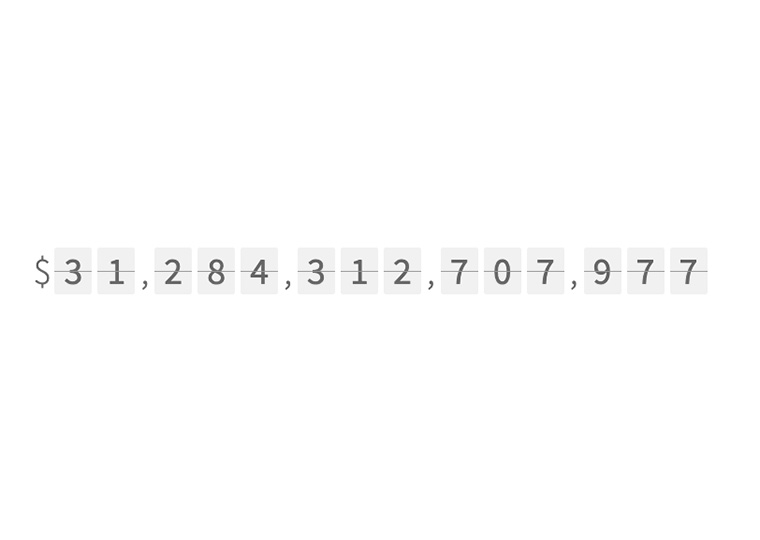

The results: While the nominal average yield on a 20-year T-bond was a mere 2.2 percent in 2016 (down from 5.0 percent in 2006), the after-tax, after-inflation rate earned was nearly 1.0 percent in 2016 compared with just 0.55 percent in 2006.

The 2016 net real return also was above the comparable figures for 1956 (0.8 percent), 1966 (0.9 percent) and 1976 (a negative 1.7 percent), though below the returns in 1986 (2.9 percent) and 1996 (2.4 percent).

All in all, the paper says, “Real interest rates have not been unusually low after the [financial] crisis, when put into the perspective of postwar history.”

The authors make another observation: If real interest returns on bonds haven’t been abnormally paltry since the crisis, and assuming investors are rational, then the popular notion that they fled bonds for stocks and other riskier investments post-2008 “may have been exaggerated.”

That might have been true of “naive investors,” the paper says. But “sophisticated taxable investors should not have reached for yield any more than usual. For them, the ‘real’ short- and long-term interest rates in the wake of the Great Recession should have looked by-and-large mundane,” not absurdly low.

Featured Faculty

-

Ivo Welch

Distinguished Professor of Finance; J. Fred Weston Chair in Finance

About the Research

Feenberg, D., Tepper, C., & Welch, I. (2018). Are interest rates really low?