Technology and “industrialization” are reshaping services as they did manufacturing

These days, as a global pandemic decimates jobs and commerce, many of us can’t wait for the economy to get back to normal. But ”normal” — in the business sense, anyway — has itself been a rapidly changing thing in recent years, and the wide array of economic changes underway seem certain to accelerate rather than slow.

In other words, even when the virus is under control, normal is going to look a lot different than it used to.

That’s one takeaway from a massive examination of the effect on jobs and wages of an economic transformation that falls under the umbrella of service industrialization.

Opt In to the Review Monthly Email Update.

The study by Sam Houston State University’s Hiranya Nath, Uday Apte of the Naval Postgraduate School and UCLA Anderson’s Uday Karmarkar examines 15 years of data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. It reveals how industrialization — resulting from increased automation, the outsourcing of jobs and other changes — has upended the services sector in much the same way it changed manufacturing in the 19th and 20th centuries.

We’re all somewhat familiar with the radical industrialization that has hit manufacturing over the past 50 years. (Those in towns where factories closed might consider it de-industrialization.) Capital, equipment and new processes replaced labor. Many industries went through massive consolidations. Company after company moved to low-wage countries. Specialization became the order of the day. And low transport costs (thank you, shipping containers), along with global communications, allowed the manufacturing sector to build things from far-flung supply networks.

Back to services. We often think of the service sector as more resistant to, say, offshoring of jobs and the automation of tasks. After all, people delivering services historically needed to be close to the people buying them. But that’s no longer entirely the case with the internet, mobile devices and ubiquitous access. Automation has expanded from back rooms to front offices. New online consumer services such as navigation, search and social networking have appeared. Content distribution is being radically disrupted. Self-service, in combination with automation and online access, is taking over many basic transactions.

The labor data the researchers surveyed reveal how the forces of industrialization — the application of capital and technology, re-engineered processes, and a global focus — are all occurring dramatically in services, too, and are poised to accelerate.

They mapped significant job losses in once thriving sales and office-support occupations, along with more recent declines in customer-facing retail jobs. They also tracked the loss of computer processing and other knowledge economy jobs, which saw big increases after World War II, but have since been shipped offshore.

“Perhaps the most serious consequence of service industrialization on jobs is the recent decline of urban white-collar jobs, in terms of both employment share and wage share,” Karmarkar noted in an interview. “This impact will be as serious as — and much more visible than — that which we have already seen with manufacturing jobs.”

Of course, there are jobs in food, hospitality, health care and other physical services that still can’t be easily delivered through virtual interactions. The share of higher-paid management and computer occupations has also increased, along with their share of total wages.

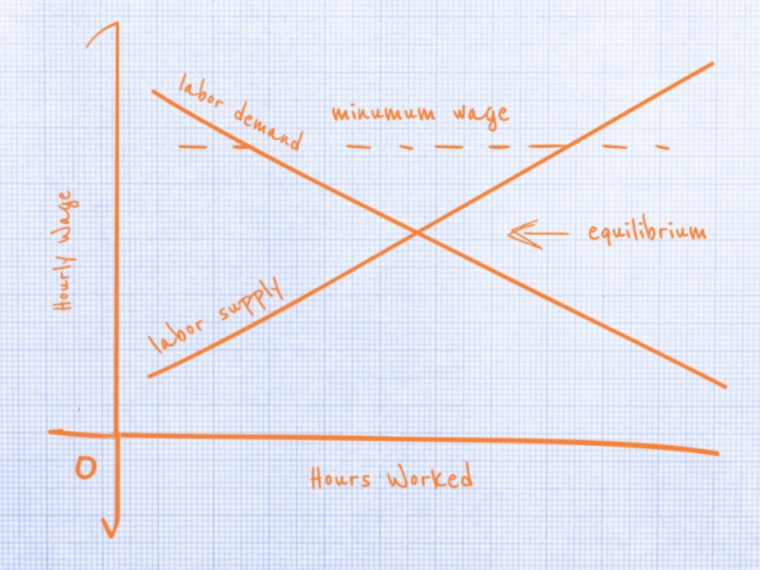

But some of the large and growing job categories don’t pay very well. So the growth of wage share in sectors such as food services, hospitality and personal care does not match the growth in job share. We should also remember that demographic factors, including aging and retirements, are what largely account for the drop in unemployment (prior to COVID-19) and the growth in health care services.

In the U.S., the service sector (which in this tally includes construction jobs) as of 2017 accounted for more than 90% of all jobs after a half-century of growth. The same period saw the expansion of an “information economy” based on computer and communications technologies. The products and services of the information economy make up about 62% of U.S. GNP as of 2017, up from about 46% in 1967.

These new technologies — smaller and more powerful computers, telecommunications and mobile devices connected by the internet — have reshaped the way services are produced and delivered. They have contributed to increased automation (including artificial intelligence), outsourcing and offshoring, greater reliance on self-service and the rise of the “gig” and “sharing” economies.

“This digital transformation of services that is still underway can truly be called a revolution, with a huge impact on jobs, wages, social behavior and income distribution, as well as on the structure of industry sectors, company organization and the nature of work,” said Karmarkar.

In their paper, published in Foundations and Trends in Technology, Information and Operations Management, Nath, Apte and Karmarkar describe employment and wage trends from 2002 to 2017 in 20 different industries and 22 occupations. Examples of notable change:

- Truck drivers. According to the BLS, the trucking industry in 2018 employed nearly two million drivers, and self-driving trucks will threaten a large number of those jobs. Forecasts of just how many vary widely: One report projects that between 2 and 4.4 million trucker jobs in the U.S. and Europe could disappear by 2030, while others see smaller losses. (The BLS, meanwhile, doesn’t mention AVs in its projections; it forecasts a gain of almost 100,000 truck-driving jobs by 2028.)

- Uber drivers, Airbnb hosts and other workers in the so-called gig or sharing economy. Technology-driven, new-economy gig work for such companies as Uber, Lyft, TaskRabbit, Talkspace (for licensed therapists) and Wag (for dog walkers), among many others, has boosted employment for millions of part-time freelance and contract workers. But the effects on wages are mixed. Solid numbers about the size of this sector are hard to come by: In 2017, about 1.6 million people worked in what the BLS calls “electronically mediated employment” — basically, those who get work through apps or websites like Uber or TaskRabbit. While these services have made it easier to find alternative employment, they also can intensify the competition for available jobs, potentially resulting in lower wages. Further, even as these services become more and more popular, increased demand doesn’t necessarily translate into higher income. When more Uber and Lyft drivers enter the market, average wages frequently fall. So does pay for traditional taxi and limo drivers. And that doesn’t take into account the potential loss in pay and jobs once autonomous vehicles come on the road.

- Bank tellers. When pessimists worry about the threat of automation, optimists like to point to this group of finance industry workers. The automatic teller machine, which appeared in the 1970s, was widely expected to make human tellers obsolete. Instead, economic growth and deregulation unleashed the banking industry, which opened more branches and required more, not fewer, tellers. The number of bank teller jobs climbed steadily, from about 300,000 in 1970 to about 600,000 in 2010. But the gains didn’t last. Bank teller employment, the data show, declined by more than 107,000 jobs between 2007 and 2017, and in 2019 numbered about 442,000. The BLS projects the loss of another 57,800 jobs by 2028.

- Office secretaries. Once the Jills-of-all-trades (most were women) in the white-collar office, secretaries prepared and filed documents, answered the phone, maintained their bosses’ calendars and schedules, and handled other administrative tasks. Today, thanks to computers and other technologies, all office staff — including most managers — answer their own phones, create their own documents and manage their own schedules.According to the paper, the number of secretary and administrative assistant positions fell sharply, by 16,000, between 2012 and 2017. While there were still about 3.8 million secretarial and administrative assistant jobs in 2018, the BLS forecasts a further net loss of 276,700 positions by 2028. Executive secretaries account for the largest share of the decline, though medical secretary jobs have increased and are expected to grow further in the next decade.

- Travel agents. Service industrialization also led to a shift to self-service, from mobile banking to airline check-in kiosks and grocery self-checkout. The change had a devastating effect on travel agents. Thanks to online booking sites such as Expedia, travelers search for flights, book hotel rooms and create their itineraries. Between 2007 and 2017, the researchers found, 20,000 travel agent jobs disappeared, leaving fewer than 79,000 in 2018. The BLS projects the loss of another 4,500 jobs by 2028.

These disruptions to jobs and wages will have lasting social and economic consequences, the authors conclude, that in turn will require significant action on the part of government and “socially conscious” managers.

“There appears to be a need for improved policies that can compensate for what the private sector seems to be unable and unmotivated to correct,” they write.

Featured Faculty

-

Uday Karmarkar

The Los Angeles Times Professor of Management and Policy; UCLA Distinguished Professor in Decisions, Operations and Technology Management

About the Research

Nath, H., Apte, U., & Karmarkar, U. (2020). Service industrialization, employment and wages in the U.S. information economy. Foundations and Trends in Technology, Information and Operations Management, 13(4), 250–343. doi: 10.1561/0200000050

Karmarkar, U. (2004). Will you survive the service revolution? Harvard Business Review, 87(6).