Offering higher deposit rates lessens emphasis on loans of fixed rate and longer maturity

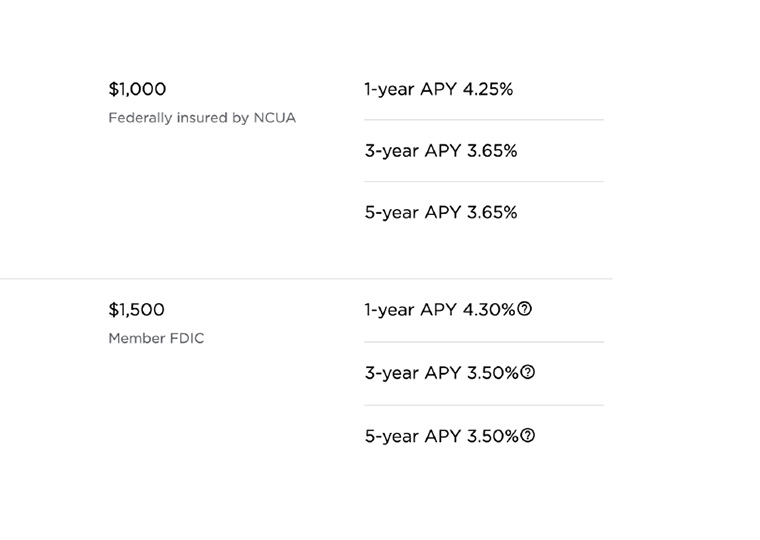

The banking landscape is experiencing a seismic shift: Tech-driven banks are offering dynamic, market-linked rates on deposits, and traditional banks are sticking to lower, fixed-rate deposit accounts. The contrast is exemplified by JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo and Bank of America, which pay almost negligible interest on savings accounts, while PNC, Citi, Marcus and Capital One offer rates averaging more than 4%.

This widening gap is a recent phenomenon, suggests a working paper by UCLA Anderson’s Shohini Kundu, Tyler Muir and Jinyuan Zhang. They demonstrate that banks’ business strategies have been drifting apart over the last two decades, with this divergence notably accelerating since the financial crisis of 2008-09.

Online Banks Are More Competitive?

The driving force behind this transformation is the rise of digital technology. High-deposit-rate banks operate more heavily online with fewer physical branches. They also tend to locate their smaller number of branches in demographically younger ZIP codes, suggesting they have younger customers. Because high-rate banks appear to have lower costs and provide fewer services to depositors, they operate in a more competitive environment and are able to offer higher rates that are closer to market interest rates.

The green shaded area in the graphic below illustrates the portion of the 25 largest banks whose yield on a 12-month certificate of deposit with a face value of at least $10,000 fell within a narrow range of 0.75 to 1.25 times the median rate. Before 2009, there was little disparity in yields, as indicated by the dominance of the green shading. However, since then, the banking sector has witnessed increasing divergence. Banks offering higher rates (blue) have grown, alongside those offering even lower deposit rates (pink). Consequently, the proportion represented by the green shading has diminished.

And that creates diverging deposit activity when rates rise, requiring, Kundu, Muir and Zhang suggest, an altered analytical approach to the industry.

A standard approach when analyzing the state of the banking sector adopts a one-size-fits-all view, treating all banks uniformly. This overlooks the differences between high-rate and low-rate banks, and their respective business models. The common approach has been to aggregate deposits and assets across both types of banks, end of story. Kundu, Muir and Zhang point out that this aggregation misses the flows between the two types of banks.

Tracking where the money is actually flowing within the banking sector is just as important. The two types of banks have vastly differing vulnerabilities to changing monetary policy, the authors note, adding a new element of risk to the financial system. The researchers study data from the 25 largest banks from 2001 through the second quarter of 2023. The gray line in the graphics below track changes in the federal funds rate.

Short-term Versus Longer-term Loans

The implications of the banking industry’s increasingly bifurcated deposit approach are far-reaching. Banks that offer high deposit rates that respond to Fed tightening also run a balance sheet with a shorter-term focus. Rather than the old-school traditional bank strategy of using lower rate deposits as the foundation for making higher-rate, longer-term loans, high-rate banks seem to manage the risk of paying higher deposit rates to less loyal customers by focusing on shorter-term assets and lending.

Kundu, Muir and Zhang also offer evidence that concurrent with the rise in predominantly high-rate banks offering higher deposit yields, traditional banks have doubled-down on their business model. They document that low-rate banks have effectively chosen to not compete with high-rate banks — they have in fact offered even lower yields than in the past — and have extended the average maturity of their assets, which include loans, bonds and such.

The end of the Fed’s zero-rate policy that began in full in 2022 presents an important juncture for the banking industry that brings this bifurcation in business models front and center. Though the Fed managed to move its target federal funds rate up to 2.4% between late 2015 and 2019, this is the first time since the financial crisis, when high-rate banks were still in their infancy, that the rate has been above 5%.

Kundu, Muir and Zhang make a case that the deposit pressure on low-rate traditional banks when the Fed tightens has implications for the important industry function of “maturity transformation,” which is banker speak for paying lower rates on short-term deposits and then turning around and lending out money longer-term that earns a higher rate.

“Deposits shift substantially towards high-rate banks when interest rates rise and reduce the ability of the banking sector to engage in maturity transformation,” they write. Maturity transformation — accepting deposits of a maturity customers prefer and also lending at maturities customers prefer, and managing the risk of that complex function — is among the crucial middleman roles played by commercial banks in the economy.

High-Rate Banks Offset Short-Term Balance Sheet Focus With More Credit Risk

Because high-rate-seeking customers are more flighty than traditional bank customers who accept lower deposit rates in return for valued services, high-rate banks need to manage liquidity risk. Kundu, Muir and Zhang show that translates into high-rate banks holding more short-term investments and focusing more on short-term lending than traditional banks. Short-term loans include business loans — known as commercial and industrial credits, which often re-price as interest rates move — and consumer loans, such as car and credit card loans. By contrast, low-rate banks focus on holding long-term securities, including Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities.

This perspective also sheds light on why a significant credit crunch has yet to materialize despite aggressive Fed rate hikes begun in 2022. As the Fed pushed up rates from roughly 0% to 5.3%, aggregate bank deposits declined by more than 8% — the largest in percentage terms since the data began in 1973.

This caused disruptions in the banking sector, including the failure of several large banks. According to standard theories on the transmission of monetary policy, a dramatic decrease in deposits would usually lead to a credit crunch. But a credit crunch hasn’t materialized.

Why? The authors suggest it’s because the deposit outflow was concentrated among low-rate banks. They, in turn, reduced their holdings of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities. In contrast, highrate banks experienced negligible deposit outflows, and lending — to both consumers businesses — hasn’t been significantly curtailed.

The researchers calculate that between early 2012 and May 2023 asset growth was 20% higher for high-rate banks than low-rate banks. They apply that differential to conduct some “back of the envelope” calculations on the net effect of these different business models for the overall industry. They suggest that if 10% of deposits shift from low-rate banks to high-rate banks, the banking sector as a whole originates, approximately, loans with 5% shorter maturity and assumes 20% more credit risk. Such a shift potentially increases the concentration of credit risk within the banking sector while limiting its ability to provide long-term financing for infrastructure and mortgages.

Prior to the financial crisis, there was no meaningful difference in the credit spread — roughly, the difference between interest paid out on deposits and interest received on loans and other assets — of high-rate and low-rate banks. By May 2023, however, the difference was more than 2 percentage points.

The researchers calculate this translates to an estimated 11% increase in sector-wide credit risk compared with pre-crisis. They also note that the charge-off rate (percentage of loans written off as a loss) in mid-2023 for high-rate banks was more than double that of low-rate banks.

Despite the diverging risk, the researchers show that there are no significant differences in the regulatory capital between high- and low-rate banks, suggesting that existing regulatory capital practices may not fully account for differential risks within the banking sector. This has implications for systemic risk evaluation and the formulation of overall economic policies and monetary interventions.

“Understanding the distribution of deposits across high- and low-rate banks is important for a comprehensive understanding of the deposit and lending channels of monetary policy, beyond tracking total deposits in the banking sector,” they write.

Featured Faculty

-

Shohini Kundu

Assistant Professor of Finance

-

Tyler Muir

Associate Professor of Finance

-

Jinyuan Zhang

Assistant Professor of Finance

About the Research

Kundu, S., Muir, T., & Zhang, J. (2024). Diverging Banking Sector: New Facts and Macro Implications.